Analogies are tricky. They can suddenly illuminate a hidden facet and bring to light new insights, new ideas and new solutions. But just as often, they push you to think in a single direction, that when taken too far, causes more harm than good.

One analogy that is surfacing again is that of wartime and peacetime CEOs. Now that many companies are facing existential crises, there are calls to move away from a peacetime mode and bring a more wartime mentality to doing business. But this is a false choice. Companies are not at war (yes, they have to compete but that’s different) or at peace – instead, their primary task is to continuously innovate and stay relevant.

The reason that this particular analogy is dangerous is that a warlike approach – think of a general directing orders, employing (mostly) sticks and (sometimes) carrots to get his troops to perform – is the exact opposite of what is needed for true innovation to take place on a regular basis. To be fair, the analogy works at times because it has some truth to it. But every analogy has its limitations. A wartime approach works in narrow situations for short periods of time, but making it the default mode of operation in an environment where high levels of innovation are the only solution to stay alive can only cause long-term damage.

The Two Beasts: Innovation and Productivity

Every company has to do innovative work as well as routine or productive work. For example, deciding what new product or feature to release that is both novel and solves an important customer problem is innovative work. With the innovative idea finalized and the workability of the novel aspect determined, implementing it becomes more of a routine/productive work. Even though both kinds of work require problem solving (barring some of the most mundane routine tasks), they are of very different nature. While most people think of creativity as a fun, relaxing activity, in reality it is more cognitively demanding compared to critical or logical thinking.

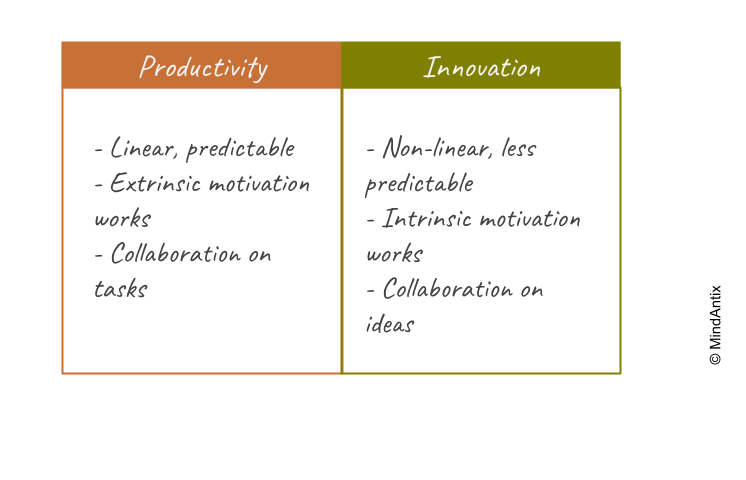

Productive work is much more linear and therefore predictable in nature, making it easier to plan and track. In contrast, innovative work is much more non-linear, it requires multiple iterations and carries larger risks. While project management tools can handle productive work well, innovation management needs a very different type of tool to capture its underlying risk and complexity.

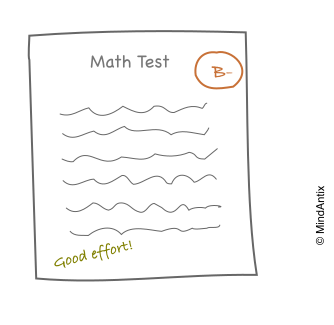

Incentives also work differently for the two kinds of work. External motivators (like monetary rewards or threat of layoffs) can improve performance of routine tasks but can backfire for creative work in some situations. When people are nudged to adopt an extrinsic orientation or expect to be rewarded for a task, they produce less creative work.

And finally, even though both kinds of work require collaboration, the nature of collaboration is different. For routine/productive work, collaboration is primarily coordination of tasks – tracking individual tasks and dependencies between different tasks and people. Creative work, on the other hand, requires collaboration of ideas – different ideas clashing together to create something much more interesting. In other words, even the day to day work that people engage in, including the kinds of things people talk about in meetings, is vastly different for innovative and productive work.

Innovative and productive work are both equally essential for a company. However, they are two very different beasts and the real challenge comes in managing both without compromising either.

When productivity metrics are applied to innovative work, as often happens in the corporate environment, a natural and predictable consequence is for innovation levels to drop. If you are tasked with a feature and your success is tracked through completion deadlines, there really is no option for you other than to pick the safest and simplest implementation that allows you to show up “green” on the project dashboard. Risk averseness starts to creep in at every level from padding estimates to reducing complexity, and innovation, which by its very nature involves high risk, is suppressed.

Or, when companies implement some form of “rank and yank” system, idea collaboration among employees drops. If you are forced to compete with the person sitting next to you, it doesn’t make sense for you to collaborate and share credit if you believe you have a winning idea. An idea that could have bloomed with new perspectives, remains stunted. People become more focused on protecting their turf, leading to more politics and again, less innovation.

If you think that hiring the smartest people would circumvent this problem, you would be mistaken. The underlying currents of human motivation and self-preservation are far too strong for things to go any other way. Most people eventually learn to adapt to the system and those who can’t or don’t want to, get frustrated and leave.

The challenge for any company is to manage both these processes successfully, and neither the wartime nor peacetime approach is adequate.

How The Manhattan Project Managed Radical Innovation

One of the most interesting examples to have successfully tamed the two beasts to produce groundbreaking work was the Manhattan Project, which produced the first nuclear weapons. To understand how impressive this accomplishment was consider the following:

- The Manhattan project started modestly but grew to about 130,000 people in just a few years, spread across multiple locations.

- The team faced huge scientific and technical challenges – prior research on producing fissionable was very preliminary and had many gaps. Processes that were eventually adopted, either did not exist before the project or had never been used with radioactive materials before.

- Fears that the German nuclear research team would produce the first atomic bomb created a strong time pressure. Fundamental research, and the design and building of the plant had to be done concurrently, something that had never been done before.

These and other issues placed considerable management stress from scaling the team to shipping a challenging product on an accelerated schedule. So, how did the Manhattan project pull off such a feat?

To start, Leslie Richard Groves, the general in charge of the overall project, had the foresight to recognize that the typical command-and-control management style would not yield the required levels of innovation and there was no existing playbook to go by. Despite being in the middle of an actual war, he took a decidedly “un-wartime” approach to management. He first hired J. Robert Oppenheimer, a well respected theoretical physicist at UC Berkeley, as his counterpart to work with the scientists and researchers. Effectively working as co-CEOs, they found new ways of managing people and work in order to accomplish their audacious goals.

And they faced massive challenges from the get go. For example, when Groves asked scientists how much fissionable material would be needed for each bomb, he expected an estimate within 20%-50% and was horrified when he got a factor of ten! He quipped, “My position could well be compared with that of a caterer who is told he must be prepared to serve anywhere between ten and a thousand guests. But after extensive discussion of this point, I concluded that it simply was not possible then to arrive at a more precise answer.”

Faced with such high levels of uncertainties, Oppenheimer and Groves realized that they will have to pursue multiple solutions at the same time. Given the time constraint, they decided to explore all options in parallel both for producing fissionable material and for gun design. They spun off multiple teams to explore different alternatives, and plant design proceeded under the assumption that any or all of these approaches would be needed. As research progressed, Oppenheimer realized that some of the processes could be combined for higher efficiency, a lucky turn of events that wouldn’t have happened without the parallel approach!

Managing Innovation

Groves and Oppenheimer showed that it is possible to create an environment where there is a balance between urgency and innovation, structure and flexibility, hierarchy and egalitarianism.

Innovation is fundamentally about managing uncertainty and risk, and the more radical the innovation the higher the uncertainty to manage. Using a top-down, highly directive leadership style doesn’t work because it increases risk (one person’s judgment is more error prone for complex problems) and reduces intrinsic motivation among employees which is essential for innovative problem solving.

Despite the fact that Groves and Oppenheimer were both highly competent in their own ways, they did not push down any directive that would interfere with problem solving. Instead they did the opposite – by really listening to the people doing the work, they were able to clearly understand the inherent limitations in the project. They did several other things that led to a creative climate. For example, Oppenheimer insisted early on that scientists have full access to the compound so they could observe all aspects of the project, leading to free flow of ideas. He was also known to take good care of his people, so compensations were generous and equitable. Teams also didn’t shy away from conflicts – vigorous debates were common but they were focused on problem solving. Intentionally or intuitively, they made sure that none of the factors that harm creativity and problem solving were accidentally introduced in their management approach. By enabling the scientists and engineers, they allowed more creative solutions to emerge for the myriad of challenges that kept popping up.

Groves and Oppenheimer were successful, not by following any pre-existing playbook, but by systematically removing any barriers that came in the way of innovation.