By Boris Serebro

(This is a guest post, contributed by one of our parents who collaborated with us to bring the “How To Be An Inventor” program in his school. Boris, not only championed to bring this in his school, he helped translate the material, coordinated with other parents, and found ways to enhance the program! It was truly a joy working with him and we are grateful for that.)

I think most of us already know that creativity and innovation are major contributors to today’s changes in the world, but not a single one of them is taught in schools. I was looking for ways to improve and freshen up the way my children learn, in order to prepare them better for a successful career and grown-up life. I happened to stumble upon a publication about this wonderful idea of “creativity is something that can be taught”, and saw the “How To Be An Inventor” course, and it fit like a glove!

The school my kids learn in, Nitzaney Ha Mada, has earned itself a reputation of a fresh and open-minded school over the last years, mainly due to the amazing work of the school director, Dorit Nadler, and her pedagogic team. They are working hard on inventing new ways to help the students reach newer heights, by bringing extracurricular activities and programs, such as adopting a new teaching method of positive thinking and speaking the happiness language as a way of promoting personal excellence in students, and making the novel concept of “school without homework” a working example for other schools.

So all I had to do is stitch the various pieces together. I first met with Pronita, the MindAntix founder and CEO and got her agreement. My spouse and I then met with Dorit and got her excited blessing and agreement of cooperation from the pedagogic team. Since the current staff was very busy with its own curriculum and extracurricular activities, and the fact that the material is in English, we had to gather a group of volunteering parents to teach in each of the four 4th grade classes. For all that to run smoothly, I also had to translate the material before each lesson.

Creativity Skills

The course is structured in a way that for almost half the duration students focus on learning different creativity techniques that can help them come up with interesting ideas for their inventions. Only after spending enough time with ideation, do students pick the most promising one to take further as their final invention.

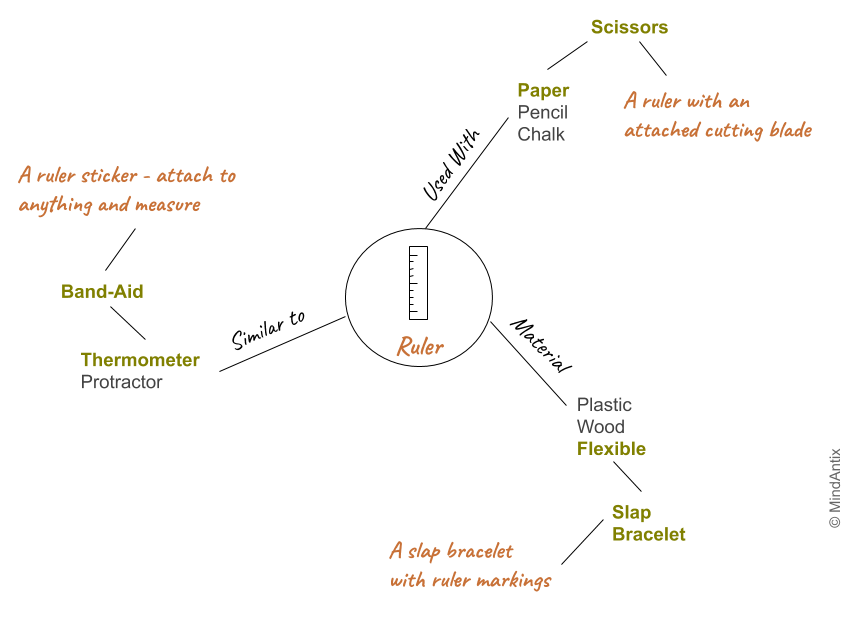

Some of the creative thinking techniques that students learned were:

- Association Map: How to use combine concepts that were one or more hops away to find product ideas that were surprising.

- Using Random Associations: How to combine unrelated ideas to get original and interesting ideas.

- Challenging Assumptions: How to look out for hidden assumptions and reverse them to get new insights and ideas.

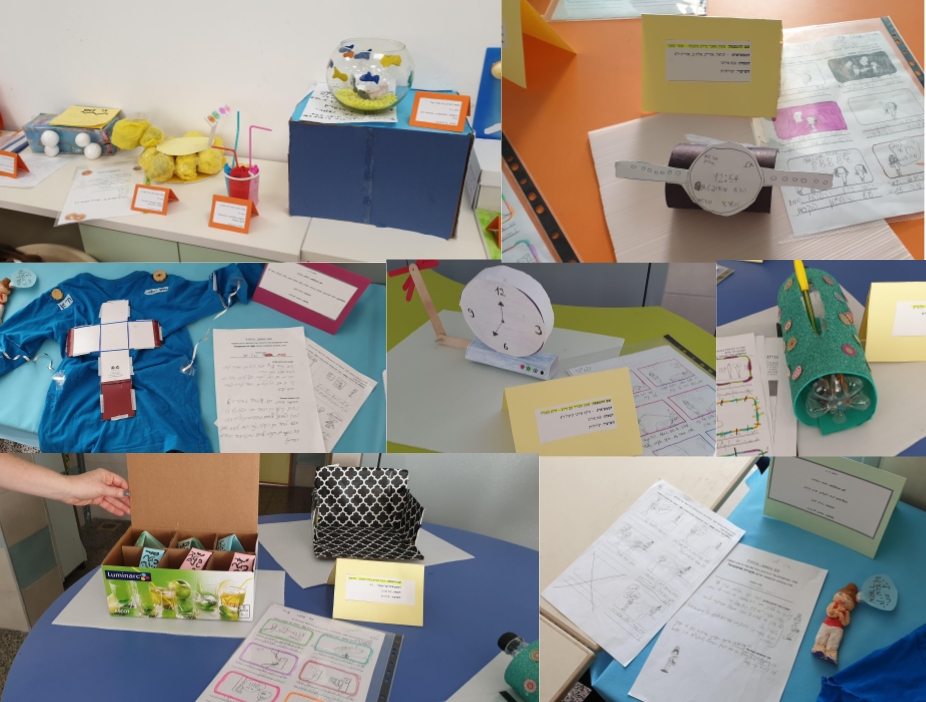

Student Inventions

By the end of the course students had come up with many interesting ideas for their inventions and were excited to showcase them. Below is a small sampling of some of the neat ideas from the students:

- A Scented Book: It’s a book that also comes with the smells of the story and upgrades the experience of reading a book. It was originally a book with lemon/orange smell to help to cope with nausea during bus rides, but the idea evolved over time.

- Rubber Duck Vacuum: A rubber duck-shaped vacuum, to be operated by small children to help their parents. While kids play with it, it vacuums and cleans the house.

- Seasonal shirt: A self-folding/ collapsible (into a small box, that can fit in a pocket) sweater for those times when the weather changes and you’re too hot / too cold.

- Climate control doll:The doll would detect the weather by itself and will operate its hands like a fan to cool you and even add some water splashes out of its mouth, to help you cool.

- Juice box: A single bottle with internal compartments that allow you to store more than one type of drink, be able to drink and mix and bring it all with you on a trip.

- An effective wake-up clock: A clock with an arm, which is set to be activated after some time the user does not wake up (the inventor has difficulties waking up in the morning).

- Smart closet: The closet is operated by voice commands, opens up and brings you the clothes you need with a telescopic hand.

- Airplane book stand: A retractable stand to help with holding an open book for reading, without the use of hands. The original intention was to help with nausea, but is also helpful in times when food is served or busy hands.

Overall Experience

The course material is very organized and contains very detailed instructions on what to teach, how to say it, how to present the examples and even how much time each part should take. So, as the teacher-parents we had confidence and a very good starting point to prepare for the lesson.

The course itself takes a methodical approach on how to teach children to be inventors. The course teaches the kids a few tools and methods to come up with new ideas. The kids were excited to learn those new methods and play with them.

We enhanced these activities by bringing real-life examples of useful and funny inventions, to inspire the children and engage them in thinking. We also added additional examples to the course material, in order to let the children practice together before approaching the course exercises, so that they would grasp the ideas better. This was really important, as the children from various levels sit together in the same class. This was a method to bring them all closer to a more or less equal start. Another purpose of those examples was to better and graphically explain the concepts to the kids, who are used to learning from screens and powerpoint presentations.

Some sessions took us longer than expected, despite us separating them into working groups. Some times when the students had difficulty grasping a concept, we had to adjust our pace, reinvent examples and modify methodologies (like do class reviews on peer work so that other kids would get inspired).

Later on, the course continued to show students the process of turning their creative ideas into reality. The kids got to learn about the process inventors go through, which is something we learn today only in universities, if at all.

Since some of the material was less relevant for us (for instance, our students didn’t have computers in the class to work on their online assignment), we decided to add our own material and went deeper with them on the process entrepreneurs go through. We added modern subjects such as crowdfunding, together with real-life examples of actual products that started there and became a reality.

The feedback we got from the parents and the children were amazing. First, the children would eagerly wait for this weekly lesson. The lessons are interactive, and almost all of them have some game that involves the whole class. Since this was a totally new and different material, alongside games, this added to the excitement in the class. Second, the parents told us that “their kids always shared with them the new things they learned in the course”, and were amazed by the content and how interesting this program is.

In the end, we felt that the students learned at a much deeper level what it takes to be an inventor and had fun along the way.