With the rapidly evolving business landscape in the age of AI, the ability to innovate and adapt is paramount. For CEOs and business leaders, cultivating an entrepreneurial mindset within their organizations is more than a strategy—it’s a necessity. This mindset, characterized by agility, creativity, and resilience, can be the difference between thriving and merely surviving. Drawing on the examples of visionary leaders like Yvon Chouinard, Tony Hsieh, and Satya Nadella, we can see how adopting an entrepreneurial mindset can drive success.

What Is An Entrepreneurial Mindset?

Most people have an intuitive understanding of entrepreneurial mindset. A more formal definition, following an exhaustive review of published work, defines entrepreneurial mindset as “a cognitive perspective that enables an individual to create value by recognizing and acting on opportunities, making decisions with limited information, and remaining adaptable and resilient in conditions that are often uncertain and complex.”

In hypercompetitive markets, becoming more entrepreneurial is crucial for adapting to emerging threats and staying ahead of competitors. Such strategic entrepreneurship requires a special kind of leadership—entrepreneurial leadership.

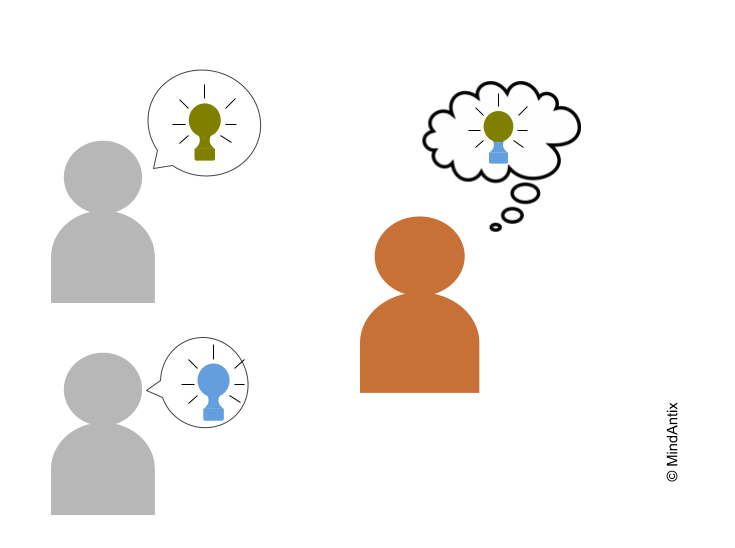

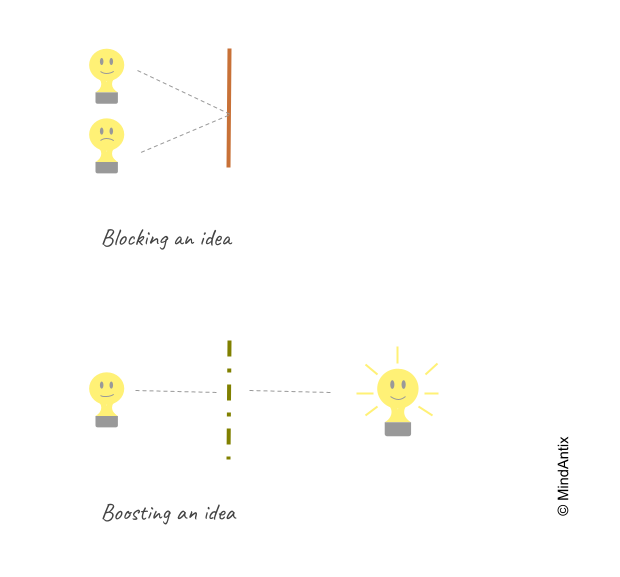

Individuals exhibiting such leadership behaviors are pivotal in steering their organizations towards innovation as a company’s culture and leader’s entrepreneurial mindset are interconnected. This relationship between culture and mindset is recursive, and modeled as an entrepreneurial spiral. The bottom-up process of the spiral represents the influence that a company’s entrepreneurial culture has on the leader’s mindset. Simultaneously, the leader’s entrepreneurial mindset can have a top-down effect on the culture, fostering an environment that is more entrepreneurial. Both the top-down and bottom-up processes can result in a positive feedback loop that grows a company into a more innovative state.

Key Traits Of Entrepreneurial Leaders

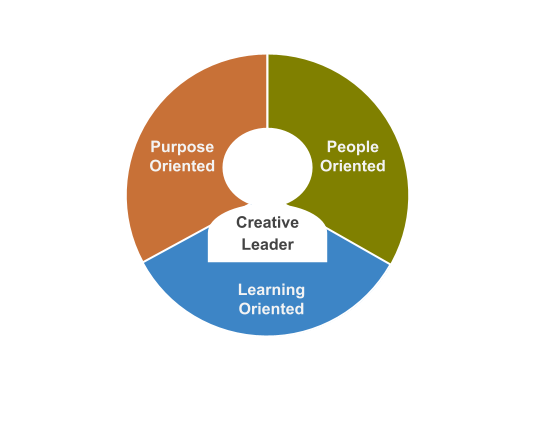

The essence of an entrepreneurial leader can be distilled into three core entrepreneurial mindsets: people-oriented, purpose-oriented, and learning-oriented. Visionary leaders such as Yvon Chouinard of Patagonia, Tony Hsieh of Zappos, and Satya Nadella of Microsoft exemplify these traits, having guided their companies to remarkable achievements.

People-Oriented Mindset: Tony Hsieh

A people-oriented mindset has two factors: staying inclusive and open; and being positive and appreciative of employees. This mindset fosters a positive and supportive work environment, where employees feel valued and empowered. Leaders with a people-oriented mindset are more likely to win the support and trust of their employees and team members.

Tony Hsieh, the late CEO of Zappos, was an example of a leader with a people-oriented mindset. He made employee happiness a cornerstone of Zappos’s culture. Hsieh implemented a flat organizational structure at Zappos, which minimized hierarchy and encouraged autonomy among employees. This empowerment allowed team members to make decisions that they felt were in the best interest of customers, fostering a sense of ownership and responsibility. Hsieh’s emphasis on employee satisfaction also led to the implementation of groundbreaking policies at Zappos, such as offering new hires a “quitting bonus” if they didn’t feel aligned with the company’s culture. This bold move ensured that the team remained highly motivated and committed, fostering an environment where innovation and exceptional customer service could flourish.

Purpose-Oriented Mindset: Yvon Chouinard

A purpose-oriented mindset has two main aspects: keeping the end goal in mind and having the endurance to see it through. Leaders with this mindset have a unique ability to balance their focus on the objective with the patience necessary to achieve it. This equilibrium is rooted in their deep commitment to their purpose.

Patagonia’s founder, Yvon Chouinard, is an excellent example of a purpose-driven leader. He has instilled in his company a strong dedication to environmental preservation. Patagonia’s initiatives, which range from using recycled materials in their products to supporting environmental causes, reflect Chouinard’s unwavering belief in sustainability. Under his leadership, Patagonia has not only talked the talk but also walked the walk, setting an example for the industry and consumers alike. Patagonia’s efforts, such as the “1% for the Planet” pledge, which commits the company to donating 1% of its sales to environmental groups, have inspired other businesses to follow suit. Patagonia’s dedication to environmental and social issues has also resonated with consumers, resulting in a loyal customer base that has contributed to the company’s financial success.

Learning-Oriented Mindset: Satya Nadella

A learning-oriented mindset is characterized by two key attributes: an ability to pick signals from all around and an inclination to take risks. A learning-oriented mindset allows leaders to seize opportunities. Moreover, the calculated risks taken by these leaders inspire their employees to follow suit.

Satya Nadella’s success at Microsoft is a testament to the power of a learning-oriented mindset. He was quick to recognize the potential of cloud computing, and steered Microsoft’s efforts in that direction making Azure a major competitor to Amazon Web Services. More recently, Microsoft’s partnership with OpenAI, and his push to integrate advanced AI technologies into its various offerings, demonstrated Nadella’s ability to act decisively on emerging technological trends. This strategic move positioned Microsoft at the forefront of AI development. Nadella’s initiative to foster a growth mindset at Microsoft, encouraging employees to embrace a “learn-it-all” as opposed to a “know-it-all” approach, highlights his commitment to creating a culture of continuous learning, experimentation, and adaptation. By fostering an environment that values learning and growth, Nadella has revitalized Microsoft’s innovation engine.

Blueprint For Creating Innovative Companies

The journey to fostering an entrepreneurial mindset within an organization is multifaceted. It requires leaders to be purpose-driven, people-oriented, and committed to continuous learning. Leaders who embrace these principles can transform their organizations, creating a culture that not only survives but thrives in the face of change. To cultivate an entrepreneurial mindset, leaders should focus on embedding these traits within their organizational culture. Here are three ways leaders can adopt to build a more entrepreneurial culture.

- Embrace a clear and compelling purpose. Leaders should articulate a clear and compelling purpose for their organization that employees can rally behind. This purpose should be something that employees are passionate about and believe in, and it should provide a sense of direction and purpose for their work. An inspiring purpose goes beyond profits or mission statements and addresses the “why” of a company’s existence. For Patagonia, environmental sustainability is a purpose that goes beyond individual or company interests which makes it inspiring for employees to adopt.

- Encourage open communication and collaboration. Leaders should encourage open communication and collaboration within their organizations. This open communication needs to be bidirectional allowing employees to also express their concerns, challenge assumptions and share their own ideas. The bottom-up part of communication helps leaders get better signals about new technologies and use cases that eventually aid their strategic thinking. In contrast to Nadella, Steve Ballmer mocked the iPhone when it first came out, and completely underestimated its market success. Allowing open collaboration to test out experimental ideas helps identify new areas of innovation — signals that leaders can use in strategic planning.

- Create a positive and supportive work environment. Leaders should create a positive and supportive work environment where employees feel valued and respected. What made Zappos a great place to work was the autonomy that Hsieh provided to all employees, empowering them to go beyond scripted responses and make on-the-spot decisions that were in the best interests of the customer. As a result, employee turnover at Zappos was significantly lower compared to industry average.

By following these strategies, business leaders can create a high-performing and innovative workplace.