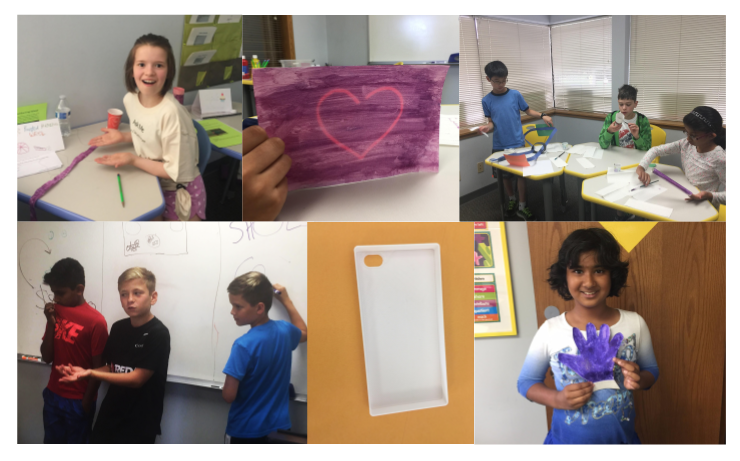

We just wrapped up our summer camps for this year and are excited to share some of the interesting inventions our students came up with! This year we collaborated once again with Archimedes school (who taught 3D printing), and explored a newer STEM area – smart materials.

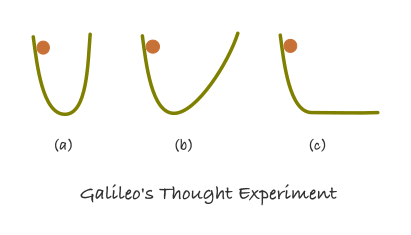

A smart material changes its physical property in reaction to its environment. The reaction could be a change in volume, color or some other material property and is triggered by a change in the environment (e.g. temperature, stress, electrical current). In other words, “…this material has built-in or intrinsic sensor(s), actuator(s) and control mechanism(s) by which it is capable of sensing a stimulus, responding to it in a predetermined manner and extent, in a short or appropriate time and reverting to its original state as soon as the stimulus is removed.”

Smart materials are being used in a lot of interesting applications including smart wearables, aerospace and environmental engineering. In our camps, we experimented with one kind of smart material – thermochromic paint, or paint that changes color with temperature. Some common examples of products that use thermochromic paints are mood rings and baby spoons.

Thermochromic paints use liquid crystals or leuco dye technology. After absorbing a certain amount of light or heat, the molecular structure of the pigment changes in such a way that it absorbs and emits light at a different wavelength than before. After the heat source is removed, the molecular structure comes back to its original form.

In our camp, we tried out different ways to change temperature and induce color change in the pigment like body heat, friction, warm light bulbs and electrical current (with high resistance wires). After the students had a chance to play with thermochromic paints, they started the process of coming up with different applications that would benefit from thermochromism.

Students used a variation of mind-mapping, and techniques like associative thinking and challenging assumptions to come up with several different ideas that could use thermochromic paint in a meaningful way. As last year, students found that by using these creative thinking techniques they could come up with 2-3x more ideas. Then they picked a final idea (after evaluating all the ideas on different criteria) to build their prototype. Quite a few of students also 3D printed their prototype (or at least parts of the prototype) by themselves!

As we expected, student ideas were all over the map. Here is a sample of some of the ideas our campers came up with:

- Electronics: Quite a few ideas were related to overheating of electronic devices so users can take a break from their device. These include cell phone cases, stickers or attachments for laptops and gaming devices.

- Thermometers: We had a few interesting thermometers for sensing indoor, outdoor and body temperature. For instance, a soft headband to put on babies and little children that can sense when they have fever – very handy to keep track of when to give the next dose of mediation!

- Baking: One student made a flexible band that goes around baking dishes and can help you keep track when the dish has cooled down and is safe to eat from. A couple students also made multipurpose gloves that could be useful during baking or other activities.

- Outdoor Activities: Students also created some interesting products like icemakers, tents and even shoes that could warn their users when it’s getting too warm.

We also had a bunch of interesting ideas like an animal shelter/cage (to help the staff easily figure out if its getting too hot for the animal), fun outdoor sunglasses, a cover for steering wheels and cupholders.

What was most heart-warming though, was to see the sense of accomplishment in these students for coming up with their own idea, following it through with prototyping and proudly presenting it on the last day!