How do you think Charles Darwin, George Bernard Shaw and Isaac Newton, would have fared as students in today’s world? From what we know about their lives, they all got less than stellar grades in school and would likely not have qualified for any school district’s gifted program. Despite that, they all made lasting and valuable contributions in their fields. These examples, among others, have been a subject of many debates about what intelligence is and what the role of education should be. If IQ, which correlates well with grades, is not enough for great accomplishments, then what is?

Psychologist, Joseph Renzulli, has spent decades on understanding “giftedness”. He identified two forms of giftedness, which are both important and usually interact with each other. The first, schoolhouse giftedness, is the kind that is measured with IQ tests (cognitive ability) and correlates well with school grades. The other, creative-productive giftedness, is the kind where the creative ideas and work have an impact on others and cause change. Or, in other words, the domain-transforming, culture-changing kind of giftedness that results in an Einstein or a Mozart. Interestingly, it turns out that you do not need to have an off-the-charts IQ to be a creative genius of that caliber.

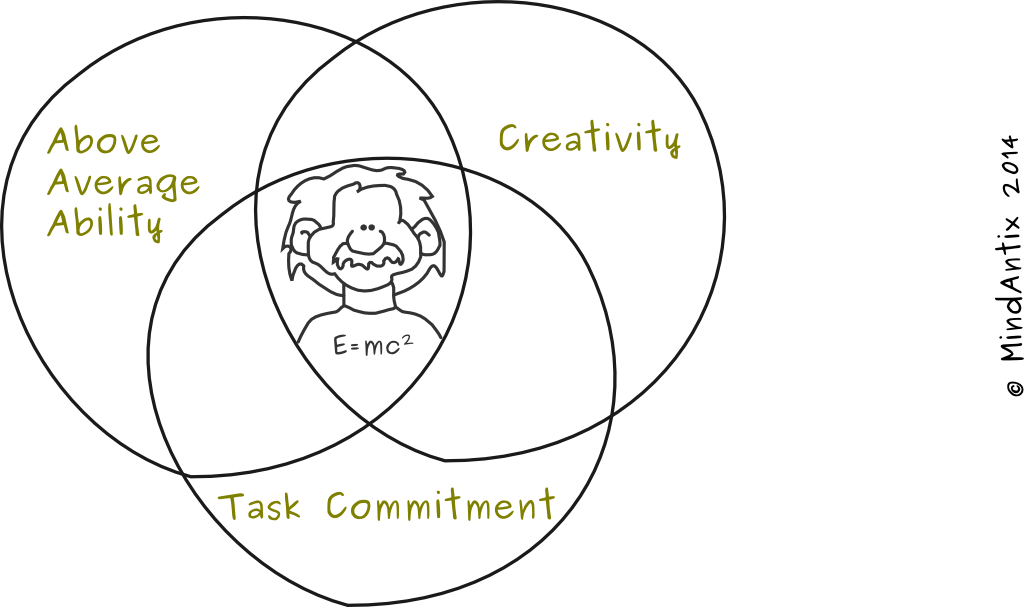

Renzulli identified three clusters of traits, summed up in his Three-Ring Conception of Giftedness, that are required to be creative-productive. It is the interaction between the three clusters that creates creative-productive accomplishment. Teresa Amabile, a professor at Harvard, also arrived at a similar set of components in her Componential Theory of Creativity.

-

Above-Average Ability: Creative geniuses have above average ability in both general abilities (like general intelligence) and specific abilities (like in specific areas like mathematics and ballet). However, above average ability doesn’t imply superior ability. In fact, Renzulli believes that performance in the top 15-20% is usually sufficient for high accomplishments.

-

Task Commitment: Creative geniuses have a focused form of motivation that Renzulli and Amabile call task commitment. This includes factors like grit, intrinsic motivation, perseverance, hard-work that help the creative genius stick with the task long enough to overcome challenges and achieve success.

-

Creativity: Creative geniuses also possess the ability to envision original and fresh approaches to problems, the ability to set aside established conventions. Amabile highlights some cognitive styles and heuristics – like suspending judgment, trying something counter-intuitive or choosing wide categories – that can help build creativity and generate novel ideas. The challenges we design at MindAntix are built around these (and more) heuristics to help people learn to think in more diverse ways.

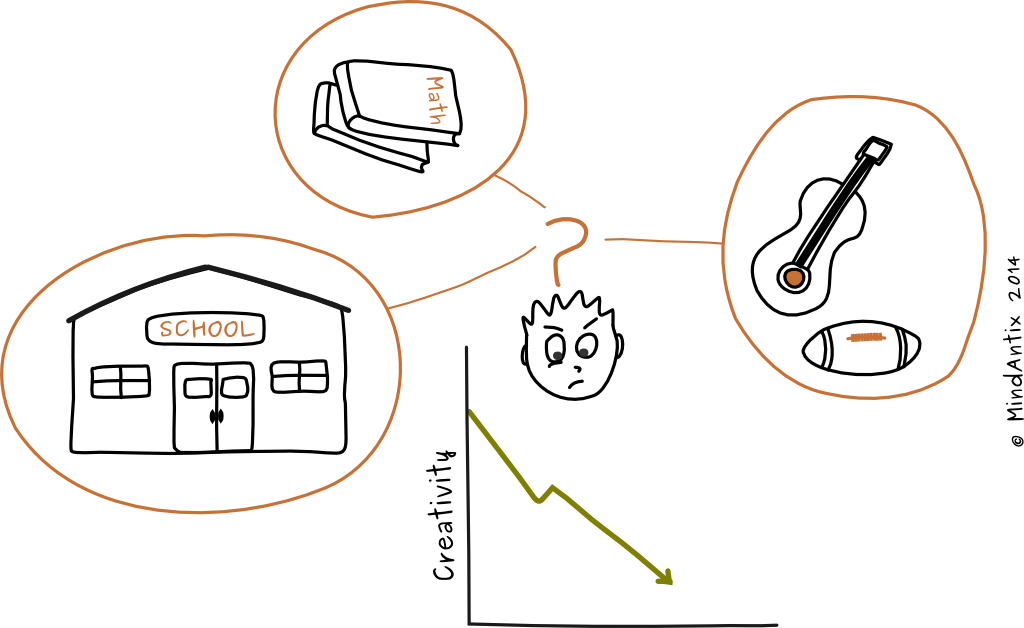

Our culture emphasizes schoolhouse giftedness – leaning too heavily on building analytical skills – sometimes at the expense of building other traits. However, as Renzulli discovered, creative geniuses are well-rounded – they have high levels of creativity and perseverance that help them achieve bigger goals. Nurturing creativity and building grit can have a bigger impact on building geniuses than focusing entirely on academic skills. Recent studies point to some clues on building grit – pursuit of engagement and meaning, as opposed to pleasure, help build the right kind of motivation that enables grit. Creative thinking skills can be developed by practice – the SCAMPER technique is a useful brainstorming tool to use with your child in solving open-ended challenges. But more importantly, the next time your child spends hours absorbed in a task or uses a little creativity in solving her problem, take comfort in the fact that she is building crucial skills for success.