With the terrorist attack of 9/11, US airlines were suddenly faced with a black swan crisis. The entire airspaces of US and Canada were shut down for 48 hours by federal order, and when civilian air traffic resumed it was significantly limited. Despite billions of dollars in federal assistance to cover for lost revenue the airline industry continued to lose millions of dollars per day. To curb this loss, major airlines cut their flights by an average of 20% and laid off an average of 16% of their workforce.

Two airlines – Southwest and US Airways – that both focused on short-haul flights and therefore faced disproportionately higher travel disruptions, adopted very different strategies during the crisis. US Airways had the highest level of layoffs in the industry at 24%, while Southwest went the other extreme and did not lay off any employees. Four years after the crisis event, their performance couldn’t be more different. Southwest Airlines had the fastest performance recovery and regained 92% of its stock price pre-911 while US Airways could only achieve 23%.

So why did Southwest rebound back so strongly after the crisis?

The key, as researchers discovered, was organizational resilience. Southwest by retaining all their employees had the right combination of resources to find creative ways to reduce costs and improve productivity. When organizations lay off people purely by numbers, they not only lose individual expertise, they also lose intelligence that emerges from the relational networks that employees were part of. These networks are hard to rebuild even when they hire new people at a later time.

One way to think about this is that people build both strong and weak relationships at work. Within their immediate groups they go through the forming, storming and norming, to finally reach the performing phase. In the process they build a deeper understanding of each other and their respective strengths. Beyond their current and past teams, they also build weaker relationships with others in the company over time. So they might know that Joe over in marketing has great relationships with client companies or Jane in accounting is a spreadsheet wizard. In a crisis situation these insights and information end up being especially valuable, as people reorganize themselves and try creative approaches to meet the challenge. Disrupting these relationships harms the ability to innovate and problem solve in an emergency. As the research paper explains, “Paradoxically, a common organizational response to crisis–i.e., layoffs–tends to undermine the very relationships that help organizations cope during periods of crisis.”

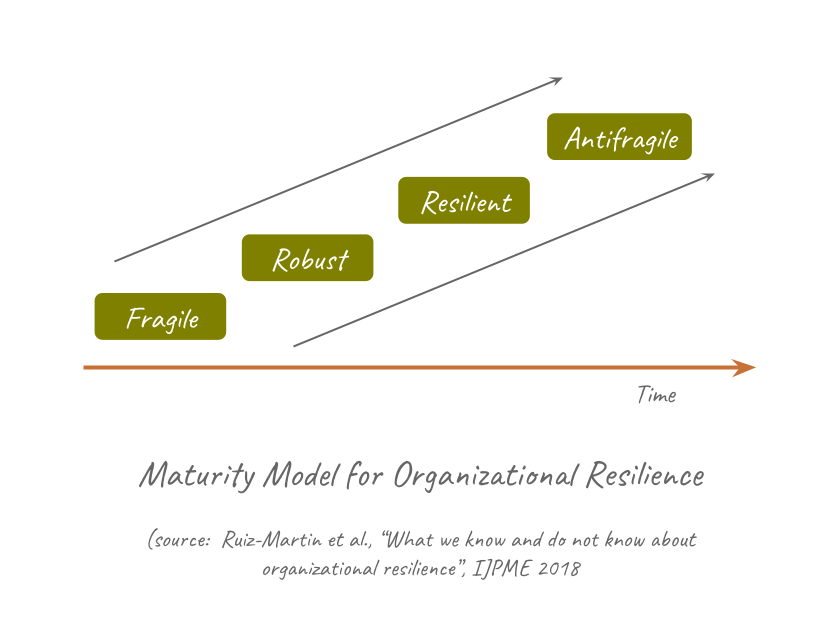

Organizational resilience is the ability to bounce back from a crisis to achieve a new stable point. The ability to withstand disturbances can be viewed as a spectrum with fragile at one end and antifragile at another. A fragile system is one that is unable to handle the challenge, much like US Airways that eventually went through two bankruptcies before finally merging with American Airlines. The next step up is a robust system that can absorb a set of known disturbances and comes back to the original stable point. A resilient system goes a step further – it can absorb unknown stresses by landing at a different desirable point of stability. Finally, an antifragile system is one that bounces back to a new stable point which is better than the previous one. In other words, an antifragile system takes the chaos created by the crisis and emerges stronger than before.

Resilient and antifragile systems allow one to thrive in uncertain conditions, which is becoming increasingly important. As companies face more volatile environments with frequent natural, geopolitical and other disruptions, building organizational resilience is becoming essential.

So how does one consciously build a resilient and antifragile organization? There are three main areas to consider – creative thinking, group coordination and organizational mindset.

Creative Thinking

An unexpected crisis requires new ways of thinking and doing things since the crisis brings a new environment and constraints with it. So, the foremost principle is bricolage – the ability to improvise and find creative solutions. Organizations become less vulnerable if they are able to recombine existing resources, processes and expertise to create novel solutions. Ducheck, who researches organizational resilience, captured this essence with “What first sounds counterintuitive—to improvise in already chaotic situations—can help to prevent catastrophe.”

However, you can’t turn on a faucet and expect creativity to flow if the underlying plumbing was never installed. Creativity has to be in the company’s DNA – a core part of its culture. Without a creative culture, companies might occasionally get lucky with dealing effectively with a crisis, but it’s not a long-term sustainable solution. Instead what organizations need to build is strategic resilience – the capacity to continuously anticipate and adjust practices in order to meet incoming challenges. And one way to do that is through well-integrated innovation programs that tap employee creativity. Such programs surface ideas from frontline employees that are valuable but often ignored. Taleb, who coined the term antifragility, goes a step further with, “If about everything top-down fragilizes and blocks antifragility and growth, everything bottom-up thrives under the right amount of stress and disorder.”

In their HBR article, The Quest for Resilience, Hamel and Välikangas point out two mistakes that companies often make when they build employee innovation programs.

First, companies often focus on a few big bets instead of funding many small bets. The problem with that approach is many high potential ideas get stymied early on, so companies don’t capture the full benefits of employee innovation. Additionally, the lack of variety in ideas makes companies less resilient in the long-run. Equally importantly, big bets leave rank and file employees out of the innovation cycle depriving them of opportunities to practice creative thinking. The authors recommend that “a reasonably large company or business unit—having $5 billion to $10 billion in revenues, say— should generate at least 100 groundbreaking experiments every year, with each one absorbing between $10,000 and $20,000 in first-stage investment funds.”

Second, when companies do introduce formal innovation programs they create innovation ghettos, separate from the regular day to day work. For example, hackathons or incubators where people work on ideas (sometimes for a very short time) that are outside the core and don’t really change the company bottom line. What companies need, instead, is an innovation pipeline that is integral to the work people are doing like what Whirlpool is doing. In the 1990s, Whirlpool made innovation a core competency and recruited a big part of their workforce to search for breakthrough ideas. By training people and creating tools to track innovative ideas, they institutionalized the process of innovation for their company.

Collaboration

To successfully deal with crises, teams often have to self-organize into ad-hoc networks that pull in the right set of expertise and skills. Organizations that allow easy collaborations across groups on a regular basis are more adaptable to challenges than organizations that are siloed. Collaborations across immediate groups or divisions, expand resources that can be used and improve the capacity to respond to the event.

But getting the right people together is not enough to solve complex problems if people lack the cognitive and interpersonal skills to take each others’ ideas and synthesize a novel solution from them. Breakthrough ideas emerge from egalitarian groups where people actively listen to each other’s ideas and consciously make an effort to integrate different perspectives.

Reducing bureaucracy towards inter-group collaboration and building the right teaming skills (both cognitive and social-emotional) make organizations flexible and nimble when unexpected events shake things up.

Mindset

Most people assume that resilience is fueled by optimism. However, optimism by itself can be dangerous – it leads to toxic positivity, hubris and blind spots. Instead, resilient organizations display hopefulness which can be described as simultaneously holding two beliefs – that their systems are not infallible and that they have the competency to find solutions when things do fail. Vagus and Sutcliff define this hope as “a confidence grounded in a realistic appraisal of the challenges in one’s environment and one’s capabilities for navigating around them.”

This mindset at the organizational level is driven by leaders and filters down to rest. It requires a culture of humility that takes its prior successes lightly. It requires people to continually question their products and environment, and proactively address things before they become issues. Fragile organizations, on the other hand, place a low priority on such proactive work (e.g. “if it’s not broken don’t fix it” or “convince me this is an issue”).

Building the right mindset within an organization goes hand in hand with building creative thinking and collaborative skills. People need to personally experience their collective ability to manage disruptions, without which leadership’s assertion of internal capability will sound hollow.

Conclusion

No one could have predicted the Covid19 pandemic and the disruption it would create a few years ago. As the world continues to get more connected and more complex, unexpected threats continue to rise. While we can’t predict a specific threat, we can expect to face some crisis in the near future. Whether a company crumbles under the pressure of unanticipated threats or emerges stronger than before depends on its level of organizational resilience. Unfortunately, many companies inadvertently do things that reduce their resilience – they undervalue people’s creativity and relationships, they push down directives from the top instead of encouraging bottom-up problem solving, they reduce communication which thwarts collaboration and they fail to deploy the right kind of resources. Resilient organizations flip traditional organizational theory on its head and deploy cognitive, relational and financial resources instead of restricting them. They create cultures where employee creativity is valued, because unexpected threats require unexpected solutions. They recognize that much like marathons, organizational resilience depends on training before the crisis event. As Herb Kelleher, the founder of Southwest Airlines, said, “If you create an environment where the people truly participate, you don’t need control. They know what needs to be done and they do it.“