One of the most common divergent thinking tasks is the Alternate Uses (AU) Task where you take an everyday object and think of different uses it can be put to. For example, a cup could be used as a flower vase or as a hat or even as a toy. Designed by psychologist J.P. Guilford in 1967, the Alternative Uses Task is used as a standard creativity task to evaluate fluency, flexibility, originality and elaboration of responses. But coming up with creative ideas is tricky because most people find it hard to move beyond their first strong associations. So, how can you jumpstart your brain into thinking of novel ideas?

In a study done on the Alternate Uses Task, researchers found that participants arrived at more novel responses after listing more obvious ones (typically after 10 or more responses). In a different study on divergent thinking strategies, researchers analyzed how participants responded to alternate uses and discovered some interesting patterns. They found four underlying mechanisms that people use to trigger new ideas: Memory Use (pull pre-known responses from memory), Property Use (pick a property and search for functions using that property), Broad Use (review the object against a broad use like “transport”), and Disassembly Use (pick a component of the object and find a use for it).

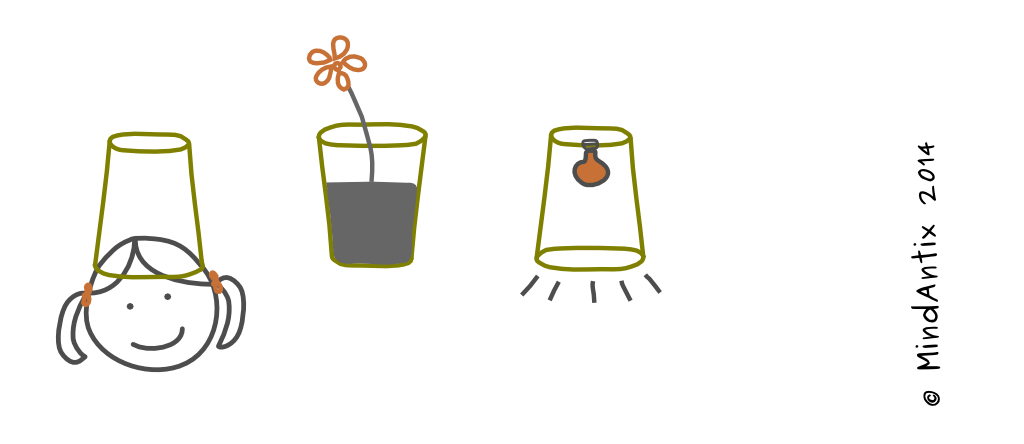

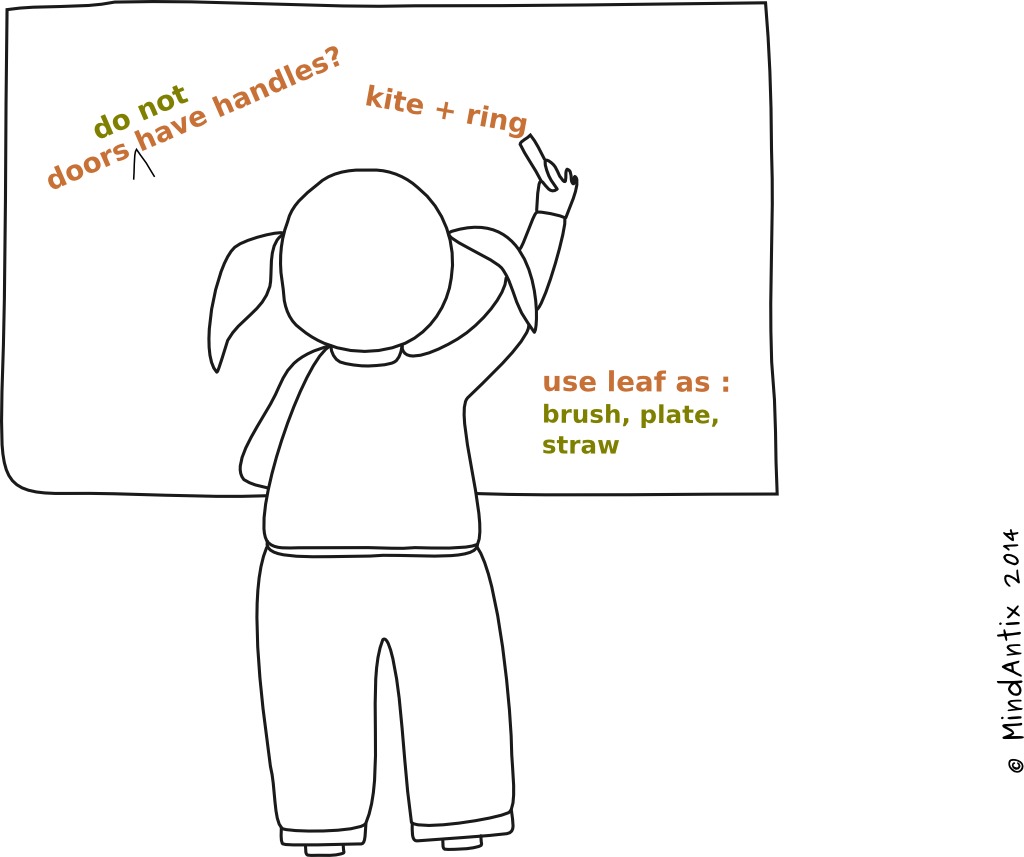

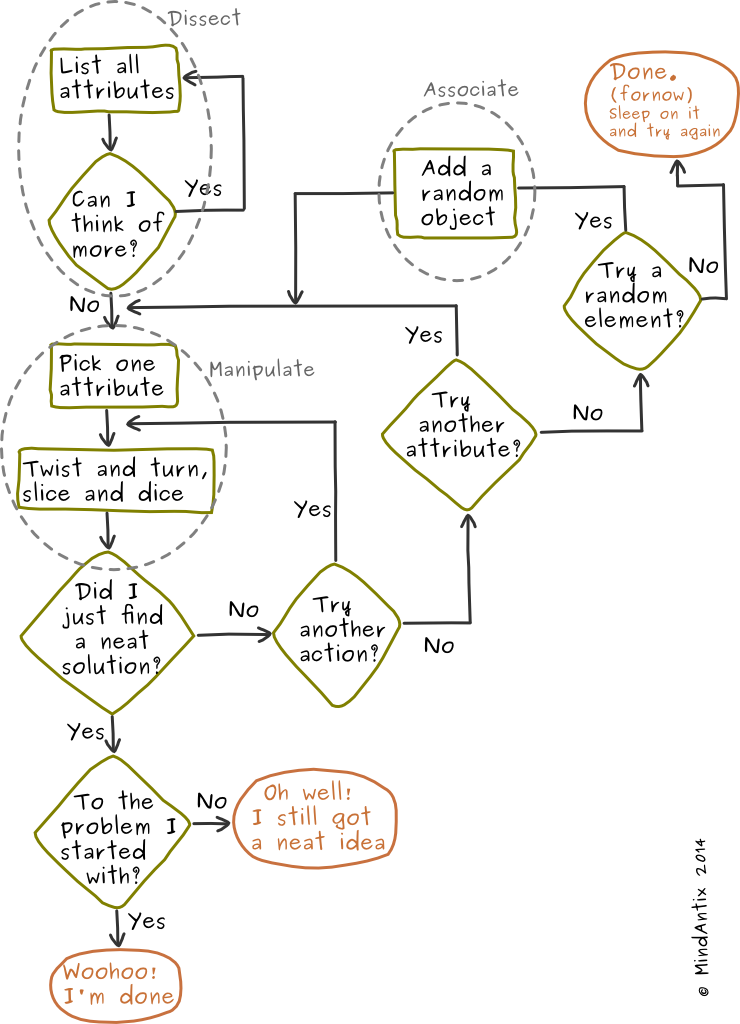

We can apply the three step process for creative thinking to our cup example to discover novel ideas in a more structured way. As the first step, we dissect the object into its properties (glass, metal, round), function (drink liquids from), or assumptions (hold liquids, kept open side up). In the next step, we can try and change one or more of these properties and then see if the resulting object could be used for something else. For instance,

- instead of holding liquids, it could hold solids (vase, piggy bank, pencil holder).

- if it was inverted it could be used as hat or a lamp shade.

- if it was made of paper, you could cut the circle at the bottom and use that as a coin.

Once you dissect in many dimensions, you get many more starting points to modify things and come up with neat uses. In fact, the responses deemed most creative (property use) in the divergent thinking study fit neatly into the dissect and manipulate approach. You could also include the third step, associate, to increase your idea fluency. For example if you attach a string and a ball to the cup you could make a new kind of paddle ball or kendama.

So, when you attempt the “Many Uses” brainteasers (a loosely constrained version of Alternate Uses) on MindAntix, or similar problems elsewhere, try to dissect and change things to trigger more unusual connections. And remember, your best ideas will likely come in the second wave – after the more obvious ones.