As we start the new decade and move towards the post-pandemic phase with cautious optimism, the question of how education needs to evolve is still looming. The pandemic shone a light on challenges like the magnitude of inequity in our society, but it also became a catalyst for better technology adoption in schools. Without technology platforms that made remote learning feasible, it is scary to imagine what last year could have looked like.

However, the role technology has played in education so far has been to enable the same teaching that took place in person to occur in remote settings – it hasn’t really transformed education in deeper ways. But transformation is what’s really needed to address underlying issues.

The problem with our current educational system has been in the making for several decades – we are simply not adapting fast enough to keep up with the technological progress. The gap between skills that students acquire in schools and skills that are needed in the workforce continues to widen.

Jonathan Rochelle, who started the Google Apps for Education team, captured the essence of the problem we face in education today. While comparing the progress we have made in machine learning to human learning, he quipped “we are teaching machines to be more like humans and we are teaching humans to be more like machines.”

Is Creativity The New STEM?

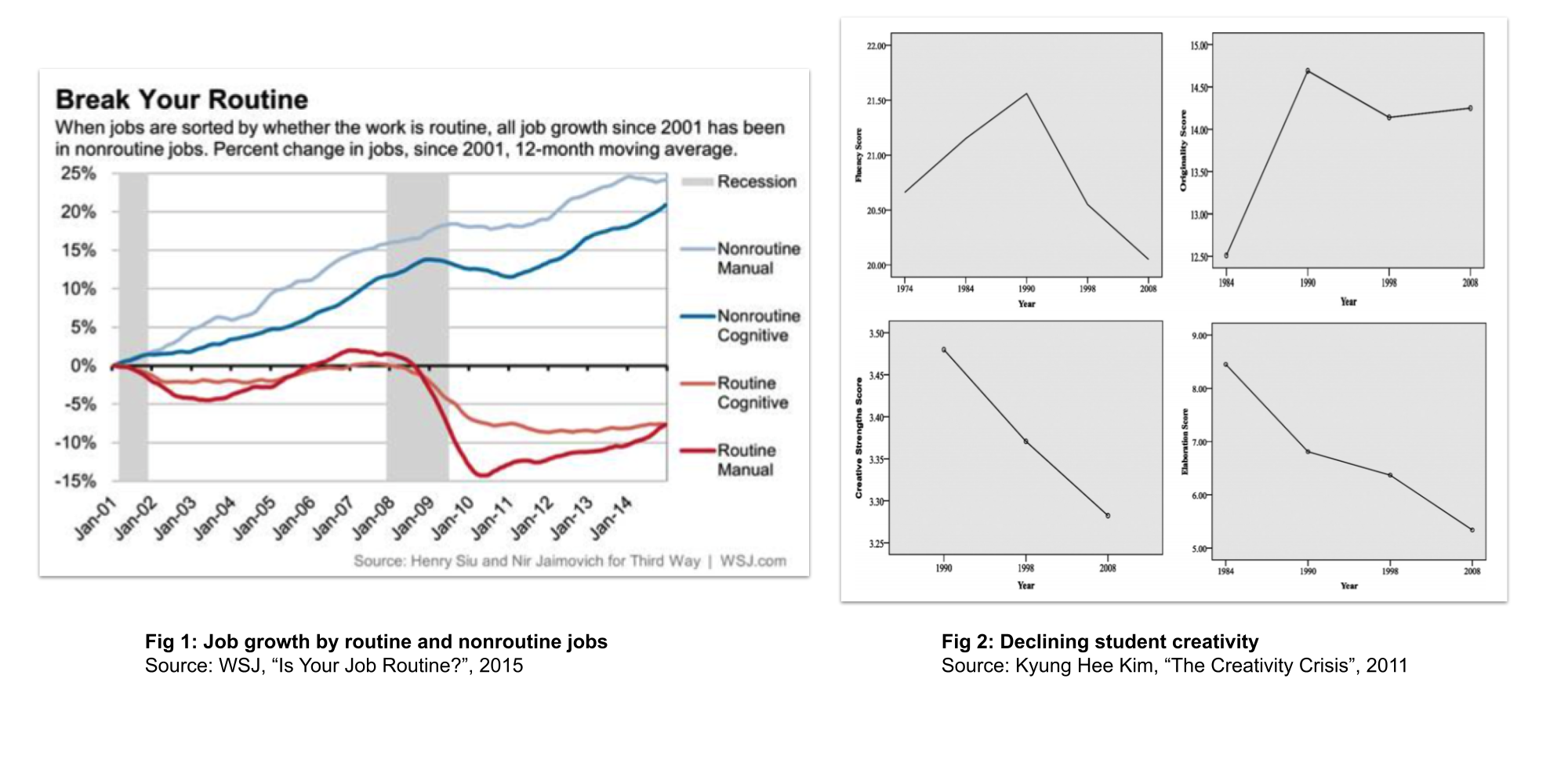

The impact machine learning is having on human livelihood brings us to the first graph (Fig. 1).

Research by economists Henry Siu and Nir Jaimovich shows that economic growth over the last two decades has come entirely from non-routine, or creative jobs. Routine work – both manual and cognitive – has been steadily declining due to automation. Machines learning is getting better at increasingly complex tasks, performing them with fewer errors compared to humans.

We are teaching machines to be more like humans, and we are doing that quite well.

As a side note, the graph also shows that every recession accelerates the decline in routine work, and in a few years we will learn the full impact of covid on long-term job trends.

The current situation is reminiscent of the early 2000s when various reports (e.g. Rising Above the Gathering Storm) raised concerns about the quality of math and science education, and the shortage in the STEM workforce to meet the growing demand.

In response to that Obama, who had earlier called STEM education our “Sputnik” moment, announced incentives for schools that create STEM programs for their students in his 2013 State of the Union address. That triggered an intense focus on STEM education from many players including schools, nonprofits and the technology industry. These efforts have paid off to an extent. Access to coding and other STEM programs is much more easily available to students of all age groups and backgrounds now. There are indications that although we have a scarcity of STEM graduates in certain geographical areas and domains, we also have a surplus in others.

We are yet again at a junction where economic forecasts are pointing to the need for a skill that isn’t being adequately addressed. It’s likely that Creativity is the STEM of this decade.

The Decline of Student Creativity

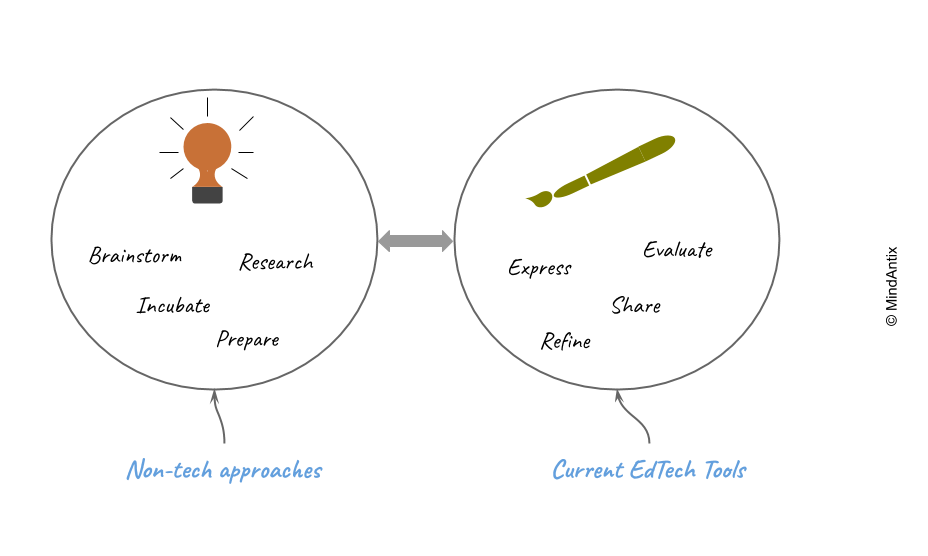

How well students are doing in their creative thinking abilities brings us to the sobering reality of our second graph (Fig. 2).

Professor Kyung Hee Kim first discovered that student creativity as measured by the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT) has been declining since the 1990s and her analysis led to the highly popular Newsweek article, The Creativity Crisis. She found that measures like originality (thinking of novel ideas) and fluency (thinking of several ideas) – the hallmark of creativity – have shown a significant decline over the years.

Part of the reason for this decline, according to Prof. Kim, has been the heavy and narrow focus on standardized testing which doesn’t leave room for building higher order thinking skills. Learning in school heavily prioritizes “one right answer”, which machines are good at, as opposed to multiple possible solutions, which give students the opportunity to exercise their creative muscle. Or as Sir Ken Robinson expressed, “we are educating people out of their creative capacities.”

Current EdTech tools used in schools aren’t helping either – they primarily help students express their creativity instead of building it.

In other words, we are teaching humans to be more like machines, and unfortunately, we are doing that quite well too.

Navigating the Skill Gap

Educators have long recognized the importance of fostering creativity as part of student learning but the current economic environment is making this an urgent need.

The good news is that creativity is a cognitive skill that can be developed with practice, and cognitive creativity programs have shown promising results.

The not-so-good news is that most focus on divergent thinking which is disconnected from academic content students are learning. As one study pointed out, “It is hard to see how listing 100 interesting and unusual ways to use egg cartons will help Johnny improve his scores on state-mandated achievement tests.”

One approach taken at MindAntix is to identify thought patterns, like associative or reverse thinking, that aid in creative thinking and actively incorporate them into school curriculum. Other educational approaches, some of them domain specific, have also been effective in improving creativity which offers room for some optimism.

If we start teaching humans to be better at what makes us uniquely human – our ability to think creatively – we stand a much better chance at improving educational and career outcomes for our students.

This article first appeared on edCircuit.