The story of how the sticky note became a huge market success is a story of ingenuity and persistence. It’s also a story that exemplifies why disruptive ideas are so hard to manage inside a company.

In 1968, Spencer Silver, a scientist at 3M, was working on making a super-strong adhesive but accidentally ended up creating a weak adhesive that could be peeled off easily and was reusable. Intrigued by the new material, Silver tried to get support within the company to find ways to commercialize it. Over the next five years, he gave seminars to different groups and talked to many leaders in the hope that it would spark new ideas. The most promising idea a product group came up with was a reusable bulletin board that people could stick paper to but that idea was abandoned because bulletin board sales are not large enough to make this a profitable business. Without any good commercially viable use case, Silver couldn’t garner any support for his new adhesive. That changed in 1974 when Art Fry, another colleague at 3M who had attended one of Silver’s seminars, came up with an idea to use the adhesive on pieces of paper to act as bookmarks for his hymn book. Fry then tested the idea within the company some more. He sent a report to his manager with a sticky note on top, who then responded back on the same note. Soon other employees started using it and 3M decided to take the idea more seriously. They did a limited launch of the sticky note in four cities but it failed to generate much sales. Fortunately, they realized that the launch failed because the concept was new and customers were not able to gauge how useful the sticky notes would be. So, they did one final test in Boise, Idaho, where they handed out free sticky notes to businesses and waited to see the response. Over 90% of businesses ordered the sticky notes when they ran out giving 3M a very clear signal of success!

Despite the skepticism they received, Silver and Fry’s persistence paid off eventually and led to a category defining product for 3M. But their story illustrates why it’s so hard for companies to identify and grow disruptive ideas.

Companies are optimized for incremental innovation

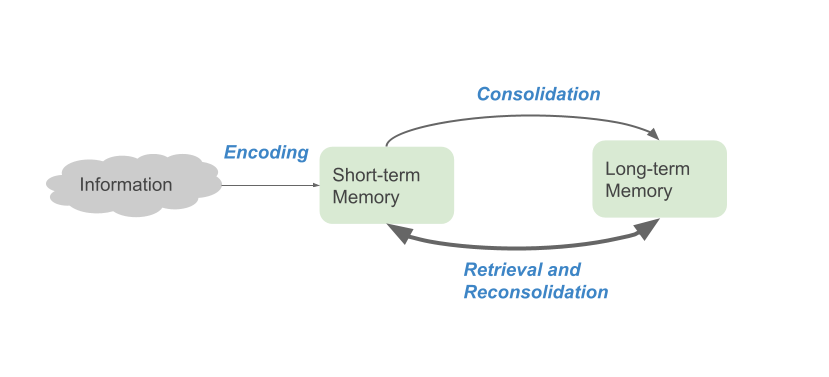

Most companies have a dominant thinking style that favors short-term incremental innovation. Consider how new features get incorporated into a product. In most places, there is a well established protocol starting with user studies to identify how the product might be made more efficient or intuitive. However, this approach can only result in incremental innovation. Imagine you were a leader at 3M faced with evaluating Silver’s discovery. You would most likely ask the same (logical) questions like what pain point or unmet need of the customer gets addressed by the new idea. And you would end up rejecting the idea in the first meeting. Unfortunately, they are the wrong kind of questions to ask for disruptive innovation when you are creating a new product category.

In the case of 3M, even the marketing team fell victim to established thinking and only after recognizing that people can only evaluate a product once they are familiar with it, did they hit success.

The issue here isn’t that managers are not capable of identifying good ideas or that they let their egos get the better of them, but instead, as researchers found, “…managers face two distinct hurdles: They are not empowered to act on input from below, and they feel compelled to adopt a short-term outlook to work.”

Handling Disruptive Ideas

To manage disruptive ideas, companies need to create a different channel where radical ideas can survive, and the most recommended approach is to create a different team to incubate such ideas. However, this approach still requires managers and employees to understand radical ideas so they can be fed into the new channel. Without this step, the incubating team starves for good ideas coming from product teams that can potentially be successful.

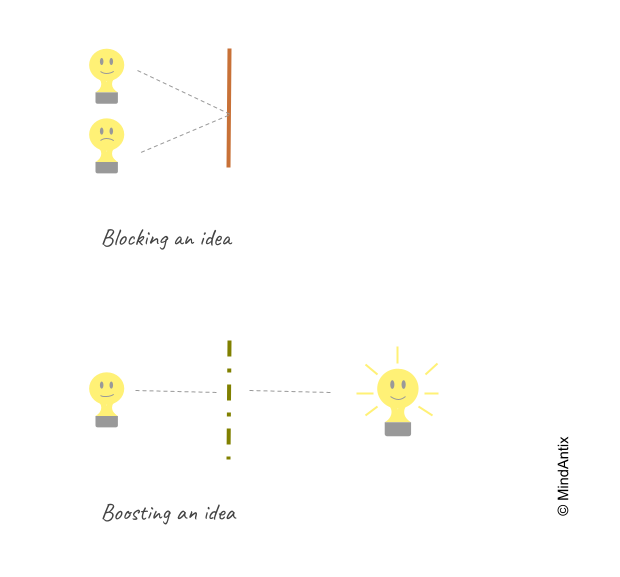

Boost ideas before evaluating them

Transformational ideas don’t always sound convincing or practical in the beginning. One mistake leaders tend to make is to focus on evaluating the idea when they first hear it. This works well in the case of incremental innovation where the value proposition is easy to understand – whether it is improving performance or making the design more intuitive. As a result they end up blocking ideas too early. For transformational ideas, it helps instead to first understand the full potential of an idea before starting to evaluate it. This requires looking at an idea from multiple angles, finding new use cases or connecting with other products that the person proposing the idea may not have thought through.

Leaders need to create an exploratory phase where ideas can be built up in different ways to see their full long-term potential. Most radical ideas tend to get blocked early on but by adding a boosting phase, companies can significantly increase the number of potentially disruptive ideas they see.

Idea evaluation shouldn’t be the manager’s job

Managers are often the first hurdle that an innovative idea has to cross. If a manager gets convinced that an idea has merit, then they can champion the idea further up the chain. This works quite well for incremental innovation, where a manager’s experience can play a meaningful role in evaluating and shaping the idea more. However, for radical ideas, the same strength becomes a weakness. Like in the case of the sticky note, where a colleague from another part of the company was able to identify the potential of the adhesive, evaluating ideas should be a broader effort. When it comes to creativity, no one person is going to consistently pick winners but by including more people in the mix, companies can start tapping group intelligence towards innovation.

Leaders should recognize when an employee is bringing a radical idea, and push it through a boosting stage. In the simplest form, managers can bring the team together to brainstorm on the idea with the intent of finding the most promising incarnation.

Remove individualistic biases

Most companies disproportionately reward the person who “first came up with the idea”. The reality is that most ideas in the initial formulation are weak and it often requires significant contributions from many others before an idea can fly. When incentives are misaligned, employees might choose to propose their own idea instead of helping other ideas become successful. As a result, instead of one or two killer ideas, companies are left with multiple mediocre ones.

To combat individualistic tendencies, leaders should set expectations with the team that ideas become groundbreaking through many people’s contributions and routinely reward people who help others’ ideas become more successful.

As AI becomes more prevalent in society, businesses will need to innovate at a faster rate than ever before to stay competitive. Companies that figure out the formula to churn out disruptive ideas will have a big edge over others. This requires companies to understand ways in which disruptive innovation differs from incremental innovation and reengineer incentives and processes to support transformative ideas from employees.