If you were to pick a team to design your next product, who would you choose – a team of professional product designers or a group of improvisational comedians? If you took the first option, you might want to think again. Barry Kudrowitz, an assistant professor and director of product design at University of Minnesota, conducted this exact experiment as part of his Ph.D. thesis at MIT.

In his study of 84 participants, he found that improvisational comedians produce 20% more product ideas and 25% more creative ideas than professional product designers. He also found that improvisational training can increase idea output for subsequent product brainstorming. While this sounds improbable, it makes sense when you consider that both creative thinking and improvisation rely on making non-obvious connections between unrelated concepts. As Barry explains, “The more I looked at humor studies, I found a lot more connections between what makes something funny and what makes something innovative.”

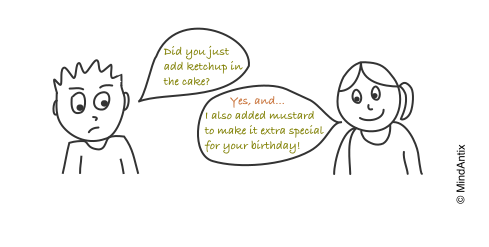

One of the fundamental tenets of improvisation is the concept of “Yes-And”, or the idea that you never contradict your partner and instead build on what he or she just said. For example, suppose someone says, “It’s so cold in here,” and you respond with “Seems fine to me…”, the scene starts to stall. If instead you said, “I told you it wasn’t a good idea to hide in the refrigerator,” you could start to build an interesting scene. At a fundamental level, “Yes-And” is all about forcing yourself to find interesting connections, or building associative thinking, a core creativity technique.

In our creativity and invention classes, we routinely use improvisational games as warm-up exercises to get creative juices flowing. Here are three of our favorite improv games that are not only fun, but they also build specific creative thinking patterns.

What Are You Doing?

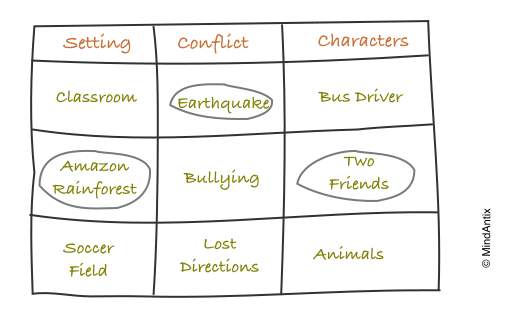

This is an improv game that that engages both the critical and creative sides of the brain and builds associative thinking. Two people are invited onstage and given two letters of the alphabet (e.g. A and B). One player asks the other, “What are you doing?” and other player answers with an action phrase like “Arguing Baskets” and proceeds to act it out no matter how silly it appears. Then the players trade places and repeat the game.

Minion Game

This game is based on the Alternate Uses Task and is played in small groups. The group is given a simple object (like a pencil) and everyone in the group pretends to be minions who have just come across this human object. They take turns interpreting how that object might be used by humans. The trick is to not suggest a way that it is already used, like in this case for writing but for something completely different like using it as chopsticks.

Fortunately/Unfortunately

This is a fun game that builds ability to reverse direction and view things from a different perspective. This game can be played by the whole group at the same time, and everyone takes turns telling the good news and bad news in a story. The first person is given a prompt (e.g “I took out the assignment from my bag”) and he has to say a sentence that begins with the word “Fortunately” (e.g. “Fortunately, it was a very simple assignment”). The next person has to come up with the bad news and start the sentence with “Unfortunately” (e.g. “Unfortunately, it had been due the last week”) and so on.

So the next time you are running out of steam in a brainstorming session, take a break and try an improvisation game or two!