Bernard Baruch, the American financier and political consultant, once commented that “Millions saw the apple fall, but Newton was the one who asked why.” While it’s hard to imagine that no one else asked why, it is still worth pondering on how Newton managed to solve the puzzle.

Newton did not arrive at the solution in a sudden flash of insight. Instead, the groundwork for reaching his conclusion had been laid over several years before that. Newton had been mulling over what force prevents the moon from shooting off in a straight line at a tangent to its orbit. His breakthrough came when he connected the dots between the force that holds the moon in it’s orbit and the force that causes an apple to fall to the ground. In other words, by using an analogy, Newton was able to create the right hypothesis that eventually led to his theory of universal gravity.

Contrast that kind of thinking with how science fair projects in most schools are approached today. Most teachers (helpfully) give out a list of ideas to base science projects on and the focus is almost entirely on following the scientific process to construct good experiments. However, just like Newton’s discovery, most scientific breakthroughs are the result of generating new and novel hypotheses – a skill that unfortunately, doesn’t get as much focus. Prof. William McGuire, who proposed different techniques to help generate hypotheses, laments that “our methods courses and textbooks concentrate heavily on procedures for testing hypotheses (e.g. measurement, experimental design, manipulating and controlling variables, statistical analysis, etc) and they largely ignore procedures for generating them.“

So how can you start to generate your own hypotheses? Let’s take an example. Suppose you wanted to do a science experiment that involves plants, but instead of the typical “how well do plants grown in different kinds of liquids?”, you wanted to use your own hypothesis. Here are three techniques that you could use to generate some interesting, fresh hypotheses.

- Use Analogies: Say you start with an analogy that plants are like humans. We know that humans grow faster when they are babies and then start slowing down. We can apply this fact to plants to build a hypothesis of “Do plants grow faster when they are small?”

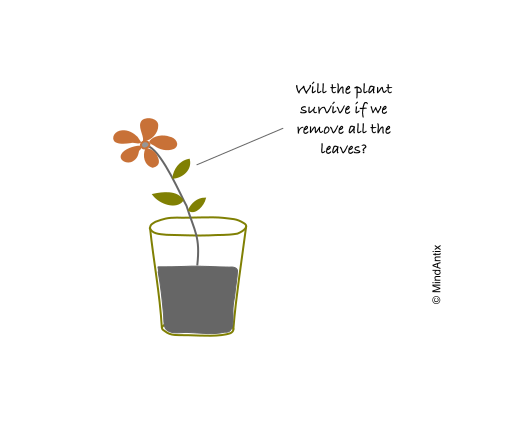

- Stretch or Shrink a Variable: We know that leaves have chlorophyll that help in photosynthesis (converting light energy into chemical energy). So one hypothesis could be that If we were to shrink the chlorophyll (maybe by removing all the leaves) would the plant be able to survive?

- Use Reversals: You can get additional insights by reversing the causality or taking the opposite of a hypothesis. For instance, if your hypothesis is that “nature lovers make better gardeners”, by reversing the causality, you get the hypothesis that “learning gardening can make you into a nature lover”. By examining and experimenting with the new hypothesis, you can potentially uncover some new insights.

As a side note, it’s worth noting that these different techniques fit well with the broader framework of creative problem solving. Using reversals or shrinking a variable are both different kinds of manipulations, while analogies use the associative process.

Every scientific advancement started with asking the right “why?” followed by the right “how?”. We can get a lot more from our science education if in addition to understanding the scientific process, we also start focusing on generating original hypotheses. As Sir Isaac Newton himself said, “No great discovery was ever made without a bold guess.”