One of the earliest people to recognize that posing questions and finding problems can be an invaluable tool in learning was Socrates. Almost 2,500 years ago, Socrates developed an approach of asking questions (elenchi) to reach a state of contradiction (aporia) to help discover new insights for the concept under study. Even though he was eventually found guilty of “corrupting the minds of the youth” and sentenced to death by drinking poison hemlock, his ideas survived and influenced the present-day scientific method.

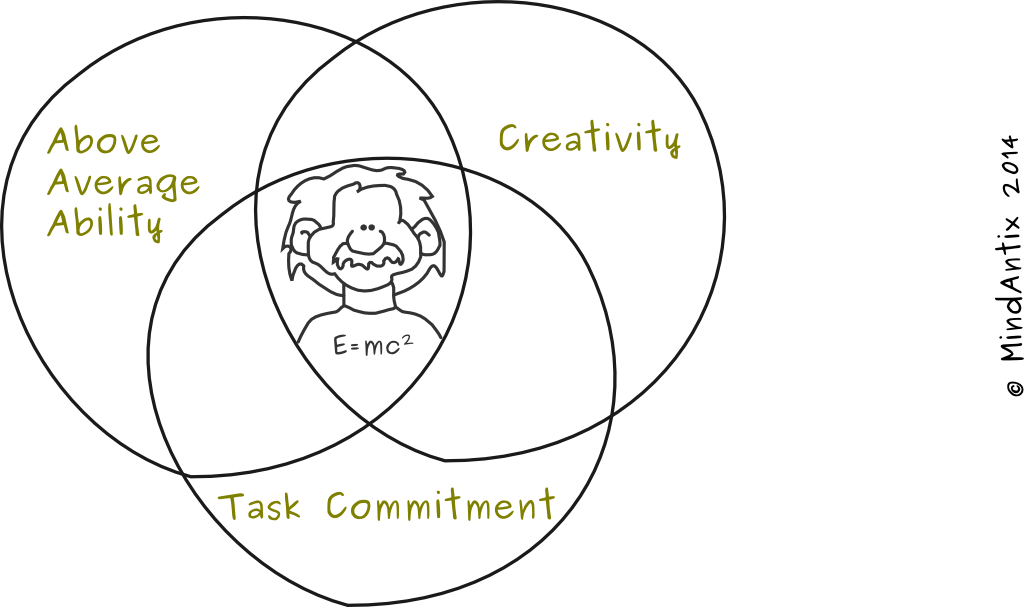

Jacob Getzels and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, leading figures in the field of creativity, have explored the role of problem discovery in creativity. In a landmark experiment, they brought in art students who were given the task of drawing still life from a selection of objects. They found that students displayed one of two behaviors – problem-solving students spent less time choosing and manipulating an object they painted, while problem-finding students spent considerably longer examining and manipulating their objects. What they learned next was quite interesting.

The problem-finding artists generated paintings that were judged to be more original by a panel of independent experts. What was even more fascinating was how these artists fared in the long run. Getzels and Csikszentmihalyi measured the success of these students seven years after the experiment and again after another eleven years. They found that problem-finding students were the most successful in their careers as artists compared to problem-solving students, many of whom had abandoned art altogether!

Problem posing isn’t just relevant in the art domain – it extends to even mathematics, a field conventionally not considered creative. In a study conducted on creativity and mathematical problem posing, researchers asked high school students in US and China to come up with as many mathematical problems in different tasks. An example task was a figure of a triangle with an inscribed circle where the participants had to make up problems related to the figure. Researchers then evaluated the responses on the fluency, flexibility and originality – key dimensions of creativity. They found that the more mathematically advanced students were also more creative in posing problems compared to their peers. Professors Singer, Ellerton and Cai, who study mathematical education in the different parts of the world, summarized as follows: “Problem posing improves students’ problem-solving skills, attitudes, and confidence in mathematics, and contributes to a broader understanding of mathematical concepts and the development of mathematical thinking”.

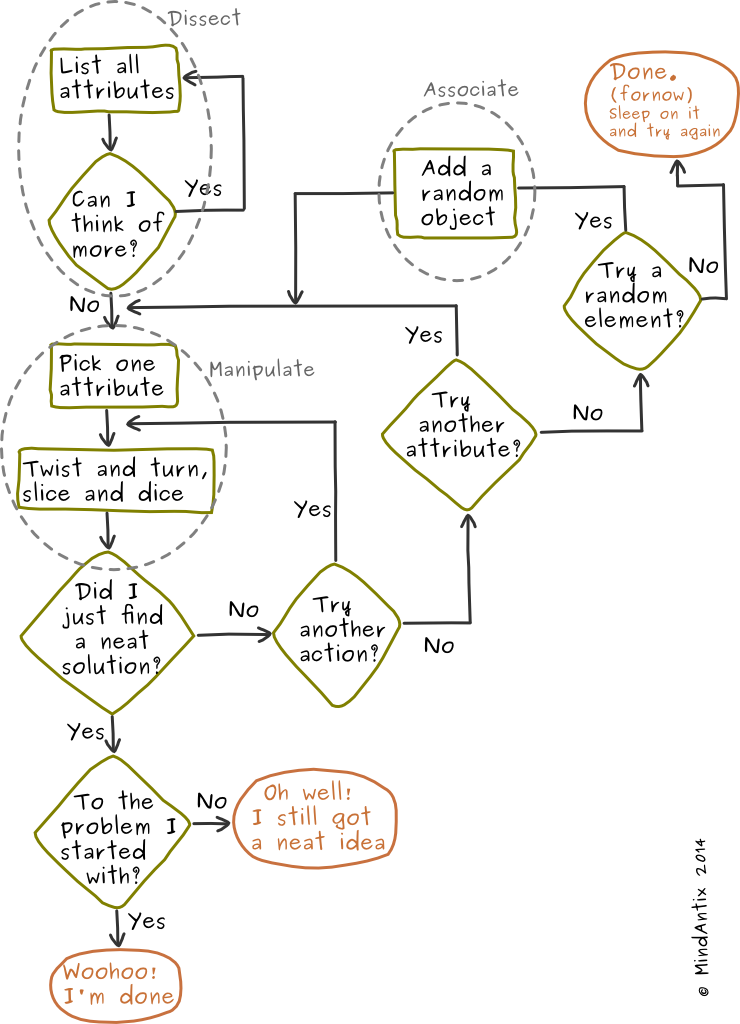

Creativity flourishes when problem finding meets problem solving. Professor Edward Silver, who conducts research related to teaching and learning of mathematics, observes, “The connection to creativity lies not so much in problem posing itself, but rather in the interplay between problem posing and problem solving. It is this interplay of formulating, attempting to solve, reformulating, and eventually solving a problem that one sees creative activity”.

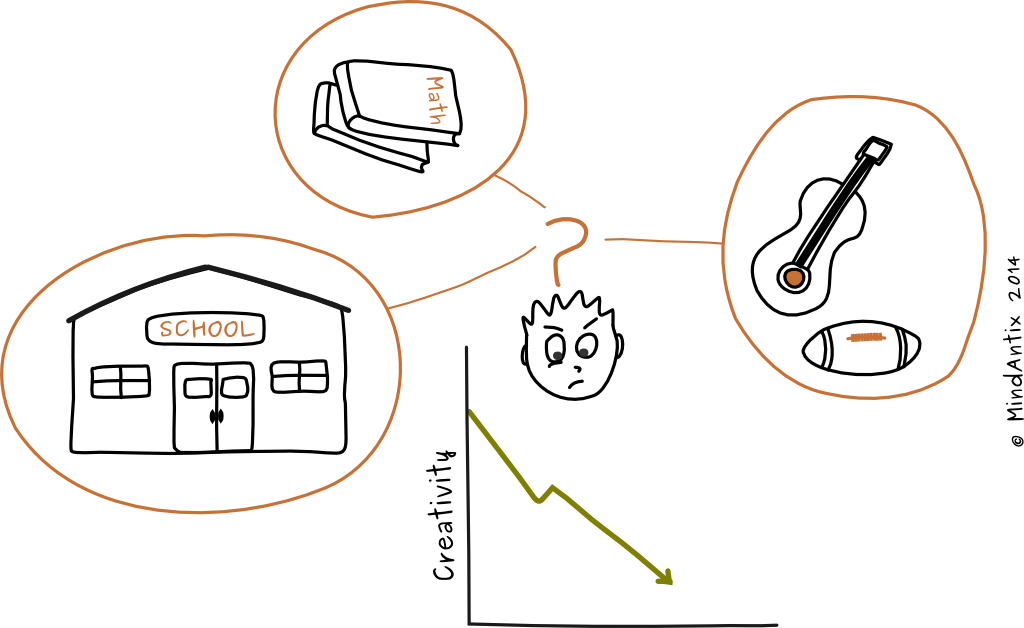

Problem finding is at the core of MindAntix – users not only solve creative problems but are encouraged to find new problems that they have observed or discovered in the process. Problem finding, while often overlooked, is a meta-skill applicable to many different domains and is an indicator of both creativity and excellence.