Nikola Tesla is one of the most fascinating inventors and futurists in recent history. His numerous accomplishments include the AC induction motor, Tesla coil and radio communication. His method for creating and inventing was not conventional – he relied heavily on imagination and visualized his ideas in great detail before taking any action on them. He describes his thought process as:

“I do not rush into actual work. When I get an idea I start at once building it up in my imagination. I change the construction, make improvements and operate the device in my mind. It is absolutely immaterial to me whether I run my turbine in thought or test it in my shop. I even note if it is out of balance. There is no difference whatever, the results are the same. In this way I am able to rapidly develop and perfect a conception without touching anything.”

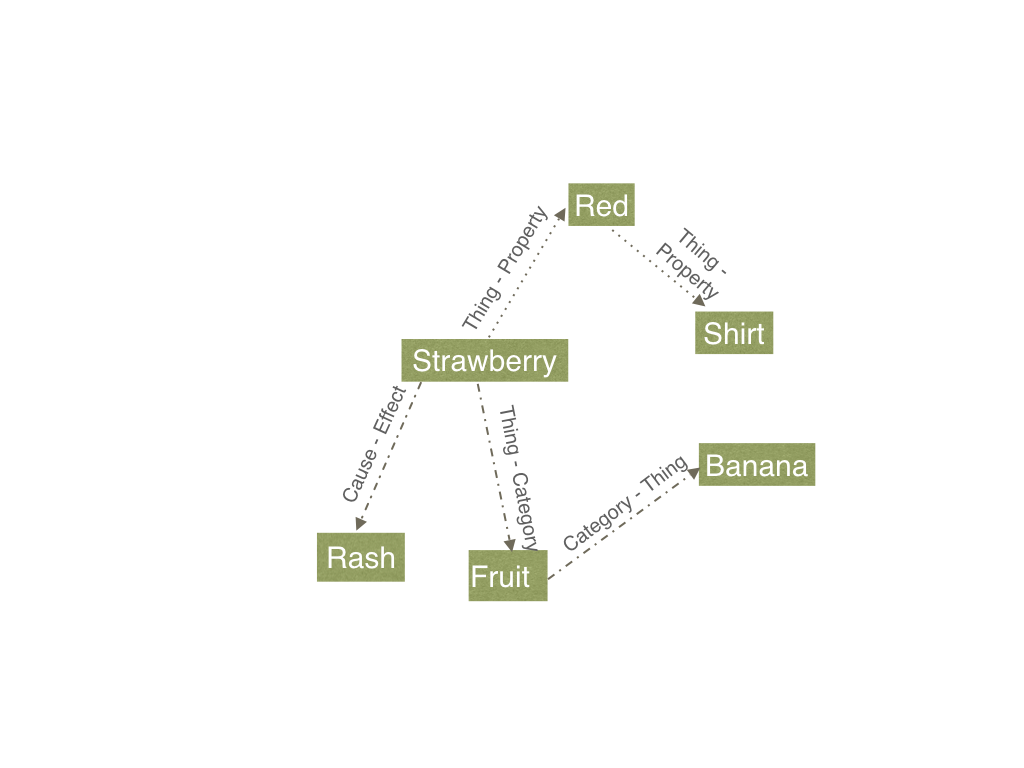

Imagination is the ability to form internal images of objects or situations that are not present to the senses. It is often the first step for a creative endeavor, and often provides the initial insights that lead to a novel solution. Tesla’s ability to visualize and imagine complete devices was extraordinary and allowed him to save immense amounts of time typically spent in prototyping. This approach to imagining problems and possible solutions has been common to many creative endeavors and scientists like Einstein, Feynman and many others have described their own imaginative experiences that led to scientific breakthroughs.

There are other aspects of imagination that go beyond conceiving a single creative idea to building a more holistic creative mindset for an individual.

From the earliest ages, children engage in pretend play with each other and with their toys. They imagine themselves in new roles and new situations, which helps them build crucial social and problem solving skills.

When older students can imagine a future self that is more successful than their current selves, they are more likely to regulate their current behavior and show more persistence. They are more likely to participate in class discussions, spend more time in homework and achieve better grades.

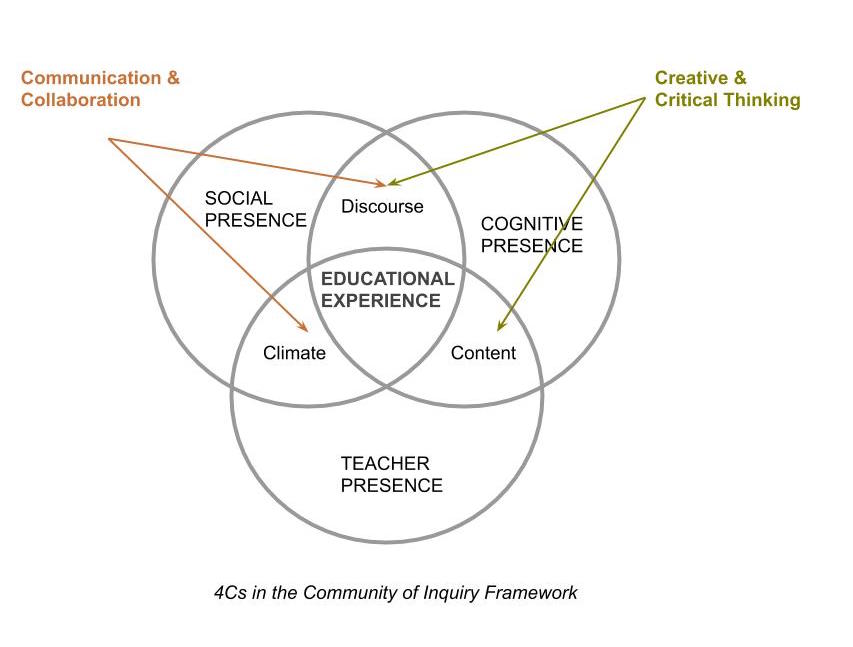

Imagination’s benefits go beyond personal goals to more broader social contexts. Similar to pretend play, when students are able to imagine others’ perspectives and their feelings, they are more effectively able to build consensus and navigate tricky social situations.

Despite the advantages of nurturing imagination and creativity, our educational system currently doesn’t prioritize building these skills adequately. As researchers in imagination point out, “…supporting youths’ capacities for social-emotional imagination – their abilities to creatively conjure alternative perspectives, emotional feelings, courses of action, and outcomes for oneself and others in the short- and long-term future – is a critical missing piece in many classrooms.”

While imagination is often considered a “soft-skill” and therefore less important than critical thinking, it is really a cognitive skill that schools should encourage in students. Imagination helps not just in creative problem solving, it also helps build important social and emotional skills that are essential for success in the real world.