Imagine this. You’re part of a cross-functional task force assigned to design a new customer service experience. The kickoff meeting was promising and everyone looked excited about the project. But fast forward three weeks, and the group is spiraling. Deadlines are slipping and the frustration is mounting. What once looked like a dream team now feels like a dysfunctional mess.

Sound familiar?

Most of us have experienced the kind of group work that leaves us exhausted and disappointed. Despite the best intentions, placing people together on a joint project does not automatically result in collaboration. In fact, some groups can become so ineffective that they perform worse than individuals working alone.

The truth is that teamwork doesn’t happen by accident. It has to be designed.

Below, we unpack the five essential elements that transform individuals into high-performing, cooperative groups.

The 5 Dimensions of Effective Group Cooperation

1. Sink or Swim Together

The foundation of effective teamwork begins with a mindset shift: “I can’t win unless we all win.” This is the essence of positive interdependence. Team members must believe their success is tied to the success of others. This interdependence can come in two forms:

- Outcome interdependence, where rewards and goals are shared like bonuses tied to team performance.

- Means interdependence, where members rely on one another for roles, tasks, or resources.

When people see their unique contribution as indispensable to the team’s success, they engage more fully. Conversely, if individuals perceive their effort as irrelevant, they’re likely to disengage. A well-structured group ensures that every member is both necessary and valued.

2. No Free Riders

Accountability prevents what psychologists call “social loafing”—when some members slack off, assuming others will pick up the slack. Effective groups balance individual accountability with group accountability.

- Individual accountability ensures each person is responsible for a tangible piece of the outcome.

- Group accountability holds the entire team responsible for the collective result.

By making both individual and team contributions visible—through regular check-ins, peer feedback, and shared rubrics—groups create a culture of fairness and motivation.

3. Promotive Interaction

Teams aren’t just about dividing tasks to complete individually but about advancing shared thinking. The heart of collaboration is promotive interaction—when group members actively support, encourage, and challenge one another in real time to improve performance and understanding.

But not all interaction is promotive. Side chatter, passive agreement, or one person dominating the discussion can stall progress. What effective teams practice is idea generosity—they build on each other’s contributions rather than blocking or bypassing them. Approaches like “yes-and” thinking from improv or plussing from Pixar are useful tools in building productive and healthy interactions.

In promotive interaction, the conversation becomes a kind of collaborative scaffolding. Each person’s input provides a platform for the next, creating an upward spiral of insight and innovation. As one team member adds a piece, others connect, refine, or extend it, until the final outcome is richer than anything any one person could have imagined alone.

4. Social Skills

Effective collaboration isn’t instinctive. You can’t expect a group of strangers to work together seamlessly just by telling them to “be a team.”

At the heart of effective cooperation is a set of interpersonal and group skills that must be learned, honed, and deliberately applied. These include:

- Building trust and rapport

- Communicating clearly and without ambiguity

- Offering support and constructive feedback

- Navigating power dynamics and decision-making

- Managing and resolving conflict productively

And it’s that last point, conflict, that often separates good teams from great ones.

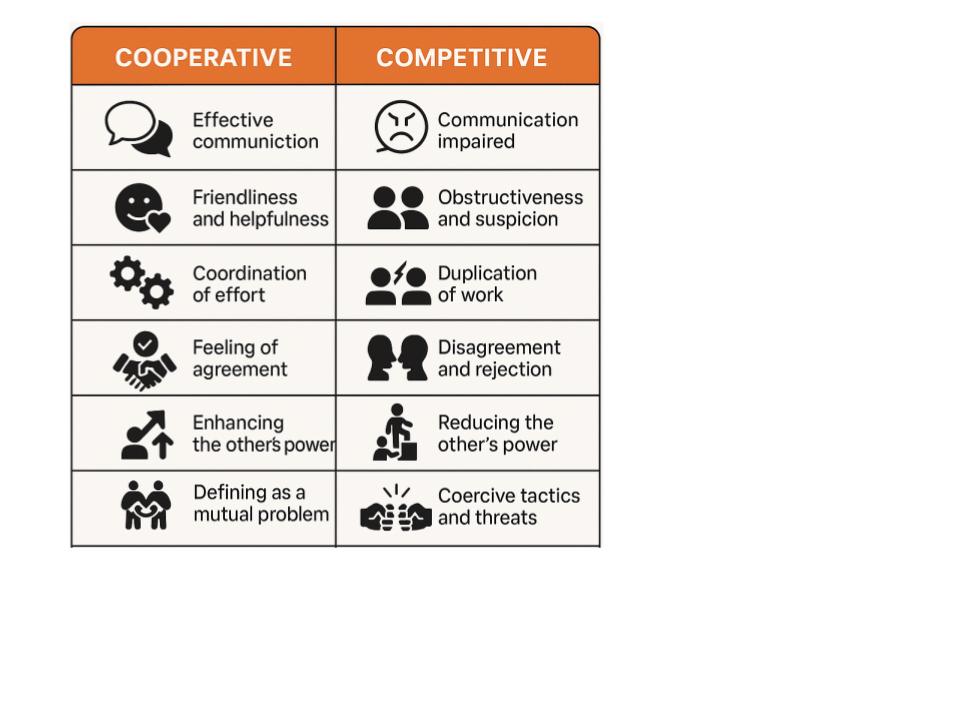

In high-functioning teams, conflict isn’t something to be avoided but something to be engaged with skill. Differences in perspective are seen not as obstacles but as opportunities for deeper insight. This is where constructive conflict becomes essential, and where the earlier skills truly come into play.

Take, for instance, the technique of structured controversy. Rather than skimming over disagreement, team members are encouraged to:

- Prepare the best case possible for their assigned point of view

- Present and advocate for it respectfully

- Critically examine opposing ideas

- Drop all advocacy and look at the issue from all sides

- Arrive at a consensus based on reasoned judgment, not politics or personality

This process not only leads to better decisions, it also cultivates psychological safety, creativity, and mutual respect.

To engage in this kind of conflict constructively, groups need more than good intentions. They need the social and group skills to keep things productive when the stakes are high. That includes:

- Listening to understand, not just to respond

- Asking clarifying questions rather than making assumptions

- Separating ideas from identity, so critique isn’t taken as personal attack

- Being flexible with ego and open to being wrong

These soft skills become especially important in complex, ambiguous, or high-pressure environments. The teams that thrive are not those that avoid friction, but those that know how to transform friction into forward motion.

5. Group Reflection

Great teams become highly productive by taking time to reflect regularly. Through group processing, they periodically pause to ask:

- What’s working well?

- Where are we getting stuck?

- What should we do differently next time?

These debrief moments might feel like a luxury in fast-paced environments, but they’re actually a necessity. They surface hidden tensions, refine team norms, and reinforce habits that promote continuous improvement.

Think of it as a team “mirror”—holding up a reflection so the group can self-correct, adapt, and grow.

What Leaders Can Do: 3 Guiding Principles

Creating a team that thrives is not about charisma, luck, or personality but about intentional design. Here are three guiding principles leaders can use to build truly collaborative groups:

1. Design for Interdependence and Accountability

Effective teams don’t just share goals—they depend on each other to reach them. Structure work so that every member’s contribution is distinct and necessary. Assign differentiated roles, create shared metrics for group success, and ensure individual efforts are visible and valued.

When team members know they are responsible to each other, and not just to the boss, accountability becomes intrinsic.

Ask yourself: “What makes each member essential to the outcome?”

2. Shape the Social Architecture

Cooperation isn’t a personality trait—it requires practice. And it starts with group norms. As a leader, you’re the architect of that culture. Set clear expectations for how your team communicates, gives feedback, navigates disagreement, and makes decisions. Model the behaviors you want to see—curiosity, humility, and “yes-and” thinking.

Equip your team with the tools of collaboration: listening skills, facilitation techniques, and constructive conflict strategies. These are the scaffolding of effective group work.

Ask yourself: “Have we made cooperation easy or left it to chance?”

3. Build in Time to Reflect and Learn

The most effective teams don’t just do the work—they learn how to do the work better. Create regular spaces for group reflection: what’s working, what’s not, and how to improve. These debriefs don’t need to be long but they do need to be honest.

Reflection transforms teams from task-executors into adaptive systems. It reinforces psychological safety, surfaces process inefficiencies, and strengthens shared ownership.

Ask yourself: “Where do we pause to learn from how we work?”

Final Thoughts

Next time you find yourself in a struggling team, remember this: cooperation isn’t chemistry. It’s architecture.

Effective group work doesn’t magically happen just because people like each other, or because they share a task. It happens because the invisible structures of interdependence, accountability, promotive interactions, social skills, and reflection have been built with intention.

When those elements are in place, the same group that once floundered can rise to produce work that no individual could have achieved alone.