Scientists have always been interested in how the brain works and how specific parts of the brain aid in specific tasks or behaviors. One of the earliest people in this domain, Franz Gall, developed his keen interest of observing his classmates’ skull sizes and features into the field of Phrenology. While phrenology is now debunked as pseudoscience, advances in brain scanning technologies have led to a much improved understanding of the brain, and the birth of cognitive neuroscience.

Recent work by cognitive neuroscientists in the field of creative thinking has shown that some of our earlier beliefs about the right and left parts of the brain are not exactly correct.

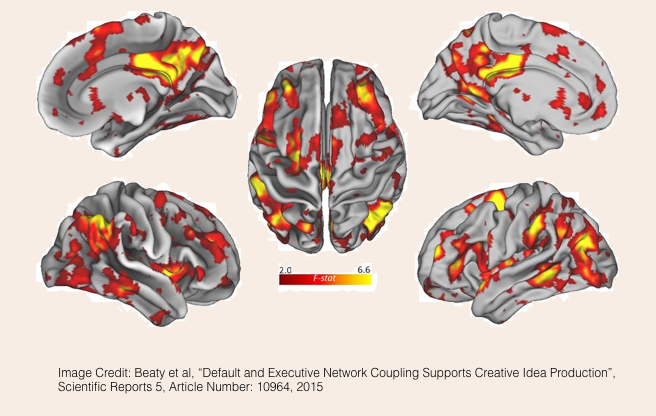

In one study, researchers split participants in high creative group and a low creative group based on their performance in the Creative Functioning Test. They then gave the two groups tasks for fluency (FAS – list as many words starting with the letters ‘F’, ‘A’ or ‘S’) and divergent thinking (DT – list as many uses of a brick). They found that the high creatives used prefrontal regions on both hemispheres on the brick task compared to the low creatives who mostly used regions in the left hemisphere.

In another study, researchers gave the Unusual Uses task from the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT) to two groups – one that scored in the 99th percentile on the TTCT and the other that scored 50th percentile. The 99th percentile group showed elevated activation of both the right and left hemispheres during the task (although the activation was higher for the right hemisphere).

So one key takeaway from these and other studies is that creative problem solving recruits both sides of the brain. As psychologist, Keith Sawyer concludes, “there is no evidence for the popular belief that creativity is located in the right hemisphere of the brain. Many regions of the brain, in both hemispheres, are active during creative tasks.”

One reason that both hemispheres show activation during divergent thinking (DT) is that semantic memory is primarily stored in left hemisphere. However, these semantic memory traces most likely include primary associations. So when a user thinks of different uses for a brick, the first set of responses come from these primary associations and which lead to more common responses. To come up with more original ideas, secondary associations need to be tapped and these are more likely to be in the right hemisphere. Given this theory, the classic brainstorming advice of going past the initial set of ideas to get to more original ideas makes more sense. Once the initial set of ideas that use primary associations are exhausted, the second wave of ideas start recruiting structures from the right hemisphere more.

A better way to think about creative cognition is not in terms of the left-brain right-brain dichotomy, but as distributed networks in the brain that span both hemispheres.

Professor Scott Barry Kaufman lists three large scale networks that play a crucial part in creative cognition:

-

- The Executive Network: The Executive Network gets involved in tasks that require focused attention, that place demands on working memory, like solving a tricky math problem.

- The Imagination Network: The Imagination Network, also known as the Default network, is associated with spontaneous and self-generated thought that includes mind wandering and social cognition.

- The Salience Network: The Salience Network monitors both external stimuli and internal stream of thought, and flexibly switches between the two as needed.

Advances made in cognitive neuroscience are helping us understand how the cooperation between these three networks leads to more creative thought. It has now become evident that the right side of our brain isn’t just an intuitive center – it plays a critical role in creative and complex problem solving!