As we start the new year, events and challenges from the last few years are continuing to shape our lives and the way we do business. Companies have had to make peace with remote/hybrid work being the new normal, adjust their cost structures to deal with economic uncertainties and redesign employee experiences to keep people engaged – all while fighting to stay ahead of the competition. If we needed an example of what a VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous) world would look like, the last few years have clearly shown us that.

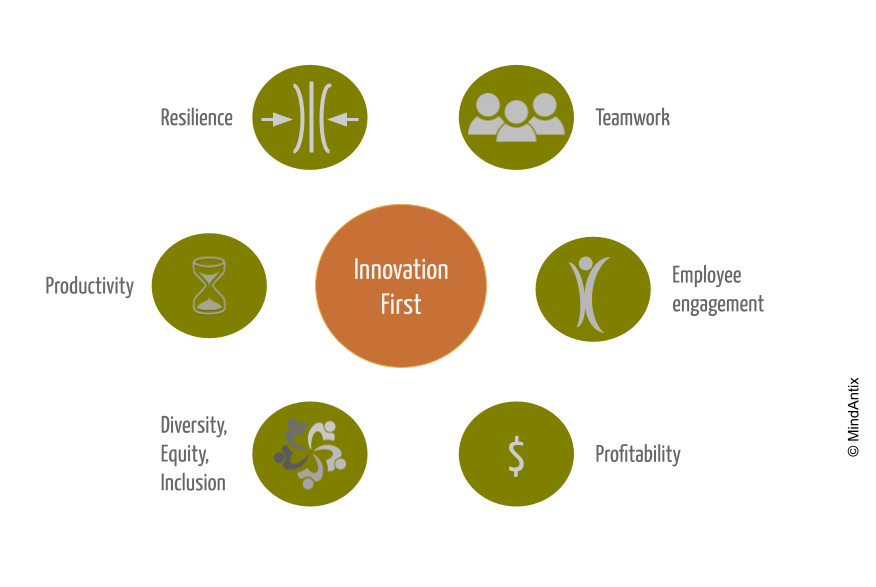

How can companies successfully navigate such challenges going forward? We believe that the best way forward is to focus on innovation, first and foremost. By doing so, companies create the right kind of people-oriented cultures that not only boost revenue, but also improve other metrics like DEI or engagement. When viewed through the lens of innovation, cognitive-social-emotional skills like empathy or active listening take on a different flavor which make them far more effective in the workplace.

Three trends show why an innovation-first strategy can be beneficial to organizations.

Artificial Intelligence

ChatGPT showed that AI is advanced enough to do better than humans at certain tasks – even those that are more cognitively demanding tasks like writing essays or code. Let’s drill down a bit into one of the best paying jobs currently – software development. Using AI to help with coding is significantly improving developer productivity. Tasks that took several hours earlier, now can be done in a few minutes with a quality that is at par with the best programmers. That creates new implications for technology-focused companies.

Companies no longer need to hire as many people to do the work they need. Well funded companies spend tons of money recruiting talent from the most reputable colleges. With AI in the picture, this approach will no longer provide them with competitive advantage over smaller companies or scrappy startups who don’t have the resources to go after top talent in the same way. With AI that offloads most of the coding tasks, the difference between a talented developer and a mediocre one reduces sharply.

Competitive advantage will shift to abilities that AI can’t handle well, creative thinking being an obvious area. Creativity requires the production of novel responses, which by definition implies the lack of existing data for algorithms to learn from. This is not to say that AI can’t do limited forms of incremental creativity, but they tend to be more “within-the-box” as opposed to more transformational “out-of-box” creativity. In other words, AI can rearrange existing content in new ways which may or may not turn out to be creative, but it can’t really synthesize new concepts.

We recently tested OpenAI’s ChatGPT for several different creative prompts and our analysis shows that ChatGPT’s creativity is nowhere close to that of humans, including elementary aged children. It lacks the fundamental ability to do abstract thinking, so when posed with a challenge to invent something from two random objects, it tends to follow the simplest strategy of putting the two objects together. Or when asked to generate alternate endings to stories given a twist, it simply bails out.

The obvious implication of the rise of AI, is that companies need to build their creative capacity in order to stay competitive. Companies that prioritize building creative thinking skills (like associative or reverse thinking), creating channels to harness employee innovation and most importantly foster an innovation-focused culture will emerge as the leaders of the next wave.

Global Threats

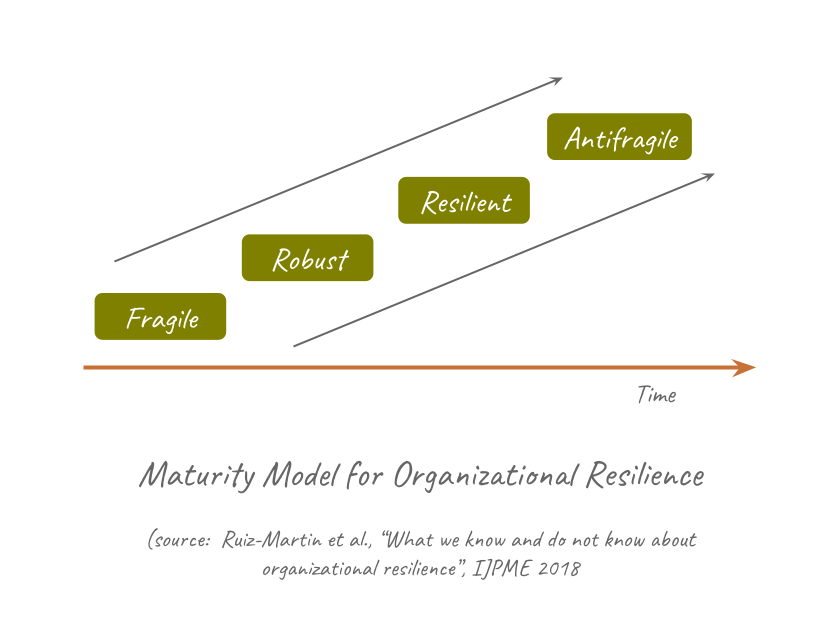

Covid19 showed the extent to which a global threat can impact lives of people all over the world. With the world being more connected and more interdependent, a local event can have major consequences. Just in the last few years, companies have had to deal not only with the pandemic and its consequences, but also geopolitical issues like wars, unforeseen natural disasters and economic recessions. Such global threats are only expected to become more frequent. Needless to say, companies that can respond to such threats in a flexible and agile manner have a much greater chance of survival.

However, the ability to be flexible and respond to changing environments in real time requires the ability to improvise and find novel solutions, to reconfigure existing resources and capabilities in new ways to solve problems, to collaborate in an open-minded way with others, to iterate when things don’t go as planned. In short, it requires the full arsenal of creative thinking capabilities deployed towards the crisis at hand. This ability to be innovative in the face of threats builds organizational resilience which significantly improves survival odds for any organization.

To build a resilient organization, innovation has to become part of the company’s DNA. Building a culture of innovation involves deliberately building core cognitive capabilities, allowing ad-hoc collaborations to take place without unnecessary friction and creating formal structures for capturing employee creativity.

Management Complexity

Managing a large workforce today is complex with many initiatives like employee engagement, talent retention and DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) taking up valuable time and energy. However, when organizations look at these as separated, isolated aspects they can inadvertently create conflicting processes and norms. This affects not just leaders but also employees, who feel like they are being pulled in different directions while having to maintain high levels of productivity.

One possible solution is to view such initiatives through the lens of innovation, which is the primary goal for any company, and identify ways to streamline and simplify. As an example, we conducted a study recently to understand the impact of gender bias on innovation within the technology industry. We found that by adopting a few universal strategies, like enhanced group decision making processes, companies can improve overall innovation while reducing the impact of bias. The advantage of using innovation as a means to reduce bias is that it removes the salience of gender or race. One of the key reasons diversity programs are ineffective is that they bring race or gender sharply into focus, thereby reinforcing the stereotype even more. Ironically, the most effective diversity programs aren’t specifically designed for diversity. This is not to say that all DEI initiatives can be made redundant, but by finding synergies it is possible to do more with less.

Using An Innovation-First Approach

An Innovation-First approach is a way to streamline and consolidate multiple goals in a way that optimizes the primary goal of innovation and productivity. It’s a way to refactor company cultures to remove redundant, conflicting or ineffective processes and orient the entire organization towards a common purpose. As a result, companies create healthier organizations where both employee engagement and profitability is high.

For the last several decades companies have focused narrowly on employee productivity, which works for linear and predictable workloads. However, with the current trends in AI, automation and globalization, this is no longer enough. Companies that can successfully adopt innovation will gain a significant competitive advantage over their rivals.