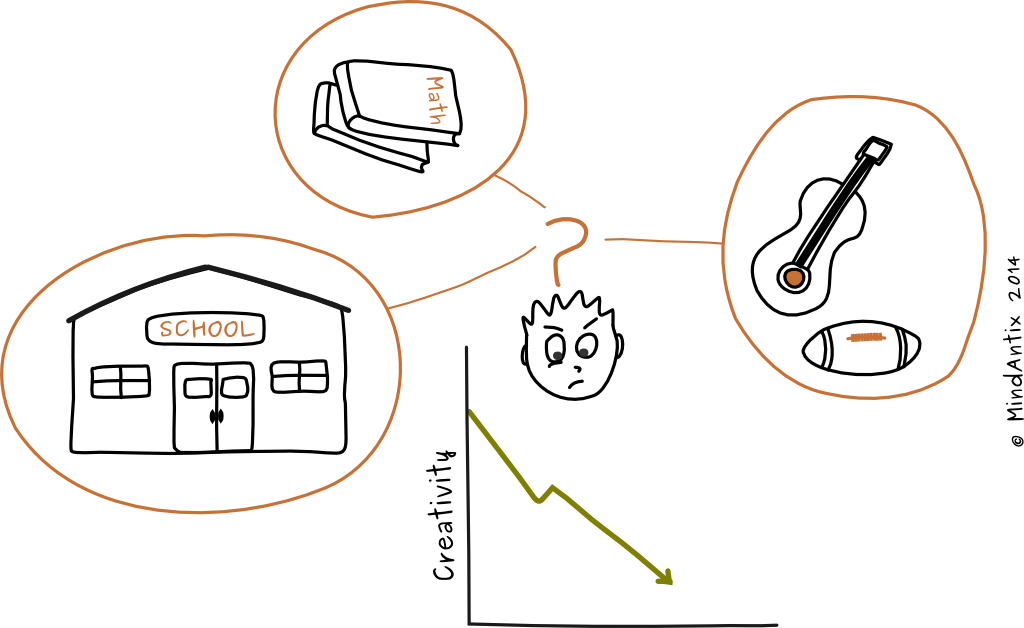

There is a growing debate in the education world about how schools are squelching creativity in our kids. Sir Ken Robinson, a leading proponent of this theory, outlines his argument of how we are “educating people out of their creative capacities” in a humorous and immensely popular TED talk. For those who haven’t seen his talk, the video is embedded at the end of this blog and I highly encourage everyone to watch it.

There are a few ways that schools shortchange our children as Sir Ken Robinson points out in his talk. The first is that our view of intelligence is still dominated by academic ability. Despite the advancement in our understanding of intelligence – that it is diverse (as proposed by psychologists like Howard Gardner and Robert Steinberg), dynamic and distinct – our educational system still focuses primarily on logical-mathematical and linguistic intelligence. Our belief in what’s important to learn leads to a hierarchy of subjects with math and languages at the top and humanities and arts at the bottom. This results in a system that discourages kids with strengths lie outside of the “top” subjects. And, this one-size-fits-all approach robs everyone of an opportunity to develop different kinds of intelligences and ways of thinking. Finally, by creating a culture where mistakes are stigmatized, schools make kids more risk-averse and less creative. Sir Robinson raises valid points in his talk but is that the whole story – are only schools responsible for undermining Creativity?

Kyung Hee Kim, a leading researcher on Creativity, analyzed creative thinking scores for K-12 students over the last few decades and found that Creativity has been declining steadily since the 1990s. This is a worrisome trend, because, as she puts it, “it stunts abilities which are supposed to mature over a lifetime.” In addition, she found out that the biggest drop in creativity, surprisingly, was for the K-3 age group, a group more influenced by home than school.

In her article, Kim outlines three factors that might be playing a role in the declining creativity trend.

-

Time to think: In our rush to provide children with enriching after school activities (ironically, to complement school’s left-brain slant), we are leaving them with less time for free play and for “reflective abstraction”. In two studies (1, 2) spanning 1981-2003, Sandra Hofferth, a professor at University of Maryland, found that discretionary time for children reduced by 14 hrs per week in that time period. In addition, structured activities are taking up an increasing portion of discretionary time leaving children with little time to think and reflect.

-

Problem Finding: Problem finding uses a different set of skills as compared to problem solving. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi makes a distinction between “presented” problems, which are formulated by others, and “discovered” problems which are self-identified. While creative solutions are often found for presented problems, major breakthroughs occur more with discovered problems. Einstein was not alone in holding this conviction when he said, “the formulation of a problem is often more essential than it’s solution.” Other studies have also shown that students show more motivation to solve self-generated problems and they come up with more creative solutions for them as compared to presented problems.

-

Collaboration: Creativity also emerges from collaborative groups. Studies have shown that other people’s ideas can be stimulating when group members actively listen to each other’s ideas. Children’s creativity can be enhanced by providing them with a receptive and encouraging environment to discuss ideas.

With so many changes in our values and lifestyle since the ‘90s it will be hard to narrow down all the factors causing a fall in creativity, so this debate is here to stay. But what can we all do in the meantime? I believe that we should encourage children to think in many different ways whenever they can – adopt different perspectives, challenge assumptions, ask “what-if?”, and find new kinds of problems (real or hypothetical situations) to think about at school and at home. Ask “why?” five times to get to the root of any problem and to find more creative solutions. And then ask “why not?”. Learning to think and ask different questions not only helps in acquiring deeper insights but also reveals more creative solutions. “The uncreative mind can spot wrong answers,” said Sir Antony Jones, co-author of the famous British comedies Yes Minister and Yes, Prime Minister, “but it takes a very creative mind to spot wrong questions.”