One of the most potent techniques in creative problem solving, and perhaps also the most difficult, is holding two contradictory points of view at the same time. Albert Rothenberg, who extensively studied Nobel Laureates and other eminent people, found that the ability of “actively conceiving multiple opposites or antitheses simultaneously” underlies many creative accomplishments. He coined the term “Janusian” thinking after the Roman god, Janus, who has two faces that look in opposite directions.

A salient example of Janusian thinking, one that laid the foundation of quantum mechanics, is wave-particle duality. The nature of light had been a topic of vigorous debate because different experiments revealed contradictory aspects. Diffraction indicated a wave like nature while photoelectric effect pointed to its particle characteristic. It took Niels Bohr, Danish physicist and winner of the 1922 Nobel prize in physics, to resolve this apparent contradiction. More than four decades before Rothenberg came up with Janusian thinking, Niels Bohr had arrived at the concept of complementarity during a ski vacation in Norway. The key idea behind complementarity is that objects have certain complementary properties that cannot be observed or measured simultaneously, with Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle being the most well known example. So depending on the measurement apparatus, you could either get a wave like behavior or a particle like behavior. Yet, both those behaviors are equally valid and together they provide a fuller picture of reality.

The true nature of light, according to Bohr, is impossible to visualize because mathematically speaking, it requires more dimensions to represent than the three dimensions of the cartesian world. Even Einstein, who predominantly relied on visualization for his creative breakthroughs, found the juxtaposition of these two conflicting ideas too jarring. Along with Podolsky and Rosen, he offered a rebuttal to the quantum mechanical description but unfortunately it couldn’t stand up to Bohr’s complementarity argument.

A vital aspect of Janusian thinking, that Bohr brought to light, is the idea of additional dimensions. Imagine you and a friend are looking at a can of soup on a table. Your friend sees the top of the can and insists that the object is circular, while you see the side and believe it’s rectangular. As is obvious, without including the third dimension both of you cannot recognize the object as a cylinder. Finding the hidden dimension or underlying aspect is key to resolving Janusian contradictions.

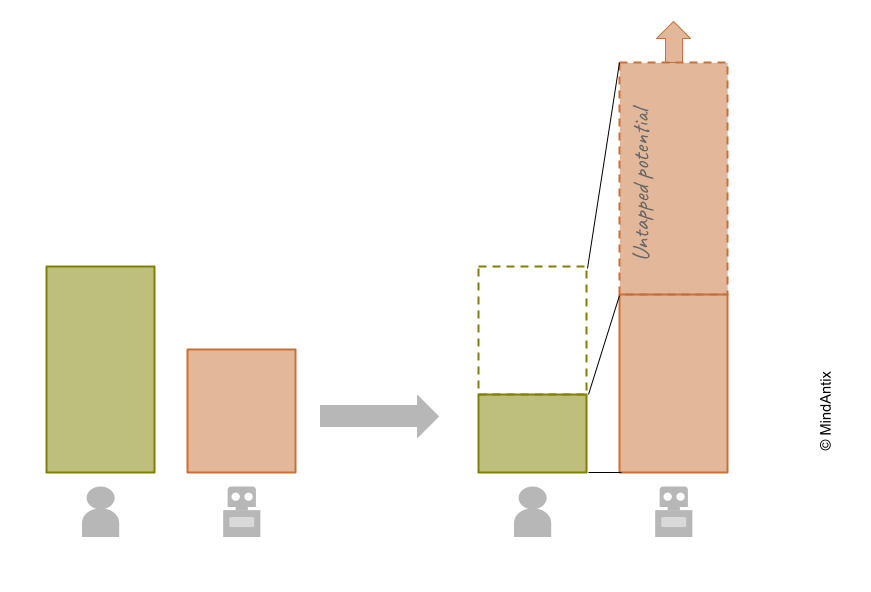

One reason why most people find Janusian thinking hard, is that holding two conflicting concepts simultaneously leads to cognitive dissonance. Our brains naturally rush to alleviate the feeling of discomfort that cognitive dissonance brings by resolving the contradiction as quickly as possible. Unfortunately, it often takes the easy way out by “picking a winner” based on an easily available argument instead of trying to view the conflicting ideas as truly complementary and finding hidden factors to resolve contradictions.

You don’t need to be a nuclear physicist to find Janusian thinking useful. Niels Bohr, who also had strong philosophical leanings, found complementarity to be a foundational aspect of life. Much like yin and yang, he saw complementarity in thoughts and feelings, instinct and reason, and different cultures. Thinking about a feeling makes the feeling disappear, and while thoughts and feelings may not be observable at the same time, they represent valuable facets of human behavior.

Bohr’s way of thinking is just as valuable in today’s world as it was back then. Here are three ways Janusian thinking can help businesses:

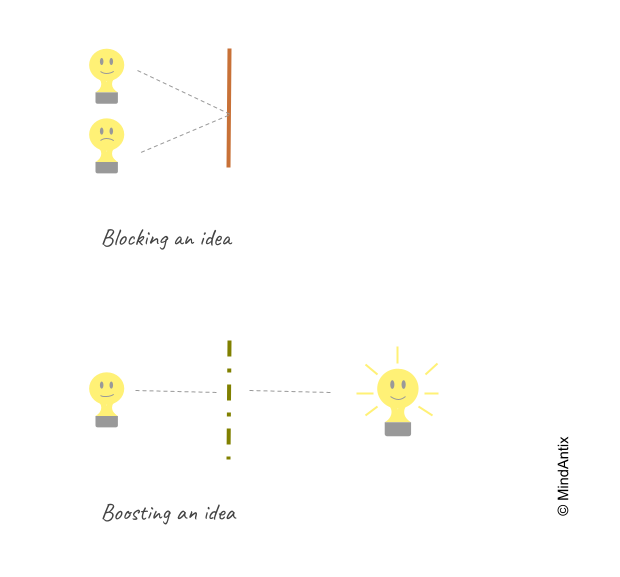

- Creative Problem Solving: The most obvious area that benefits from Janusian thinking is in creative problem solving. Engineering problems often involve tradeoffs between different factors – improving one lowers another. Janussian thinking can cut through the Gordian knot by solving the problem on a different plane. Creativity expert Michael Mikhalko shares an example from foundries that use sandblasting to clean parts. To clean thoroughly, particles need to be “hard” but hard particles also get stuck and are difficult to remove. So the paradox is that you need something that can be both hard and soft. One clever solution is to use particles of dry ice that are hard enough to clean and then evaporate. In this case, by adding a new dimension of temperature, which transforms the material, the problem gets solved at a completely different level.

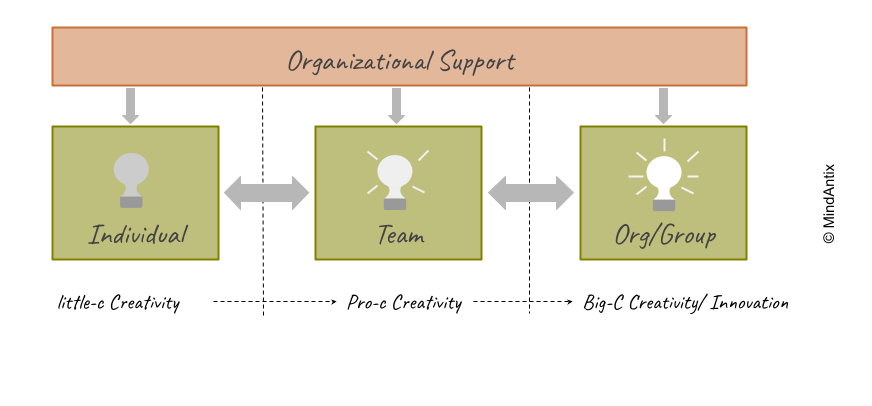

- Conflict Resolution: Applying Janusian thinking in resolving conflicts aligns naturally with transformational leadership. Leaders routinely face conflicting information – one team believes a particular feature will be a hit with users while the other team feels the exact opposite. Instead of jumping in to make a quick decision, adopting a mindset that both teams have a valid rationale naturally leads you to ask more questions and dig deeper to find underlying factors at play. Once those factors are surfaced, the conversation shifts into a more productive state – the group arrives at a more complete mental model and actively engages in discovering new pathways to make progress.

- Building Effective Teams: Bohr believed that different cultures represent a “harmonious balance of traditional conventions” that reflect the richness of human life. This lesson has even more relevance today when companies have to appeal to global audiences. A travel booking site found that German users were less likely to book compared to Danish people. On investigating further they realized that cultural differences were at play. Germans have a high threshold for uncertainty avoidance compared to their Danish peers, so showing them more details about the trip improved booking rate. Having a more diverse team ensures that decisions in product design are more creative and effective. Leaders who recognize the complementary nature of cultures choose more diverse teams not because there is a mandate to do so, but because it leads to superior results.

Holding two contradictory thoughts in your head is a challenging cognitive process, but it can yield groundbreaking ideas. There are plenty of situations ranging from product design to resolving disagreements where such thinking can lead to new insights. The next time you face a seemingly intractable conflict, apply Janusian thinking to discover a deep insight because as Bohr quipped, “The opposite of a correct statement is a false statement, but the opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth.”