Students today spend more time on academic learning than generations before. They cover more ground – learning things like programming or environmental science that their parents didn’t have to fret about – and spend more hours doing homework after school. One study found that in the sixteen-year period from 1981 to 1997, there was a 25% decrease in time spent playing outside and a 145% increase in time spent doing homework.

As our society advances even more, students will have to cover more and more content, not just during their K1-2 school years but throughout their careers. By some estimates, students growing up today will have to learn entirely new domains and reinvent their careers every few years. Learning is no longer limited to younger ages but is becoming a lifelong journey.

What does this really imply?

Students have to learn to learn – acquire knowledge and master concepts faster – without which they will find it harder to stay abreast of new developments coming their way. But it’s not just about superficially memorizing things. Students will have to understand how to apply their newfound knowledge to problem-solving. In other words, learning has to become a more efficient process in terms of speed, depth, and understanding.

Thankfully, advances in neuroscience are giving us clues on how to make learning more efficient. Understanding how the brain processes information can help students take charge of their own learning, not just in their student years but throughout their life.

Neuroscience Of How Our Brain Learns

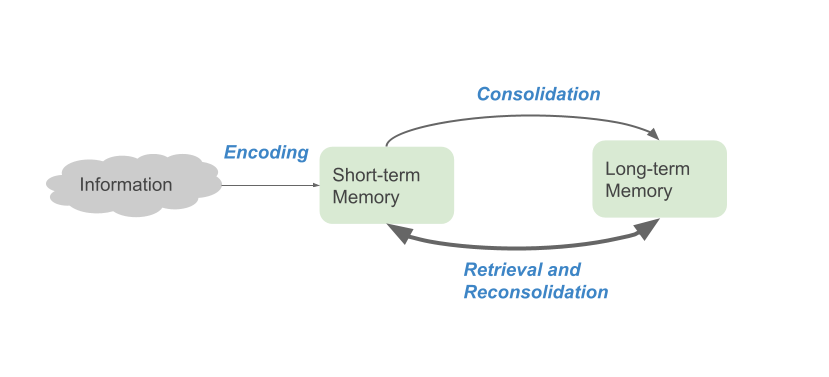

At a high level, we can view learning as a three-step process. When we encounter any new information, our brain first encodes this information and places it in short-term memory. For example, if you come across a new fact, say learning about a new breed of dog, the information first goes into your short-term memory. The next day, you might recall that your childhood friend had a similar-looking dog, and now you start to remember other details about the dog – how friendly it was, how it played, and so on.

At this stage, your memory is in long-term storage; it continuously consolidates other pieces of information that you already had. Over time you might add more connections to this piece of information, maybe a joke you heard about it, and it starts to get more and more enmeshed with other pieces of memory.

After a few days, you might forget the name of the breed and try to recall it. You struggle a bit and then remember your friend’s dog, the joke, and other bits of memory that were tied to it. And then the name suddenly comes back to you, and you get a sudden burst of relief!

A few days later, as you share a story about your childhood friend, her dog and the name of the breed come to your mind effortlessly, and you marvel at how well you remember this now.

The picture above encapsulates how our memory works. Once we consolidate information into our long-term memory, subsequent retrieval and reconsolidation help to strengthen the memory traces and make it easier to recall information in the future.

Forgetting Is The Path To Learning

Over the last couple of decades, neuroscientists have discovered interesting things about how our memory works, and counterintuitive as it sounds, forgetting information is an important aspect of remembering! Our brain is constantly pruning information that it thinks it doesn’t need so that it can serve the really important bits of information faster.

Imagine if your brain stored every little nugget of information that it receives – the color of the shirt a passenger wore in the subway, or the name of the street your friend in another state lives on – it would make it much harder to find the useful information that you really need. So if you don’t need any piece of information, its retrieval strength starts to get weaker. However, when you try to recall something that you have forgotten, i.e., when you have to struggle a bit to remember it, that’s when the brain gets a cue that this particular memory is important and might be needed again.

So, with the process of retrieval, it starts to reconsolidate the information – find newer connections to other traces of memory so the memory is stored more strongly. As a result, this process of forgetting and remembering actually helps you learn better.

Neuroscience-based memory models give us clues on how to structure our learning for maximum effectiveness. Here are three ways to boost your learning.

Repurpose Failure

When students don’t remember or don’t apply concepts correctly, it’s a sign that the information has been stored weakly in the brain. However, instead of feeling that they are ‘not cut out’ for this kind of work, students need to understand that their failure is simply a sign for their brain to reconfigure and become more efficient. Human brains are designed to learn through mistakes, so it makes sense to reframe forgetting as what it really is – a trigger that tells us that we need to take additional steps to ensure learning is complete. Students should use the opportunity to review concepts again and try to reconcile the mistakes so their understanding of the subject increases.

Adopt Active Learning Strategies & Neuroscience

Adding some challenge to the learning process that taps our brain’s natural mechanisms to process, store and understand information can significantly boost learning. Such challenges are ‘desirable difficulties’ because they make learning more efficient. Here are a few strategies that students and teachers can adopt:

- Retrieval Practice: When learning new information, periodically quiz yourself about the central ideas and new terms encountered without looking at the text. This forces your brain to fetch the answers from long-term memory, and repeated retrieval is going to strengthen your memory.

- Spaced Learning: To add more desirable difficulty to learning, practice retrievals after a period of time. When you start forgetting, you exert more effort in trying to remember, which then cues the brain to store the information more deeply. The gap between learning and retrieving can be anything from a day to a week – the key is that the gap should allow for some forgetting to happen.

- Interleaving: Instead of waiting to thoroughly master one concept before moving on to the next, try mixing up different kinds of problems or concepts once you feel you have gained sufficient understanding in one. Not only does this make good use of spacing, but it also allows you to spot connections or differences between different kinds of problems.

Research studies show that such strategies can be very effective in the classroom. In one study, students who practiced math problems in three sessions spaced apart by a week performed twice as well on the final test compared to students who did all the practice problems in one session. In another study, students performed significantly better on their science exam when a practice quiz one month before the exam interleaved concepts on the quiz.

Associative Learning & Neuroscience

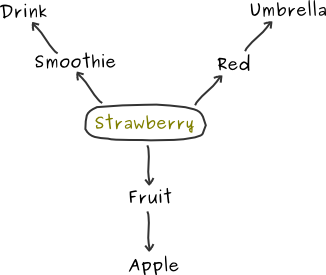

Another useful strategy in learning is to connect the information you are learning to other pieces of knowledge you already possess. If retrieval practice creates deep roots, then associative learning creates more branches that help anchor the information better. To build associative learning

- Find an analogy: Ask yourself if the new concept is similar to any other piece of information that you already possess. As an example, you might make a connection between gravity and magnetism as both involve a force that they can’t see and attract objects.

- Find a personal connection: In some cases, your personal experience can be helpful in finding connections about what you are learning. For example, while learning about the ice age, you might remember an earlier trip to Grand Coulee, where they saw how the Missoula Floods carved out a massive canyon in a very short time. The scale and impact of the event will give you an enhanced perspective of the topic and deepen your understanding.

Conclusion

By understanding the neuroscience behind learning, students can take charge of their own learning. The key to efficient learning is to add and embrace the right kind of challenges that push our brains to reconfigure themselves. Unless students lack relevant background or specific skills to make sense of the concept in front of them, such challenges should be welcomed instead of dread.

With a deeper understanding of the learning process, students can try different approaches and customize them to their needs. As an example, for some students, one day of spacing might be enough, whereas, for others, it might be a week. For the latter set, practicing a skill every day might not be as effective because they haven’t forgotten enough for reconsolidation to take place. With some trial and error, students can identify strategies that work best for them and become smart learners.

This article first appeared on edCircuit