When people talk about creativity, outgoing personalities invariably come into the picture. It seems to be commonly accepted that extraverted, playful people tend to be more creative. But is that really true?

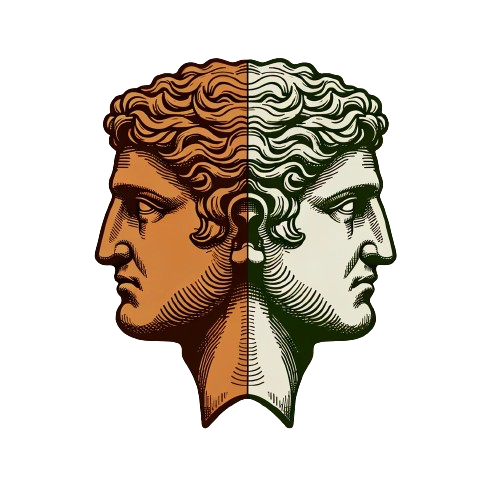

Mozart and Newton personify the boundary-pushing, Big-C Creativity in very different disciplines of music and science. They both made immeasurable contributions to their fields and inspired many others over generations to follow their footsteps. But not only were their domains vastly different, their personalities were too.

Mozart was an extrovert with a bawdy sense of humor, who loved to party, drink and play pranks. He often got into trouble due to his eccentric behavior. Newton, on the other hand, was a socially awkward introvert. He had few friends and preferred to spend time alone.

Of these two – Mozart and Newton – who do you think was more creative?

The question is obviously ridiculous. Both of them were creative giants who radically transformed their own fields. While externally they couldn’t be more different, internally they were likely much more alike.

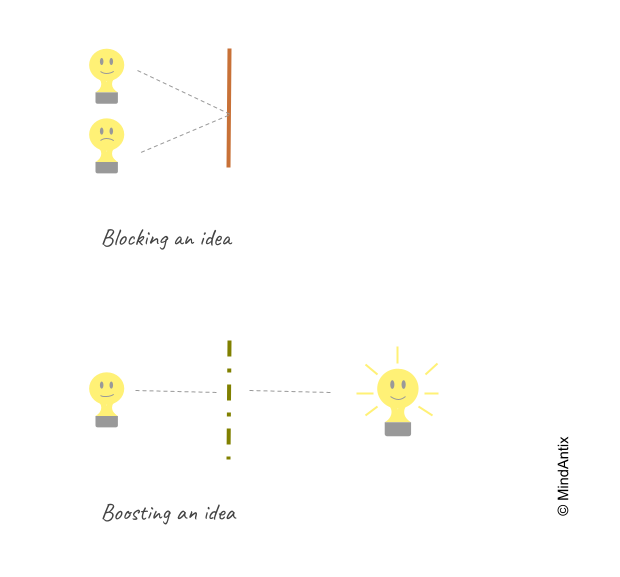

Most people mistake extroverted, playful people as being more creative but that is not necessarily true. It’s not the external playfulness that matters but the internal playfulness with ideas – something that both extroverts and introverts are capable of doing. Creativity emerges when you take ideas and perform mental transformations on them like changing boundaries or combining with other ideas, or in other words, when you playfully manipulate them. Someone could be a playful person on the surface, but without doing the internal playful work with ideas, they are not going to come up with groundbreaking ideas.

This playfulness with ideas is what makes Mozart and Newton similar. With Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Mozart pushed the boundaries on what an opera was expected to be at the time. He wrote it in German instead of Italian, he used an unexpected and controversial setting of a Turkish harem, and the opera incorporated elements of Turkish music. Those were controversial ideas at the time but eventually the opera became a huge success. Similarly, in his cannonball thought experiment, Newton pushed the limit of projectile motion which allowed him to make the connection between planetary motion and objects falling on Earth. He had to simplify objects, reducing them to mathematical points to prove that the same universal law of gravitation worked for all objects. According to an anecdote, when an admirer asked Newton how he made his discoveries, he replied “By always thinking unto them.”

So, if extraversion doesn’t predict creative output, is there any other personality trait that does?

The trait of “Openness/Intellect” – one of the Big 5 personality traits – is the only trait that shows a consistent relation to creativity. A study by Kaufmann and others found that “artistic creativity draws more heavily on experiential Type 1 processes associated with Openness (e.g., perceptual, aesthetic, and implicit learning processes), whereas scientific creativity relies more heavily on Type 2 processes associated with Intellect and divergent thinking.” Incidentally, their study did find an unexpected correlation between extraversion and artistic creativity but not scientific creativity.

When companies strive to make a more creative and innovative culture, they often fall into the same trap. They focus on external things – like foosball tables or bean bags – to create a fun, playful vibe in the hope that it will lead people to think more creatively. Their interviewing and hiring processes tend to favor extroversion. But without creating an environment where offbeat ideas are encouraged, debated and experimented, groundbreaking innovation is not likely to happen. Companies might think that they encourage play but what they create is a playpen and not a playground.

Mitch Resnick, Professor and Director of the Lifelong Kindergarten group at MIT, uses the metaphor of playpen vs playground to differentiate the different kinds of play they support. A playpen might have interesting toys to play with but it is a restrictive environment with limited autonomy and freedom of exploration, whereas a playground promotes open exploration, problem solving and creativity. Needless to say, a playpen stifles creativity while a playground nurtures it.

To build more innovative cultures, companies need to hire people who are curious and open to new ideas, which isn’t related to extroversion or introversion. And then they need to create intellectually stimulating environments where people can freely play with ideas, debate them with others and explore their potential.