Imagine a common workplace hurdle: two colleagues—Alex from Sales and Priya from Marketing—are jointly preparing a spreadsheet for an upcoming quarterly business review. Late one evening, Alex revises the structure of the spreadsheet, reorders the data, and adds projections. The next morning, Priya logs in and discovers her inputs have been moved or removed. She feels her contributions have been disregarded. Alex believes he improved the document for clarity.

What starts as a simple task quickly spirals into conflict. Communication becomes strained. Collaboration deteriorates. This type of conflict is not uncommon—but how it unfolds depends significantly on the perceived nature of the relationship between the parties involved.

This scenario serves as a practical illustration of psychologist Morton Deutsch’s influential theory of cooperation and competition, a foundational framework in the field of conflict resolution.

Deutsch’s Theory of Cooperation and Competition

In the 1940s, psychologist Morton Deutsch developed a powerful framework for understanding conflict, centered on the crucial concept of interdependence—how our goals are linked to others. According to Deutsch, the way individuals perceive the relationship between their goals determines whether conflict is approached cooperatively or competitively.

He identified two types of interdependence:

- Positive: Goals of two people are linked in such a way that the probability of one person’s success in achieving the goal is positively correlated to the attainment of the other person’s goal. In other words, the two people sink or swim together.

- Negative: In a negative linkage, if one person wins the other loses.

These perceptions shape the actions individuals take in conflict situations. Actions can be effective (improving the chances of reaching a goal) or bungling (ineffective or even detrimental, worsening those chances).

When interdependence and actions interact, they give rise to three important relational dynamics that shape the tone and trajectory of conflict:

- Mutual Support (Substitutability): How much one person’s actions help or hinder another. In essence, are you working together or against each other? In a cooperative setting, effective actions by team members support each other as they contribute to a shared outcome. In a competitive setting, a bungling action by one might be helpful to the opponent as they look better in comparison. In the spreadsheet example, if Alex’s late-night edits were useful and if Priya perceived the situation as cooperative, she would see the changes as supportive.

- Openness to Influence (Inducibility): This is the willingness of individuals to listen to and be influenced by one another. When people view each other as partners, they are more likely to adapt their ideas and consider alternative perspectives. In contrast, competitive dynamics create defensiveness and resistance to input. In the spreadsheet conflict, if Priya and Alex trust each other’s intentions, they’ll likely integrate feedback and co-create a better result. If they view each other as rivals, they’ll resist collaboration and retreat to siloed efforts.

- Attitudes and Emotions: These are the feelings and judgments people hold about each other—such as trust, respect, suspicion, or resentment. Positive interdependence fosters goodwill, patience, and empathy. Negative interdependence breeds anxiety, frustration, and hostility. Over time, these emotional patterns solidify and influence the workplace culture as a whole.

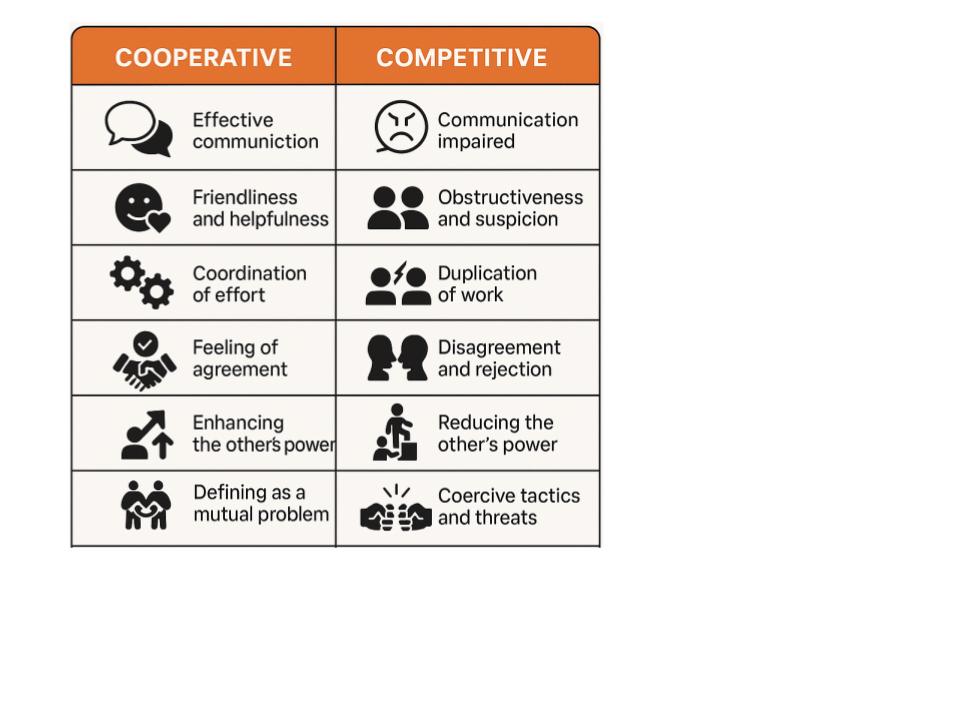

These dynamics—mutual support, openness to influence, and the feelings between team members—are constantly shifting. They’re deeply influenced by how individuals view their interdependence and the actions they take. Deutsch’s research clearly showed that when people are skilled and their actions are effective, a cooperative approach consistently leads to stronger relationships, greater trust, and ultimately, better outcomes than a competitive one.

Cooperation vs. Competition in Action

Returning to the example of the spreadsheet, let us consider two potential outcomes—one cooperative, one competitive:

Cooperative Resolution: Alex and Priya, guided by a shared understanding of their mutual goal (a successful business review), approach the situation with curiosity. Priya calmly voiced her concerns, and Alex explained his rationale. They agree to jointly review the document and integrate both sets of inputs. Their actions are effective, attitudes remain positive, and each is open to being influenced by the other’s suggestions. Substitutability is high—they both contribute to the same goal—and the relationship is strengthened. In addition, they set new norms on how to make changes to each others’ sections so as not to create confusion.

Competitive Breakdown: Priya reacts defensively, assuming Alex is trying to take over the project. Alex feels unappreciated and digs in. Communication becomes guarded, and each begins working on their own version of the report. Substitutability disappears, attitudes harden, and inducibility vanishes. The final presentation is disjointed, and leadership notices the lack of cohesion. The competitive breakdown not only damaged the report but also left lingering resentment between Alex and Priya, impacting future collaborations.

These contrasting outcomes underscore the value of Deutsch’s insights: conflict is not inherently destructive. The determining factor lies in how individuals interpret their interdependence and choose to act.

Strategies for Leaders

Leaders have a critical role to play in shaping the environment that determines whether conflicts become constructive or destructive. Below are three evidence-based strategies drawn from Deutsch’s theory:

1. Reframe Conflicts to Highlight Positive Interdependence Help team members view their goals as interconnected rather than opposed. Facilitate discussions that highlight how each team member’s contribution is essential. In the spreadsheet example, a manager could emphasize that both Sales and Marketing bring vital perspectives to the business review and that their input is complementary.

2. Design Incentives to Reinforce Cooperation Audit reward structures to ensure they do not unintentionally foster competition. Avoid systems where individuals are pitted against one another for limited recognition or rewards. Instead, design performance metrics that reward collaborative outcomes, knowledge sharing, and collective success.

3. Establish Norms and Processes for Constructive Dialogue Promote group norms that encourage respectful disagreement, active listening, and open communication. Use structured meeting formats with clear roles and turn-taking to ensure all voices are heard. Leaders should model openness to influence and reinforce norms that make it safe to express dissent without fear of reprisal.

Conclusion

Morton Deutsch’s work offers a powerful lens through which to understand and transform workplace conflict. By implementing Deutsch’s principles, leaders can transform their workplaces into hubs of collaboration and innovation. In doing so, even the most routine workplace conflicts—like a disagreement over a spreadsheet—can become opportunities for greater trust, innovation, and shared achievement.