One of the most remarkable capabilities of the human brain is its ability to categorize objects, even those that have little visual resemblance to one another. It’s easier to see that visually similar objects, like different trees, fit into a category and it’s a skill that non-human animals also possess. For example, dogs show distinct behaviors in the presence of other dogs compared to their interactions with humans, demonstrating that they can differentiate the two even if they don’t have names for them.

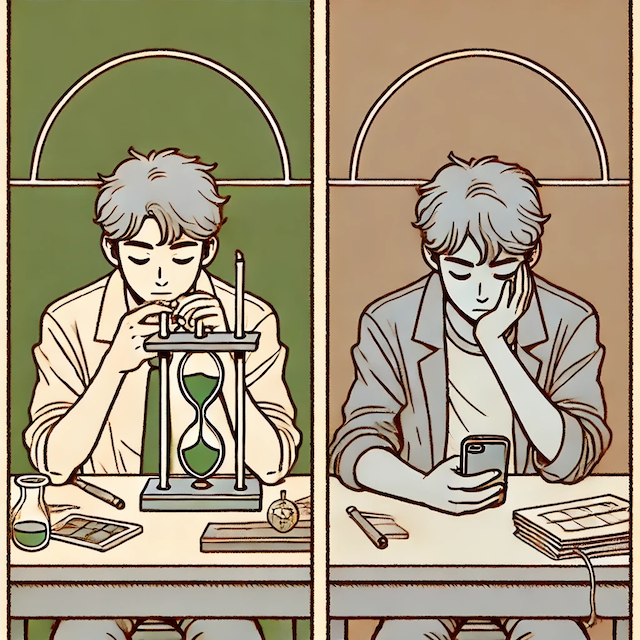

A fascinating study explored whether infants are able to form categories for different looking objects. Researchers presented ten-month-old infants with a variety of dissimilar objects, ranging from animal-like toys to cylinders adorned with colorful beads and rectangles covered in foam flowers, each accompanied by a unique, made-up name like “wug” or “dak.” Despite the objects’ visual diversity, the infants demonstrated an ability to discern patterns. When presented with objects sharing the same made-up name, regardless of their appearance, infants expected a consistent sound. Conversely, objects with different names were expected to produce different sounds. This remarkable cognitive feat in infants highlights the ability of our brains to use words as a label to categorize objects and concepts beyond visual cues.

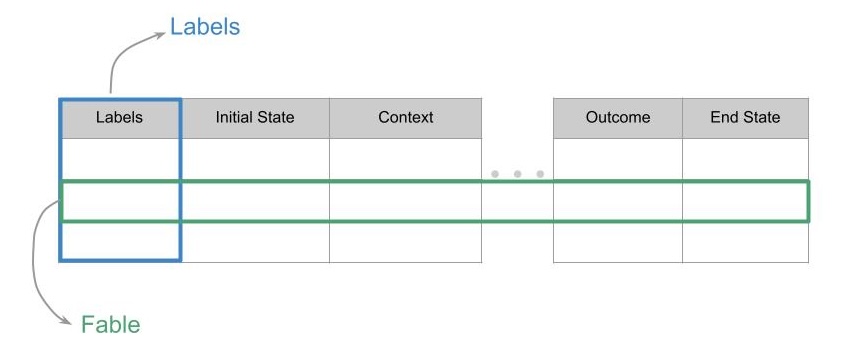

Our ability to use words as labels comes in very handy to progressively build more abstract concepts. We know that our brains look for certain patterns (that mimic a story structure) when deciding what information is useful to store in memory. Imagine that the brain is like a database table where each row captures a unique experience (let’s call it a fable). By adding additional labels to each row we make the database more powerful.

As an example, let’s suppose that you read a story to your toddler every night before bed. This time you are reading, “The Little Red Hen.” As you read the story, your child’s cortisol level rises a bit as she imagines the challenges that Little Red Hen faces when no one helps her; and as the situation resolves she feels a sense of relief. This makes it an ideal learning unit to store into her database for future reference. The story ends with the morals of working hard and helping others, so she is now able to add these labels to this row in her database. As she reads more stories, she starts labeling more rows with words like “honesty” or “courage”, abstract concepts that have no basis in physical reality. Over time, with a sufficient number of examples in her database for each concept, she has an “understanding” of what that particular concept means. Few days later when you are having a conversation with her at breakfast and the concept of “helping others” comes up, she can proudly rattle off the anecdote from the Little Red Hen.

In other words, attaching labels not only allowed her to build a sense of an abstract concept, it also made it more efficient for her brain to search for relevant examples in the database. The figure above shows a conceptual view, as a database table, of how we store useful information in our brains. The rows correspond to a unit of learning — a fable — that captures how a problem was solved in the past (through direct experience or vicariously). A problem doesn’t even have to be big – a simple gap in existing knowledge can trigger a feeling of discomfort that the brain then tries to plug. The columns in the table capture all the data that might be relevant to the situation including context, internal states and of course, labels.

Labels also play a role in emotional regulation. When children are taught more nuanced emotional words, like “annoyed” or “irritated” instead of just “angry”, they have better emotional responses. Research shows that adolescents with low emotional granularity are more prone to mental health issues like depression. One possible reason is that when you have accurately labeled rows you are able to choose actions that are more appropriate for the situation. If you only have a single label “anger” then your brain might choose an action out of proportion for a situation that is merely annoying.

At a fundamental level, barring any disability, we are very similar to each other – we have the same type of sensors, the same circuitry that allows us to predict incoming information or the same mechanisms to create entries in the table. What makes us different from each other is simply our unique set of labels and fables.