When patrons were seated at El Bulli, during its prime, the first thing they would get was an olive.

Or, at least, what looked like one. They would pick up the “olive” resting in a spoon and bite gently, only for it to collapse into a warm, intensely flavored liquid that instantly flooded the palate and then disappeared.

That small bite of the now legendary spherical olive was much more than a novelty. It was the successful outcome of countless experiments using a technique called spherification, which turns olive juice into delicate spheres using alginate and calcium salts. The El Bulli team had to tackle real-world challenges to create it: How do you make a membrane thin enough to melt in your mouth, but strong enough to survive being plated? How do you make the process reliable so you can repeat it hundreds of times a night? And how do you make sure every guest has the exact same moment of surprise with that very first bite?

It is a case study in radical innovation.

Everything the tech world struggles with—finding the sweet spot between creativity and discipline, quickly moving from idea to experiment, collaborating across different fields, and building teams focused on growth rather than just resumes—was being figured out in this remote kitchen on Spain’s Costa Brava.

So, here are four key lessons from El Bulli’s kitchen that translate well to today’s product and innovation teams.

1. Creativity is the core system, not a side project

El Bulli did something revolutionary: it closed for half the year, from roughly October to March. This allowed Ferran and Albert Adrià and their core team to focus entirely on creativity. They spent those months inventing new techniques, testing fresh ideas, and developing the next season’s tasting menu, which often featured 30 or more incredible courses.

By the time the restaurant closed its doors for good in 2011, the team had created about 1,800 dishes and pioneered game-changing techniques like spherification, foams, and warm gels that reshaped high-end cooking worldwide.

A few things stand out:

- Dedicated time: Creativity wasn’t an afterthought, squeezed into weekends or the “10% time” left after service. Half the year was deliberately reserved for exploration.

- Permission to break rules: Inside that creative window, the brief was to question everything. Dishes could be deconstructed, recomposed, or turned inside out. Tradition was a reference point, not a constraint.

- Discipline in service of magic: For all the experimentation, the final measure of success was simple: did it create a magical experience for the guest? El Bulli eliminated the à la carte menu so that every guest received a carefully choreographed tasting sequence, built from scratch each season around these new creations.

This raises some important questions for tech companies: Is creativity truly built into your structure, or is it just something people are expected to do after the “real work” is done? How do you maintain a high standard that encourages teams to experiment but still ensures a compelling user experience at the end of the day?

2. Start from first principles: “What is a tomato?”

Ferran Adrià is famous not only for his bold dishes, but for the questions behind them. Again and again, he and his team would come back to deceptively simple prompts: What is a tomato? What is soup? What is a salad?

In interviews about his work, Adrià often challenges common assumptions. For example, he points out that the original “natural tomato” in the Andes was actually inedible. What we enjoy as a tomato today is the result of human intervention through breeding, selection, cultivation. In other words, even the most ordinary ingredient is already a designed product.

This is what first-principles thinking looks like in action. Instead of just the category of “tomato” as fixed, he breaks it down:

- Where does it come from?

- What is its essence—its acidity, sweetness, aroma, and texture?

- What aspects should stay unchanged, and which parts are negotiable?

This intellectual groundwork is what powered the deconstructionist cuisine that made El Bulli famous: taking a familiar dish, radically changing its form, texture, or temperature, but making sure its underlying essence remains intact.

In the tech world, we often talk about first principles, but in practice we work from mental templates: “It’s a CRM, so it needs to look like a sales funnel; it’s a learning platform, so it has to have modules and quizzes.”

The El Bulli approach would sound more like this for a product team:

- What is a meeting? Is it really just a slot on a calendar, or is it a ritual for making decisions that could take on a completely different shape?

- What is a classroom? Is it defined by a physical room and a timetable, or is it actually about a set of relationships and feedback loops that could be designed differently?

For Adrià’s team, these questions weren’t theoretical. They were directly linked to real kitchen experiments. When they clarified the true essence of a dish, it gave them permission to change everything else about it.

Product teams can adopt this powerful discipline, too: clearly define the non-negotiable essence of the user problem or the desired outcome. Once you have that clarity, you’re free to completely rethink the structure, the interface, or even the business model.

3. Keep the idea-to-experiment loop radically short

One of the most revealing aspects of El Bulli’s creative culture is not on the plate, but on paper.

Museums such as The Drawing Center in New York have mounted exhibitions called Ferran Adrià: Notes on Creativity, displaying his sketches, diagrams and visual maps. These sketches offer a glimpse of how he thought and emphasize drawing as a tool for thinking. It helped externalise ideas quickly, organise knowledge, and communicate concepts to the team.

The creative process started with a rough sketch that captured the initial thought. That sketch immediately leads to a simple kitchen prototype which the team evaluates and iterates till the idea is perfected.

What you do not see are lengthy slide decks, layers of approval, or months spent debating concepts before anyone picks up a pan. Instead, the kitchen becomes the thinking environment. The sketches move an idea from an internal hunch to a shared experiment quickly, not to impress anyone in a meeting.

When we’re building products, we often do things backward. We spend weeks making perfect presentations about an idea before a single user ever sees it. As a result, we invest a lot of time justifying something that hasn’t been tested in the real world.

What if we took inspiration from the El Bulli approach to ask:

- Could you sketch out a major idea in less than five minutes?

- Could you build the very first version of a new concept in a day and get it in front of a real user within a week?

- Could we simplify the number of sign-offs needed to run a small experiment?

This isn’t about being reckless. At El Bulli, the final menu was obsessively refined. But the path from idea to first test was deliberately short. And autonomy was real: talented people were trusted to try things without seeking permission for every iteration.

When teams make the idea → experiment → learning loop shorter, they tap into creative energy that can turn a crazy idea about a “spherical olive” into a world-famous dish.

4. Treat innovation as a team sport across disciplines

El Bulli’s breakthroughs were not only the work of a couple of geniuses. Every dish came to life thanks to a whole team of experts: chefs, pastry specialists, food scientists, industrial designers, and even the folks running the front of the house.

Albert Adrià’s own journey illustrates this. He joined El Bulli as a teenager in 1985, spending his first two years rotating through all the stations in the kitchen before focusing on pastry. Over time he became head pastry chef and then director of elBullitaller, the Barcelona-based creative workshop that served as the restaurant’s R&D lab during the closed season.

In interviews and profiles, he always emphasised that it was the team, not individual brilliance, that made El Bulli exceptional. The creative work depended on people who were:

- Deeply curious and willing to learn fast.

- Comfortable collaborating across roles rather than jealously guarding territory.

- Motivated by the shared goal of creating something extraordinary for the guest, rather than building personal fame.

The spherical olive itself was a multidisciplinary artefact. It required understanding the chemistry of alginate and calcium, mastery of textures and temperatures, and careful design of the serving ritual so that each guest ate it in a single bite at the right moment.

For business leaders, there are two intertwined lessons here.

Multidisciplinary structures

Radical ideas often sit at the intersection of fields yet many organisations still arrange teams in narrow silos.

El Bulli suggests a different model for breakthrough ideas: Instead of keeping teams separated in silos, bring diverse perspectives together. In practice it would mean getting designers, engineers, data analysts, and subject-matter experts collaborating side-by-side in small, cross-functional “innovation pods.” This way, everyone can see and shape the idea from the very start, using shared visual tools like maps and sketches. It’s about co-creating, not just passing a task down a line.

Hiring for growth mindset, not just pedigree

Albert did not arrive at El Bulli with great credentials. He came as a 16-year-old apprentice and grew into one of the most influential creative forces in modern pastry, precisely because he was willing to experiment relentlessly and learn from others.

Translating that mindset into hiring means asking:

- Does this person show evidence of rapid learning across domains, or only depth in one?

- Do they light up when they talk about collaboration, or only when they describe solo achievements?

- Are they comfortable with ambiguity and experimentation, or do they need everything defined upfront?

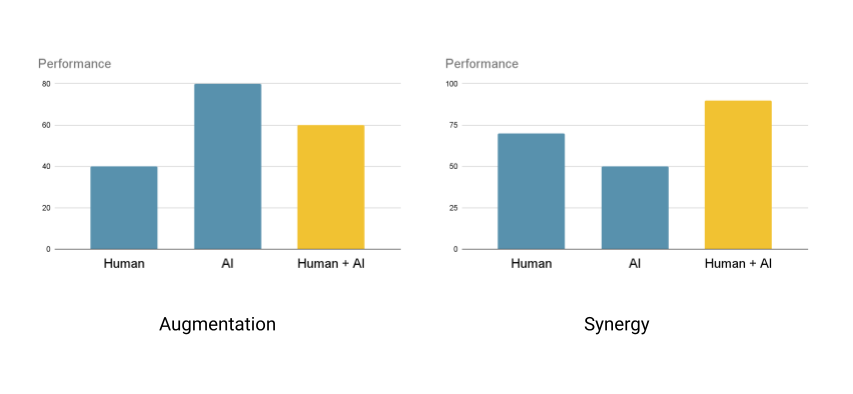

In a world where the most interesting problems are inherently multidisciplinary like climate tech, future of learning, human–AI collaboration, it is often more valuable to hire people who can grow into the unknown than those who perfectly match yesterday’s job description.

Bringing El Bulli’s lessons into your organisation

For all its mystique, El Bulli was, at heart, a working laboratory. It dealt with constraints familiar to any leader: limited time, finite resources, high expectations, and the pressure to keep surprising a demanding audience.

Its response was not to work harder in the same way, but to redesign the system around creativity:

- Carve out time for exploration.

- Ask first-principles questions again and again.

- Move ideas quickly from conception to experiment.

- Allow multi-disciplinary teams to work closely.

- Hire people for their capacity to learn and collaborate.

These principles apply just as well to innovative companies. When you do so, you begin to treat creativity not as a garnish, but as the main ingredient—tempered by discipline, grounded in first principles, and always aimed at giving the people you serve a truly memorable experience.

Image credit: The Drawing Center