If you were to pick the odd one out from these three things – television, computers, finger paint – which one would it be? If you are like most people, “finger paint” would stick out as the obvious answer for you.

However, that is exactly why Professor Mitchel Resnick, Professor at MIT and creator of Scratch, thinks we shortchange computer science education. As he explains, “But until we start to think of computers more like finger paint and less like television, computers will not live up to their full potential.” Just like finger paints and unlike televisions, computers can be used for designing and creating things.

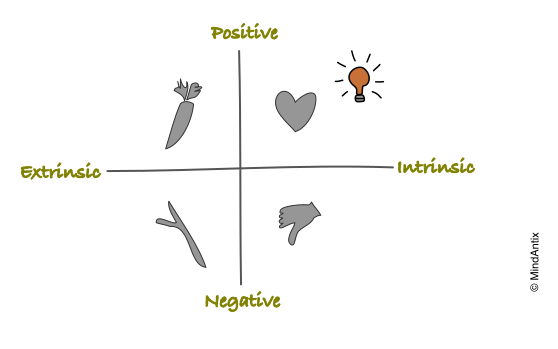

Prof. Resnick believes that the focus of education in the 21st century should be to teach children to become creative thinkers. In a paper explaining his rationale he notes, “For today’s children, nothing is more important than learning to think creatively – learning to come up with innovative solutions to the unexpected situations that will continually arise in their lives. Unfortunately, most schools are out-of-step with today’s needs: they were not designed to help students develop as creative thinkers.”

His group at MIT designed the highly popular Scratch programming environment with a “creativity first” approach. The goal of Scratch isn’t simply to teach programming constructs like loops and conditionals, but to encourage the spiraling creative process of imagine, create, play, share, reflect and imagine.

Incorporating creativity in computer science education has already shown several benefits. Researchers at a university in Ohio retooled their computer science classes to encourage more creative, hands-on learning. They found that in addition to an improvement in the quality of student work, the three year retention rate increased by 34%! This is especially important for women, who typically view computer science courses “to be overly technical, with little room for individual creativity. ”

In our latest hands-on program, “Creative Android Apps”, offered in partnership with the Archimedes School, we taught mobile app development (using MIT App Inventor) while keeping creativity a central aspect of the program. The students used several creative thinking techniques to come up with their own project to design and build. While we taught them the fundamental building blocks of programming, they went through the creative spiral process to iterate and improve their apps.

Our goal was to go beyond teaching the basics of app development to inspiring students towards computer science and STEM.

And we were truly impressed with apps that our students came up with – from managing and scheduling time, to fundraising and even an app to help others learn machine learning! But what warmed us up most were when two of our middle-school girls said “I didn’t know programming could be so much fun!” and “I felt like I was Bill Gates.”

We hope these students continue their journey towards learning and creating, and we look forward to our next Bill Gates!