Why does the Narwhal have a spiral in its tusk? While many people had wondered about this, the most rational explanation came from D’Arcy Thompson, Scottish biologist and mathematician.

Thompson’s explanation for the spiral was that each stroke of the narwhal’s tail produced not just a forward motion but also a twist that made the narwhal go slowly around it’s own horn. While some of Thompson’s theories were proven wrong, he found many interesting reasons for different shapes and forms in nature. His book, On Growth and Form, laid the foundation for the field of morphogenesis, the process by which body structures are formed.

One of the reasons that Thompson was able to find interesting patterns in nature, was because of his ability to abstract simpler elements from the form of an animal or plant. As Stephen Jay Gould, who was inspired by Thompson’s work, explains “he tried to explain form by reducing its complexity to simpler elements that could be identified as cause.” In other words, his abstraction abilities helped him understand the underlying causes of different forms in nature.

So, what is abstract thinking? There are two aspects of abstract thinking – simplifying by removing details to find salient features, and generalizing to find the core essence. The ability for abstract thinking underlies creative and complex problem solving in many different domains.

Jeff Kramer, Professor of Computer Science, noticed over his 30 years of teaching that some students were able to handle complexity better than others. They were able to understand distributed algorithms more easily and produced more elegant models and designs. In his words, “What is it that makes the good students so able? What is lacking in the weaker ones? Is it some aspect of intelligence? I believe the key lies in abstraction: The ability to perform abstract thinking and to exhibit abstraction skills.”

The ability to abstract plays a key role in creative problem solving as well. Tina Seelig, Professor at Stanford University and author of InGenius, notes that reframing a problem by asking “why?” can open up a whole new set of solutions. For example, by reframing “How should we plan a birthday party?” to “How do we make this a special day?” can open up a whole new set of possible ideas.

Reframing a problem typically involves moving to a higher (or more general) level of abstraction. Two ways to reach a higher level of abstraction is to ask ‘why’ or find a category that a given concept belongs to.

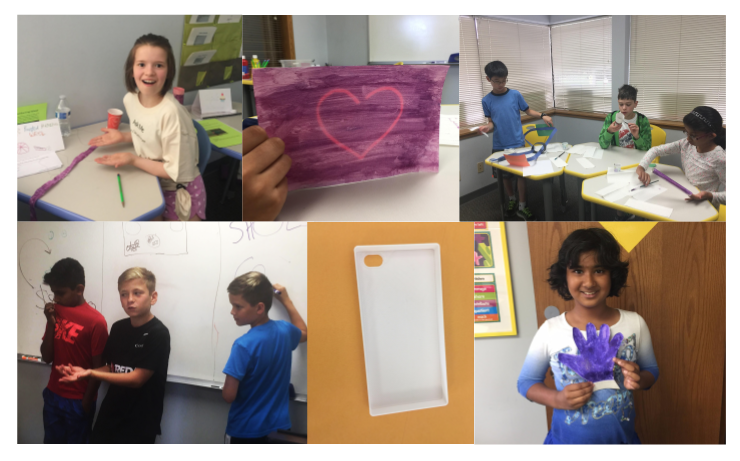

We created our new brainteaser, ‘High and Low‘ to build the ability for abstract thinking and make students comfortable with navigating different levels of abstraction. The brainteasers give a routine activity and the goal is to find one or more ‘High’ and ‘Low’ levels for the activity. The ‘High’ level corresponds to the more general level of abstraction while the ‘Low’ level corresponds to the more specific one.

Liberman and Trope, describe how the high and low level descriptions can fit into a pattern, “superordinate, high-level descriptions of an activity fit the structure “[description] by [activity]” whereas subordinate low-level descriptions fit the structure “[activity] by [description]”.” For example, if the activity is ‘reading a book’, a high-level description could be ‘learn new things’ (I [learn new things] by [reading a book]) while a low-level description could be ‘by flipping pages’ (I [read a book] by [flipping pages]).

Our goal with these brainteasers is to build this crucial skill of abstract thinking early on through simple exercises. In a recent trial, we were excited to see 8-9 year old students solving these exercises appropriately and being able to apply abstract thinking in reframing problems. We hope that by starting to use abstract thinking in different areas, students will be able to handle complex problem solving more easily later in any domain.