What’s the best way to spread butter on toast? It turns out that people have pondered this problem at length and have come up with many solutions, including a recently funded Kickstarter project for a ButterUp Knife . But did you know about this little known “invention”, Butterstick – butter that comes in a stick just like a glue stick or a lipstick? You simply twist the bottom and start applying the butter – simple, easy and no dirty knives!

The inventor of Butter Stick and hundreds of other such creative inventions is Kenji Kawakami, the progenitor of Chindogu, the Japanese art of “unuseless” inventions. The word Chindogu, translates to “strange tools” or tools that seemingly solve a problem, but as Kawakami explains, “chindogu have greater disadvantages than precursor products, so people can’t sell them. They’re invention dropouts.“ Nevertheless, Kawakami finds making Chindogu “an intellectual game to stimulate anarchic minds” and pursues this art with an almost spiritual devotion.

The art of Chindogu has spread all over the world since Kawakami created it in the late 1980s. Tina Seelig, professor at Stanford University and author of InGenius: A Crash Course in Creativity, considers Chindogu to be an indispensable tool to spur innovative thinking (the Imagination component in her Innovation Engine model) and routinely uses it in her courses. Chindogu, as Dr. Seelig describes, is about “putting things together in surprising ways – they are not useful, they are not useless but when you put them together interesting things happen.”

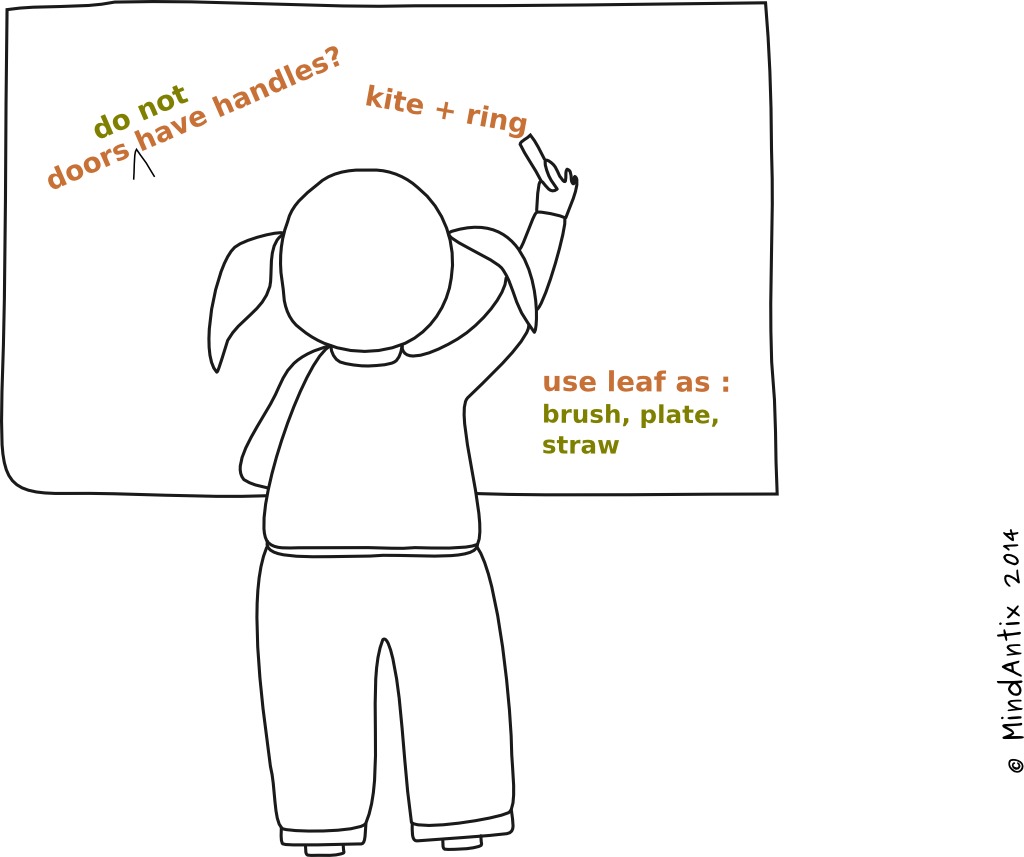

Chindogu is the inspiration behind the MindAntix brainteasers, “Wacky Inventions”. But there is a twist – instead of identifying a problem and then building a gadget to solve the problem, you have to combine the two random objects in the brainteaser in a meaningful way to solve some problem.

At a recent Creative Thinking session, I gave a group of 4th and 5th graders an additional task – not only did they have to make an invention using two random objects, they also had to make an infomercial to sell their neat gadget to their classmates! It didn’t take long for the creative juices to start flowing. We soon had impressive ideas from different teams like Jumbrella Skiing using an umbrella and a jump rope (because water skiing while standing is hard, so why not sit down and relax while you are being pulled?), and a Hold-a-Loon using a balloon and a paper clip (you never have to worry about carrying heavy books again). Not only did all teams accomplish their goal of creating something novel, they were all amazed at having created something useful out of completely random elements.

Connecting and combining ideas from different domains is the essence of creativity. Fun exercises like Wacky Inventions and Chindogu are a great way to build associative thinking skills. Nurturing such little-c and mini-c creative adventures is an essential element in paving the way for groundbreaking innovations later.