During a period of six months in 1821, Michael Faraday conducted a series of well-thought out experiments that broke some of the earlier theories about electricity and resulted in the first electrical motor. A few months before that, Oersted had discovered that electrical current flowing through a wire, could affect the orientation of a magnetic compass nearby. Over several experiments, Faraday showed that the magnetic field produced by the electrical current was circular in nature, and that electricity and magnetism could be used to produce motion.

But equally important is the experiments he chose not to do. For instance, he didn’t run an experiment to see the effect of electricity on the magnet under different light conditions. Why? Because it would not make sense to do so given what scientists knew about the nature of electricity.

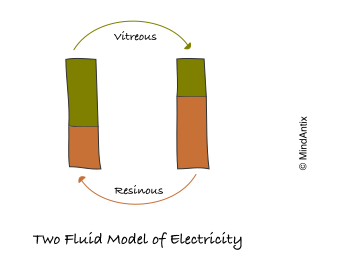

The existing models that scientists had about electrical current had nothing to do with light. The prevailing notion of electricity at that time was that it was a material fluid as opposed to an energetic condition and completely independent from magnetism. So the experiments that Faraday designed were carefully constructed to either confirm or refute existing models of electricity and magnetism. And that’s what led him to advance the field of electromagnetism.

Unfortunately, the Scientific Method (TSM) as taught in schools today often misses this finer point.

To do a science fair project students often pick a question from a pre-existing list or construct one hastily with no real rationale based on their understanding of how the system or phenomenon works. The emphasis is on following the steps in the scientific process which effectively makes the whole exercise a guessing game with no deeper learning attached to it.

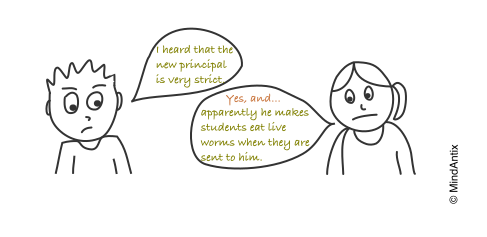

In a study of science education in schools, researchers looked at how middle school students in a classroom were approaching inquiry experiments on plants. Students came up with several ideas like feeding the plant coke, using various kinds of dyes or different types of soil. However, the teacher never asked why any of those questions make sense. As the authors explain, “Do these students have any reason to believe (or hypothesize) that the physiology of a plant will respond in particular ways to these features in their environment? Because such questions are arbitrary—i.e., make no sense without the context of at least a beginning model for understanding the phenomenon—then any hypotheses emerging from these questions are likely to be little more than poorly informed guesses.”

In fact the most creative parts of science – generating hypotheses, theorizing from observations and designing experiments – get lost in the traditional approach of strictly following the scientific method.

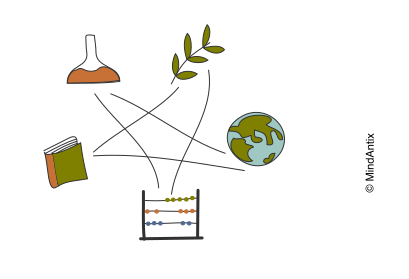

So what exactly is Model Based Inquiry (MBI)? Using MBI allows students to develop “defensible explanations of the way the natural world works”, and it uses four kinds of conversations (often in an iterative fashion):

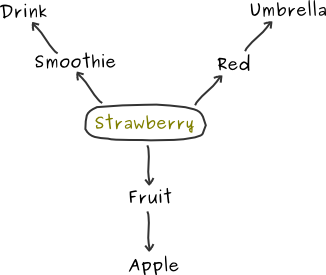

- Organizing Prior Information: Without knowing something about a subject, or in other words without a starting model, constructing any hypothesis is like a shot in the dark. So the first step is to list out any information you already have – what the different components and elements are and how they related to each other.

- Generating a Testable Hypothesis: Once students have an initial model, the next step is to generate hypotheses that are grounded in the model. The idea is to generate competing hypotheses to test specific aspects of the model, that can help deepen understanding of the underlying concept.

- Seeking Evidence: This part of the conversation is around figuring out what kinds of data to collect to test the model, which can then be used to support an argument.

- Constructing a Scientific Argument: The final conversation which is often missing in practice, is to tie it back to the model to support or refute specific claims about the model.

While at a high level this may look similar to the scientific method, the focus on the model during the process makes a big difference.

The scientific method, while being a very useful tool for structured thinking, has the side effect of oversimplifying science in education and going further away from how real scientists actually reason and think in science. Incorporating MBI has the potential to change how students relate to science and engage them at a deeper level.