The Programme for International Student Assessment, PISA measures students educational competence in areas like math, reading and science. Since 2000, when they first started assessments, PISA has grown in popularity and its results are eagerly awaited every three years. Part of the reason that the PISA gained so much press was that the first time PISA results came out, they took everyone by surprise.

Before PISA started testing, most people looked up to Germany and United States as models for how to run educational systems. The results, however, showed that those two countries were actually closer to the average than the top. As one policy expert expressed, “Everyone was going to the US all the time – no-one goes to the US any more to see how they do schooling… no-one thinks that the US is the international model for how to do schooling.”

The one country that started to gain recognition for it’s stellar performance was Finland. Not only did the Finnish students score near the top in all subject areas, they did it with a lot less effort. Finnish students aren’t formally tested till they are 16, barely get any homework and get more recess time than students in other countries. Since then, Finland has been a popular destination spot for everyone learning to improve schooling in their countries. So, how did Finland get to the top spot?

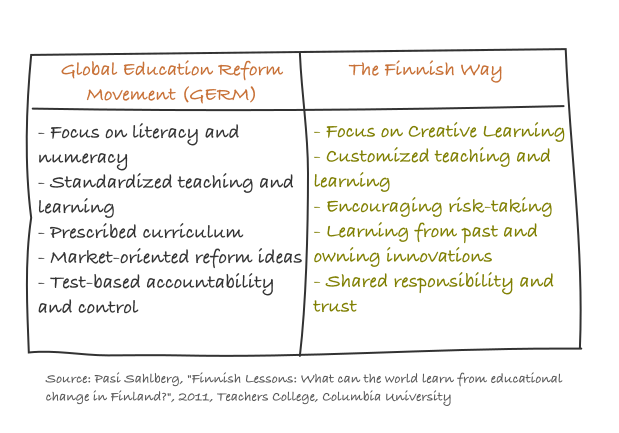

Ironically, Finland never tried to design its educational system to beat any rankings. Instead, they based their educational reform on their values of equity, hiring teachers who are highly trained and trusting them to teach effectively. Students don’t go through any standardized testing, even internally, and teachers get freedom to teach the subjects the way they like. So, when the PISA results first came out in 2000, the outcome surprised even the Finns.

In his book, “Finnish Lessons: What Can the World Learn About Educational Change in Finland?”, Pasi Sahlberg, the influential Finnish educator, gave a glimpse of their future educational directions that include problem solving, creativity, engagement and interpersonal skills. Specifically for creativity, he notes, “…students’ ability to create something valuable and new in school will be more important than ever – not just for some students, but for most of them. If creativity is defined as coming up with original ideas that have value, then creativity should be as important as literacy and treated with the same status. Finnish schools have traditionally encouraged risk-taking, creativity and innovation. These traditions need to be strengthened.”

In the latest PISA tests of 2012, Finnish students’ test scores had declined across all the subjects and the country is in the midst of their latest reform set to be in place for the 2016-17 school year. But instead of focusing solely on test scores, the latest reforms are cutting down a bit on strict numeracy and literacy to make space for other initiatives like Phenomenon Based Learning, which emphasize 21st century skills like collaboration, creativity and problem solving.

Using a narrow set of test scores to evaluate educational systems, isn’t necessarily the best model as pointed out by critics in their open letter to the organizers of PISA. The race to improve national scores has pushed more countries towards adopting standardized testing and consequently, teaching to the test. Given the changing job market that prioritizes creative problem solving, it seems less likely that students coached with this approach will thrive.

The more holistic approach to education that is currently being undertaken by Finland certainly seems promising in that light. So maybe in a few years, we will be looking up to Finland once again for their latest lessons.