A few years ago, a research study to understand the impact of autism conditions on creativity found an unexpected result. Researchers found that while people on the autism spectrum come up with fewer responses to divergent thinking problems (e.g. different ways to use a paper clip), the responses are more original than the neurotypical population.

The most common advice given for productive brainstorming — to come up with lots of ideas which increases the chance of coming up with original ideas — doesn’t seem very relevant for this group. It appears that some of the characteristics of the autism conditions confer an advantage when it comes to creative thinking. As the researchers found, “…when fluency was statistically controlled for, people with high levels of autistic traits were more likely to produce unusual novel responses. This would be a potential cognitive advantage for creative problem solving.”

So why does this happen?

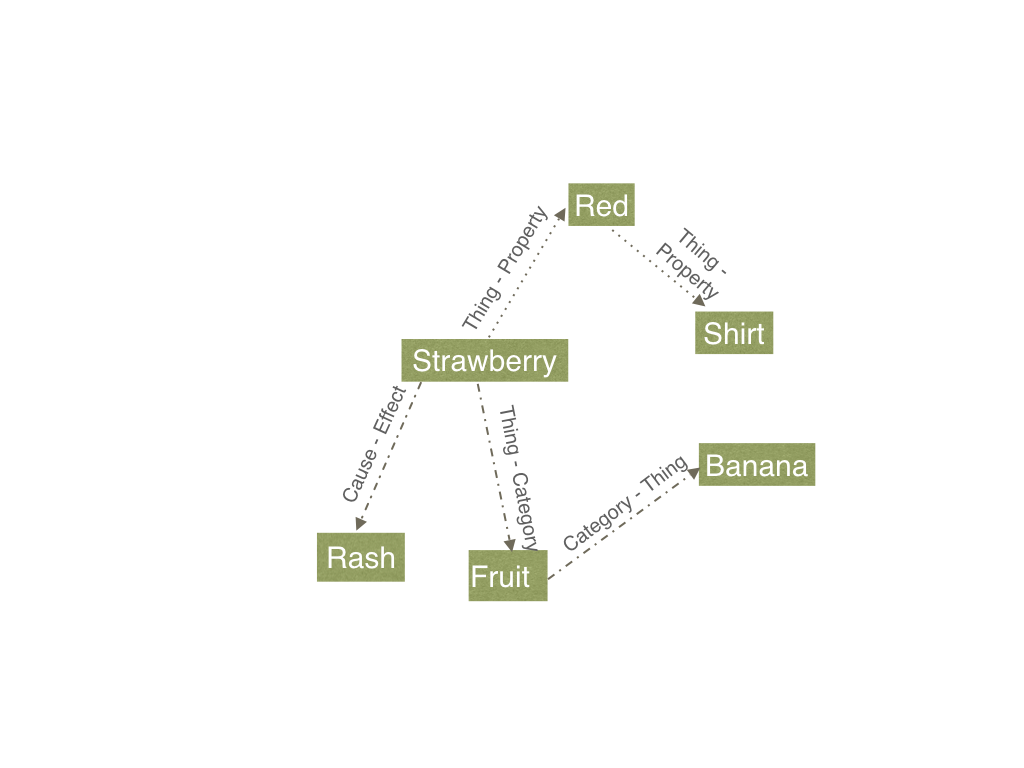

One possible explanation lies in how we store and process information. Our brain is an associative engine, where all the concepts we know are stored as nodes interconnected through links. These links can be of different types and strengths. When we think of one idea, the next thought most likely to pop into our head is the idea that has the strongest connection to the first idea. For example, someone allergic to strawberries might have a strong ‘cause-effect’ link between “strawberry” and “rash”. Everytime they hear the word “strawberry” they might immediately think of a rash.

For most people, thinking of a concept leads to hopping from one node to the next strongest connected node in one train of thought. This phenomenon, also called falling into an ‘associative-rut’, is what leads to the initial set of fast, not-so-original ideas during brainstorming.

However, for those with autism spectrum conditions (ASC) it is possible that there isn’t one strong associative path to go down, and instead other paths are equally visible. In proposing the hyper-systemizing theory of autism, researchers noted that what appears as slow processing to an outsider might be due to the massive amounts of information being processed. An interviewee with Asperger’s syndrome explained his thinking as:

“I see all information in terms of links. All information has a link to something and I pay attention to these links. If I am asked a question in an exam I have great difficulty in completing my answer within the allocated 45 min for that essay, because every fact I include has thousands of links to other facts, and I feel my answer would be incorrect if I didn’t report all of the linked facts. The examiner thinks he or she has set a nice circumscribed question to answer, but for someone with autism or Asperger’s syndrome, no topic is circumscribed. There is ever more detail with ever more interesting links between the details.”

The above description also provides a clue on why people with ASC come up with fewer but more original ideas. They ‘see’ more information which increases processing speed, but at the same time this ability makes it easier to avoid going down the routine path.

In a similar vein, a study on verbal creativity found that people ASC generate more creative metaphors compared to neurotypical populations (e.g. “Feeling worthless is like offering a salad to South Americans”), while comprehension of conventional metaphors was similar between the two groups. The authors conclude, “Our results suggest that adults with ASD can create unique verbal associations that are not restricted to previous knowledge, thus pointing to unique verbal creativity in ASD.”

ASC needs to be viewed more as a cognitive style, as opposed to a deficit. These differences in how information is processed has demonstrated several advantages, including superior ability in certain aspects of creative thinking.