When you say improv, most people think of the hugely popular show, “Whose Line Is It Anyway?” Watching how Colin, Ryan and Wayne, effortlessly create brilliant sketches and songs, can make the idea of using improv in classroom quite intimidating.

Which is ironic, since improv actually started off as exercises for young students!

Viola Spolin, considered to be the mother of improvisational theater, was an educator who developed a lot of the games that are now used in improv, for her students. Her goal was not just to teach students theater techniques, but to make them more spontaneous and draw out their creativity. She believed that students learn best by direct experience and she evaluated students as a group in a non-judgemental way, giving them the safety and space to learn by themselves. Much like what Project Based Learning (PBL) aims to accomplish now.

Working with children from low-income neighborhoods, many of whom didn’t speak English, Viola invented these games that could reach across language and cultural barriers. Her inspiration came from Neva Boyd, another educator who she had closely collaborated with earlier, who said, “Play involves social values, as does no other behavior. The spirit of play develops social adaptability, ethics, mental and emotional control, and imagination.”

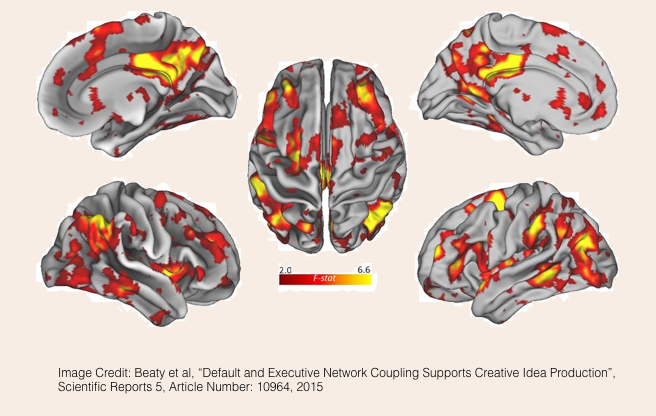

In more recent times, improv has seen an upswing outside of theater in educational and business settings. Several research studies have confirmed the benefits on using improv in building teamwork and creativity. Using an improv mind-set for case discussions in business classes led to more collaboration among team members and more creative solutions. In addition, improv exercises build confidence and reduce the fear of failure. Ronald Berk, Professor at the University of John Hopkins, who advocates the use of improv as a teaching tool, comments, “All students get to express themselves creatively, to play together, to have their ideas honored, and to have their mistakes forgiven.”

We routinely use improv games as warm-up exercises in our programs and find that they build more engagement, improve teamwork and set a more fun tone that is conducive for creative thinking. If you are curious about trying improv in your classroom, here are a few tips to get you started.

Start Simple

The main obstacle in starting improv is the fear of doing it. So the first step is to explain to students that improv isn’t necessarily about being witty or funny – it’s about keeping a conversation going. In fact, if someone focuses too much on being funny, the overall sketch often falls flat. Then start with some simple games that involve creating extended scenes but focus on building specific skills that don’t put too much pressure on students.

Some good exercises to start with are Storytelling, One Word at a Time (where students sit in a circle and create a story together with each student just saying one word to keep the story going), Fortunately/Unfortunately (where the group again tells a story but students alternate starting their sentence with “Fortunately” of “Unfortunately”), or Presents (where a student gives a box of present to another and the student receiving the present opens and declares what is in it).

Introduce Improv Concepts Early On

One of the key benefits of using improv is that the improv rules force behaviors that build collaborative and teamwork skills. The most important of these rules are:

- “Yes, And”: The “Yes, And” rule is all about accepting what someone has said and building on it. For instance, if one student says, “Why do you have a banana on your head?”, their teammate can’t say, “I don’t have a banana on my head”. Instead, she could say, “Oh, that’s my hat for the royal wedding” or if she doesn’t want anything on her head, she could just say, “Oops, I forgot to take it off” and move on with the scene. When applied to the other kinds of teamwork, it’s clear that “Yes, And” encourages team members to listen, incorporate and build on each others’ ideas.

- Deny, Order, Repeat or Question (DORQ): These are things that should not be done in an improv scene. When a student denies a reality that someone created, it violates the “Yes, And” rule. When they order someone else in a scene, they take away the other person’s ability to be creative in the moment. Repeating something that someone else says, ends up wasting time and not moving the scene forward (it’s essentially saying “Yes” without the “And”). Similarly, posing a question puts the onus on others to find a way out of the situation. All of these guidelines are also useful in improving productivity and psychological safety in any other kind of group discussion as well.

- Make Your Team Look Good: One of most fundamental rules of improv is to treat everyone on the team like a genius. If a team member says something that doesn’t sound too interesting, but others treat it as brilliant and run with it, it often turns out to be brilliant in the end. When everyone in a team treats the others like they are geniuses, back each other up, the dynamics and outcome that result are so inspiring to watch!

Weave Into The Curriculum

Once students understand the basic tenets of improv and have some practice, you could include improv games into what students are already learning for a more fun and engaging session. For instance, if you reading a novel in the class you could create some fun twists to the story (by changing an event or character) and each group could find a different way to take the story forward.

Patience and Practice

While improv is easy to introduce to students and the underlying concepts are fairly simple, becoming good at improv takes time. In the beginning, students make mistakes in their scenes where they violate one or more improv rules. A quick debrief at the end can be useful in understanding what went wrong and what they could have done instead. Other students might be too shy to start right off and need some time before they feel comfortable. But with some time and practice, it becomes a lot easier. Students start internalizing the improv rules and their teamwork skills start spilling out into other areas.