Every disruptive tool in the history of technology has reshaped not just what we work on, but how we work. The advent of cloud computing didn’t just speed up software delivery—it transformed the entire product mindset. Companies moved from slow, waterfall models to agile, continuous delivery of services. Speed, iteration, and customer responsiveness became the new north stars.

Today, generative AI is prompting a similar reckoning. Its ability to produce code, content, and prototypes at lightning speed forces us to ask: What does meaningful work look like in an era where execution is cheap and near-instant? How do we organize for innovation when the tools themselves are evolving daily?

To answer these questions, we need to rethink how teams are built, how cultures are shaped, and how success is measured. The future of work is more about reconfiguring human work for a landscape where ideation, experimentation, and adaptability are the new competitive advantages, than simply automating tasks.

To navigate this next frontier, we need to understand the major trends reshaping the future of work in technology.

Trends

The Cost of Execution is Plummeting

Just a few years ago, building a minimum viable product (MVP) required a team of developers, designers, and weeks (if not months) of effort. Today, a capable generalist with access to tools like GitHub Copilot can spin up a working prototype in hours.

This shift is quantifiable. GitHub’s 2024 productivity report showed developers using AI coding tools completed tasks 55% faster, with higher focus and reduced mental fatigue. MIT and Microsoft researchers found similar results: a 56% speed increase when software engineers used AI as a pair programmer.

But as execution becomes commoditized, it ceases to be a differentiator. What matters now is what you build, why it matters, and how quickly you can learn from real users. Competitive advantage is shifting from efficiency to experimentation and product-market fit.

In short: in a world where everyone can build fast, those who explore better will win.

We’re Still in Exploration Mode

Despite the excitement, generative AI is still far from plug-and-play. Integrating these tools into real-world business workflows is messy, expensive, and often unreliable. And while AI is great at generating content or code, it’s still brittle when it comes to reasoning, context, or strategy.

The so-called “killer apps” of generative AI—the ones that will reshape entire industries—haven’t yet arrived. According to McKinsey’s 2024 report on GenAI, only about 10% of organizations report significant value from GenAI, and many pilots are failing to scale due to unclear ROI and integration challenges.

This places us squarely in the exploration phase of innovation. It’s tempting to force AI into existing processes, expecting predictable outputs. But the real opportunity lies in experimenting, probing new use cases, and embracing ambiguity.

Exploration is no longer “a nice to have”. It’s become essential. And organizations must build the capacity to explore without immediate payoff if they want to discover the next big thing.

Pressure to Innovate is Rising

All of this is happening against a backdrop of increased volatility: shifting customer expectations, economic uncertainty, and rapid technology cycles. Leaders are feeling the squeeze—needing to innovate faster while also managing risk.

But here’s the paradox: too much pressure can kill innovation. Research from Teresa Amabile has shown that high-pressure environments oriented around extrinsic rewards tend to suppress creativity. People become more risk-averse, less exploratory, and more focused on pleasing stakeholders than experimenting with new ideas.

To survive and thrive, tech companies must shift their mindset from optimization to experimentation, from managing work to designing conditions for innovation.

This leads us to the second core pillar of the future of work: how we organize and empower people in order to harness collaborative Intelligence.

Building Blocks of Collaborative Intelligence

The old myth of the lone genius persists in tech but it’s increasingly out of step with today’s reality. Today’s problems like ethical AI, climate tech, platform trust are inherently complex. Solving them requires multiple perspectives, disciplines, and heuristics. No single individual, no matter how brilliant, can fully grasp the nuance alone.

Scott Page’s research on cognitive diversity shows that heterogeneous teams consistently outperform homogeneous ones when tackling non-routine, complex tasks. Diverse thinkers bring different models, biases, and blind spots which, when managed well, leads to better problem-solving.

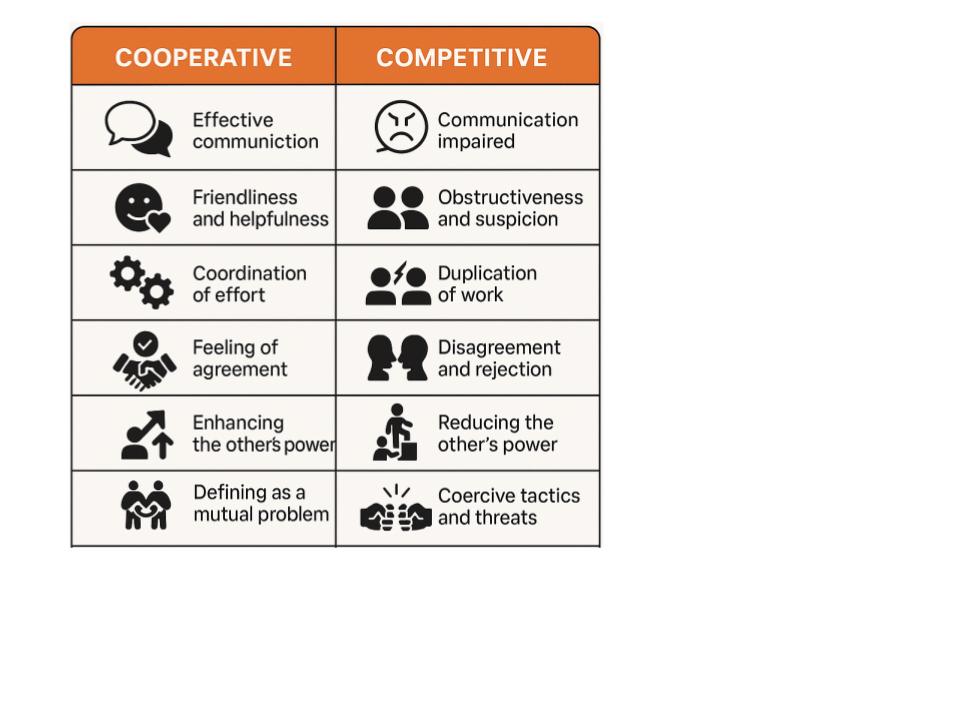

But this collaborative intelligence doesn’t happen by accident. It requires the right mix of people, culture, and incentives. Let’s break that down.

People

In this new world, depth of expertise isn’t enough. What’s needed are T-shaped individuals—people who possess deep expertise in a specific area (the vertical bar of the “T”), but also broad skills and curiosity that allow them to collaborate across domains (the horizontal bar).

These individuals are connectors, translators, and creative synthesizers. They’re engineers who understand user research, product managers who code, designers who analyze data. They can shift gears from deep work to cross-functional problem-solving with ease.

IDEO, which helped popularize the concept, found T-shaped people to be central to high-performing innovation teams. And organizational research confirms this: T-shaped professionals are more adaptable, more comfortable with ambiguity, and better at generating creative solutions in multidisciplinary settings.

Hiring for T-shaped talent builds not just execution capacity, but also resilience and adaptability.

Culture

Culture is the invisible force that either enables or crushes innovation. Yet many companies cling to outdated models of top-down hierarchies, rigid approval systems, and fear-based management.

To foster exploration, cultures must be reengineered around the principles of Self-Determination Theory (SDT), developed by psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan. According to SDT, people are most intrinsically motivated, and therefore most engaged and creative, when three core psychological needs are met:

- Autonomy: The feeling that one can direct their own work and make meaningful choices.

- Competence: The sense of being capable and growing in one’s abilities.

- Relatedness: Feeling connected to others and contributing to something larger..

A culture rooted in SDT doesn’t just produce happier employees. It produces better ideas.

Incentives

Traditional incentive structures—performance bonuses, individual KPIs, stack rankings—are optimized for predictability and efficiency. They reward execution, not experimentation.

But as research from both Deci & Ryan and Amabile shows, extrinsic rewards often undermine intrinsic motivation, particularly for creative work. When people work only for outcomes, they become risk-averse. They choose the safe path, not the inventive one.

To build a future-ready organization, leaders must rethink what they reward:

- Celebrate collaboration, not just individual brilliance.

- Reward learning, even when projects fail.

- Make space for intrinsic goals, like mastery, curiosity, and purpose.

Shifting incentives in this way doesn’t mean abandoning accountability—it means realigning it with innovation.

Final Thoughts

AI is shifting our focus from how we execute to how we explore, learn, and adapt. In this new landscape, competitive advantage will belong, not to those who can scale fastest, but to those who can reimagine the way teams think, build, and evolve together.

This requires more than new tech—it requires reconfiguring the foundations of work.

In the next part of this blog, we’ll explore how to redesign teams for this future. The future of work is not a question of whether we change, but how intentionally we do so.