One of the earliest technologies that gained wide user adoption was the calculator. Pocket size versions of the calculator became available in the 1970s and it didn’t take long before people started wondering whether children should just learn to use the calculator instead of learning mental mathematics.

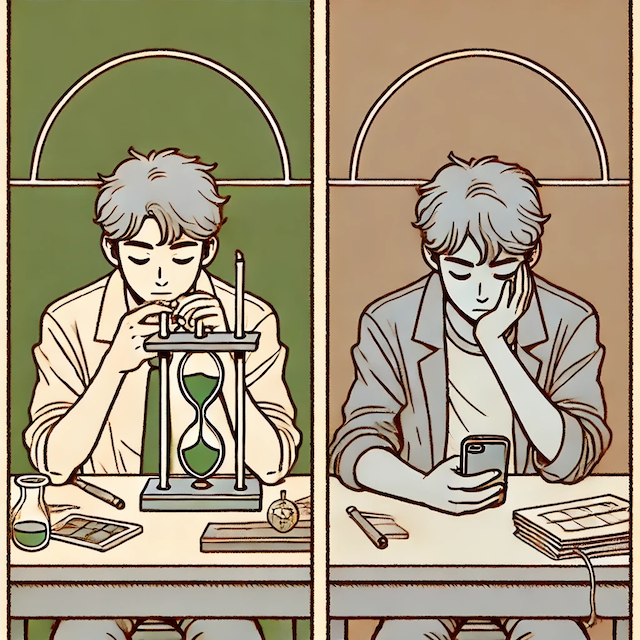

Thankfully, the educational system continued to teach basic arithmetic to young students for a very good reason. Students don’t just need to understand the concept of addition or multiplication. They need to practice arithmetic over and over again in order to build and strengthen the right neuronal connections for computational fluency. High computational fluency is correlated with better performance in more advanced math, so doing there drills in early years sets the foundation over which more complex mathematical thinking can be built.

With the coming of AI, especially Large Language Models (LLMs), we are seeing a similar debate take place. The popular line of reasoning — AI is undoubtedly going to be a big part of our lives going forward and students need to learn how to use it — makes logical sense.

But perhaps that’s precisely the reason why we shouldn’t teach students to use AI.

What Is The Goal Of Education?

There are different philosophical views about the goal of education, but most people would agree that education is about building the right skills so students can thrive in the real world. The point is never to teach students about all possible tasks that they might have to do, but to build enough of the right foundational skills that will allow them to adapt, learn new things and make meaningful contributions. This is why higher order skills, like creative and critical thinking, feature on the top rungs of Bloom’s taxonomy, a hierarchical model of learning goals that guides our educational philosophy. This makes sense because it is nearly impossible to predict the kinds of jobs that will exist a decade or two later. So teaching specific domains is less important than building higher order cognitive skills that will allow students to be successful, no matter what tasks they might have to face.

Cognitive Complexity

Consider the two questions below: the first one is taken from College Board’s question for AP World History while the second task asks you to create an AI prompt.

Task 1:

Directions: Question 1 is based on the accompanying documents. The documents have been edited for the purpose of this exercise.

Evaluate the extent to which communist rule transformed Soviet and/or Chinese societies in the period circa 1930–1990.

(See the full question for accompanying documents)

Task 2:

Create a prompt for ChatGPT to help you understand the significance of the American Civil War.

Which of these tasks, in your opinion, is harder?

Most people would agree that the first task is way more complex than the second one.

To complete the first task, students have to quickly read the documents provided, make notes on the historical context, audience, perspective and purpose. As a side note, the documents are varied in nature (e.g. it could be a propaganda poster or a diary entry) and not directly related to the question. Using the provided material as evidence, students have to construct a defensible thesis. They also have to choose an outside piece of evidence that adds an additional dimension, and provide a broader historical context relevant to the prompt. In short, they have to make reasonable inferences from the provided documents and integrate prior knowledge they have about the subject to create a compelling argument. And finally they have to synthesize all of this into a multi-paragraph essay! (Big thanks to my son, who recently took the AP World History test, for helping me understand what goes into answering this type of question).

For the second task, students simply have to ask ChatGPT to explain the significance of the American Civil War! Even if they want to become more sophisticated with their prompting, the strategies (e.g. role-play or providing additional context) are pretty straightforward and easy to learn.

It’s no wonder the AP exam gives students an entire hour to answer the first question, while the second one can be done in just a few minutes.

A more telling sign of the low cognitive complexity of using LLMs, is how quickly people from all ages and walks of life have adopted LLMs to assist them with work tasks. In contrast, not many people have attempted coding, despite the many tools and tutorials that have been available for many years. Teaching STEM skills in schools continues to be a challenge due to the lack of qualified teachers.

Teaching students to tackle complex tasks like the first one has a higher payoff than teaching them simpler tasks. After all, if our education system helps students develop critical thinking skills and the ability to handle tough questions, then easy tasks like the second one will be a breeze for them. Much like the calculator, students don’t need to be taught how to prompt LLMs to get an answer – they need to build skills to answer it themselves.

What Aspects Of AI Should We Teach Students?

It’s clear that teaching students to use LLMs isn’t very useful because we would almost certainly replace a more complex learning goal with a relatively trivial one.

A more worthy goal of teaching AI would be to teach them how AI works so students can build AI models as opposed to simply using them. But this brings us back to square one, because that requires a grounding in programming and computer science fundamentals. So focusing on STEM, coding and computational thinking in the K-12 curriculum is still the right approach to prepare students for careers in technical fields.

Beyond the technical aspects of AI, it’s probably more important for students to understand how to learn better and how AI can impact the learning process. While there are a few scenarios where AI can improve the learning process, there are also learning traps that can harm creative and critical thinking in the long run. Or, they might be better served in building their ethical reasoning skills to tackle the numerous challenges that are bound to arise as AI usage becomes more widespread in society.

All of those would require them to think harder and deeper than simply learning how to use AI.