In 1911, Elizabeth Kenny, a nurse in Australian Outback, was called upon to take care of a little girl who she thought had infantile paralysis. She wrote to her mentor, Dr. McDonnell, for advice who wired her back with a message to treat “according to the symptoms as they present themselves.”

Not realizing that the girl really had polio, Elizabeth started finding ways to alleviate the symptoms. She noticed that the girl’s muscles were very tense, so she used hot compresses which she theorized would help relax the muscles. The girl found instant relief from the hot compresses and they reduced her muscle spasms. Next, she saw that the girl could barely move her limbs. Once again, she hypothesized that the muscles needed retraining and increased blood flow. So she started a regime of motion therapy and massage (an approach that later evolved into physical therapy). The results were dramatic and the girl recovered and was able to walk again!

In comparison, the conventional approach to treating polio at the time was to immobilize the limbs by attaching splints which pretty much ensured that patients would not be able to fully recover their mobility. Elizabeth went on to treat many more polio patients, despite being rebuffed by the medical establishment. It took the medical community several decades to acknowledge that her methods of treating polio were indeed effective.

Not knowing that she was actually treating polio, turned out to be a blessing for Elizabeth. It led her to create fresh hypotheses based on what she observed, come up with creative techniques and test them.

Most advancements in science came by because of creative leaps in generating hypotheses or designing better experiments. Creativity plays an integral role in all real-world science explorations – from problem finding to generating and testing hypotheses. As psychologists, David Klahr and Kevin Dunbar who proposed the Dual Space Search in Science approach, explain, “The successful scientist, like the successful explorer, must master two related skills: knowing where to look and understanding what is seen. The first skill – experimental design – involves the design of experimental and observational procedures. The second skill – hypothesis formation – involves the formation and evaluation of theory.”

So, how do we build some of this scientific creativity among younger students?

Research in scientific creativity can be viewed as an interaction between general creativity skills and science knowledge and skills. Here are a few simple approaches to build scientific creativity among students.

Problem Finding

Problem finding in general is considered a core aspect of creativity, and it extends to all domains including arts, math and even science. Real-world problem finding is more predictive of creative achievement than standard measures of divergent thinking.

One way to encourage problem finding in science is to have students list problems they want to explore in a science topic. For example, give students an exercise to think of as many research topics as they can, on subjects like the behavior of ants or the growth of plants. The idea is to give them a chance to think of what they already know and discover areas they want to extend their understanding in.

Hypotheses Generation

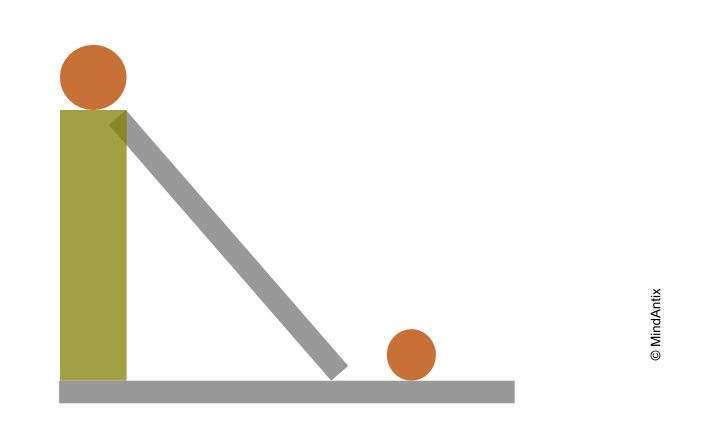

The ability to generate many alternative hypotheses is related to success in science. However, research shows that children tend to get stuck focusing on a single hypothesis. One approach to build the ability to generate multiple hypotheses is to present a partially-defined experimental scenario or setup, and ask students to generate as many hypotheses as they can. For example, give students an adjustable ramp and different balls as the setup to explore connections between different variables like height, weight, speed and time. That could lead to hypotheses around what happens when you roll different weight balls or change the height of the ramp and so on.

Scientific Imagination

Scientific imagination is one of the key aspects in the scientific creativity model proposed by Hu and Adey. Einstein had often mentioned how imagining himself chasing a beam of light gave him the insights that eventually led to the development of special relativity. The role of such imagination in science, which is different from creative imagination, is now considered valuable.

One way to build scientific imagination is to give students story writing tasks on topics like “what if there was no gravity” or “the sun is losing its light”. The goal isn’t to just write an imaginative story but to get students to use their scientific knowledge to guide their story.